Quite suddenly the light has gone. We are left to complete our voyage in the growing dark. The sea charts cease to become legible, the OS map strains the eyes. The words of that fount of all Thames Estuary sailing advice, Charlie Stock, are ringing in our ears

‘When night sailing, do not use a torch.’

There’s a steady south-westerly wind, strong enough to make against the ebbing tide and, despite it being the end of Summer, it is still warm. The prow of the boat ploughs the waves pushing us closer to our destination of mooring and sleep.

We stare at the dark forms of the land. The lights from the distant houses of West Mersea grow in strength, some piercing sharp white, others soft smudging sodium yellow. The profile of the island of Mersea becomes more pronounced against the paler sky, but it is a dark night of cloud through which no stars or moon penetrate.

We have to use our eyes, not to see the land, but to feel it. To caress its shape with our gaze. Finger tips moving across its body in the twilight. We strive to determine the channels that weave into the land. Is this Bessom Fleet? Is that Cobmarsh Island? Is Mersea Fleet really over there?

We drink in the world through the eyes. Staring so hard into the gloom, as though looking into the face of a new born child. Trying to determine the character of the land.

There is the white navigation light of where The Nass beacon should be. Flashing four times and then a pause. We count the beats. They match and we have a clear location. That then must be the entrance to the Mersea Fleet, with the buoys marking the channel into the land. Lower buoy lights flashing weaker green or red. These yachts must be on the line of mooring buoys. Ahead is the silhouette of the shed for packing oysters on Packing House Island. We have reached the sheltered water to which we were sailing. We make fast and raise the tent for the night. Curlews and Oystercatchers call in the dark.

