The Oil Machine in Torrington, North Devon

Cathy Slaughter is explaining a little about XR North Devon as people slowly drift into the foyer of The Plough Arts Centre in Torrington, North Devon.

“There’s a good group of really active members and of course many more who are signed up on the Facebook page. We had a great turn out at the Dirty Water Protest in Barnstaple two weeks ago.”

There is a hubbub in the area around the ticket sales booth and the bar, as the audience builds for a screening of The Oil Machine.

The Plough Centre faces onto Fore Street at the heart of Torrington, on land that gently slopes to the river beyond the houses. Down to the Torridge winding its way to the Severn Sea. I had travelled to the screening in a Go Ahead bus from Exeter, rattling into the Devon dusk. An orange sun set over the purple massif of Dartmoor to the west as the road followed the rivers Exe and then the Creedy, flowing through through Newton St Cyres and Crediton. Near Down St Mary the road came to its’ highest point and the bus rumbled into the catchment of the Taw. Not long after we crossed another watershed and entered the valley of the Torridge.

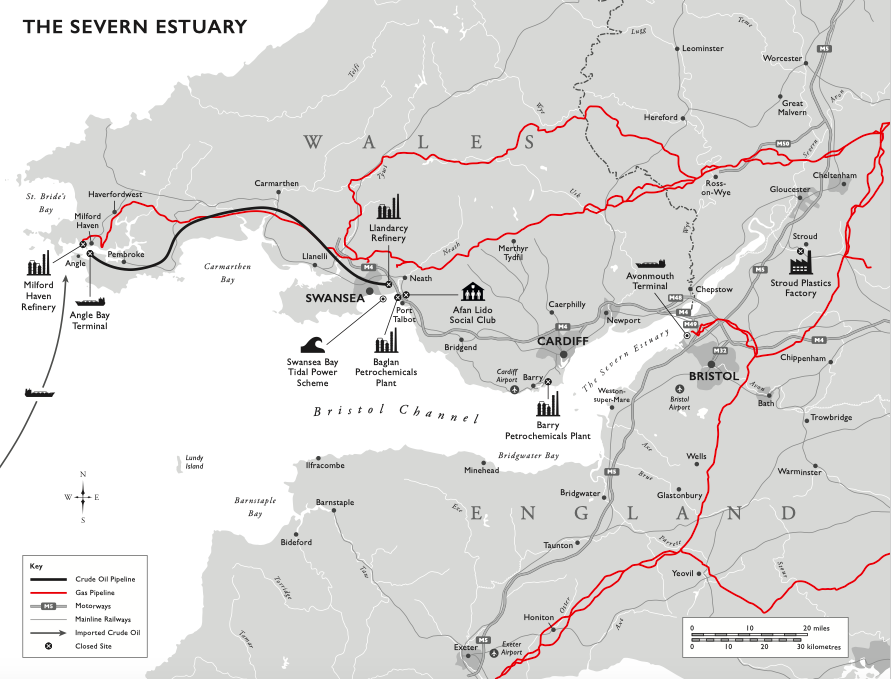

These two rivers, the Torridge and the Taw, are twin sisters of North Devon. They unite close to Barnstaple and flow into the Severn Sea – perhaps better known as the Bristol Channel. Far across its breadth lies South Wales and the remains of the coal and oil industry that we explored in Crude Britannia. North Devon and South Wales can seem different worlds, but they are united by this common sea and a shared responsibility for all that spills into it.

As Cathy speaks I find myself at first surprised that a demonstration against water pollution was the highlight of the group’s recent work. In my naivety I had thought of XR as being intent on bringing change in the national government’s response to climate chaos. And those groups that have grown from XR as having specific focuses on battling carbon which their names describe – Insulate Britain and Just Stop Oil.

The Dirty Water Protest, organised by XR North Devon, that Cathy talks of was held on Castle Green in Barnstaple on 24th January. A big crowd, 170 strong, gathered, with folks from twenty-seven groups including North Devon Green Party, Surfers Against Sewage, and Torridge Action Group (Save the River Torridge). All were united in their outrage at the state of the water and the failure of the local politicians to protect it, in particular Selaine Saxby (Conservative MP for North Devon) and Geoffrey Cox (Conservative MP for Torridge & West Devon) The protest was followed by another wave, led by XR North Devon, in Bideford and Barnstaple during March.

The level of anger is not surprising, for this is a land of constantly running water, of ditches, rivers and the wide wide estuary embracing Barnstaple Bay. This is a land whose story is sold to tourists not as a place of cathedrals and castles, but of rushing streams and otters. For this is the setting of Henry Williamson’s classic book ‘Tarka the Otter’ and its companion piece ‘Salar the Salmon’. The Tarka Trail foot and cycle path winds through the valleys of the Taw and Torridge. The sound of water fills the ears in villages and towns, except where it is drowned out by the rumble of engines and the swoosh of tyres on tarmac.

There is a battle between oil and water. It rages here as it does in every river catchment. The Go Ahead bus probably drips fuel onto the tarmac when it stops at the lights coming into Torrington. The tractors doubtless leak diesel on the roads as they pass through the town. However minute each spillage is, it flows into the river, or into the drains and then on into the river.

Petrol, diesel and heating oil are supplied to the depots in Barnstaple, including Devon Fuels near the centre of the town and Certas Fuel in Yelland to the west. Road tankers transport petrol to clients across North Devon, such as to the BP station on New Street, at the centre of Torrington. Drivers pull in to fill their tanks and, like the carriers of a virus, they spread the material into every corner of the valleys that feed the Torridge and the Taw.

The petrol and diesel echo the plastics that float down the streams. Shopping bags wrapped around branches by the banks. The plastic fragments of sanitary towels that pass through the sewage works’ shredders and join the rivers’ flow. And then the microplastics too small for our eyes to perceive that coat the bodies of the fish and every living creature.

It is a good audience for the screening of The Oil Machine, the cinema is almost full. And the discussion that follows is vital, rolling out for an hour or so. There is a strong response to the words of Sir David King, the former UK Government Chief Scientific Advisor, who predicts a radical impact from climate change and declares:

“We have to de-fossilise the global economy as quickly as we can.”

How is this to be done, not just at the level of national government policy, but at the local and regional level? How is it to be done in the valleys of the Taw and Torridge?

Perhaps we have to begin by imagining that oil is no longer used as the fuel for vehicles in these river catchments? That the Go Ahead bus is an electric bus, that every car and every lorry is an EV, and every tractor ceases to be powered by diesel. Is this possible to achieve? And if it is possible, how are the steps towards this to be taken? It is not hard to imagine the huge resistance from car owners, farmers, and delivery companies.

But in achieving this shift then we would also achieve the removal of a major source of pollution in the rivers. Not the only pollutant for sure, and not as dramatic as the nutrient and phosphate run-off from farms and raw sewage from sewage plants, but still highly significant.

In The Oil Machine, finance analyst Steve Waygood of Aviva, talks of the intertwined nature of oil and finance saying:

“Angel Gorria, when he was General Secretary of the OECD, talked about ‘carbon entanglement’. What he meant was when you had ministers from the environmental departments coming to the UN meetings and pledging to stop certain activity, lets say drilling. And then they would return home to find the Chancellor of their Exchequer wasn’t prepared to stop that, because of the amount of revenue that the Exchequer received through the tax that was charged on the fossil fuel when it was sold. That that level of entanglement of economic activity meant that we couldn’t simply stop the thing that needed to stop, for in stopping that all other things would also stop too.”

The story is told as a warning, a threat that ceasing to use oil & gas would cause immense disruption.

However in this disruption we may also be able to perceive our liberation. If petrol and diesel run-off is stopped in the valleys of the Taw and the Torridge maybe all other (or the majority of other) forms of pollution will stop too? But to achieve this, to remove the use of all oil in this part of North Devon will require an immense struggle. A struggle to which XR is deeply committed.

*

Many thanks to Cathy Slaughter, Rosie Haworth-Booth, Terry Macalister and Annie Brooker.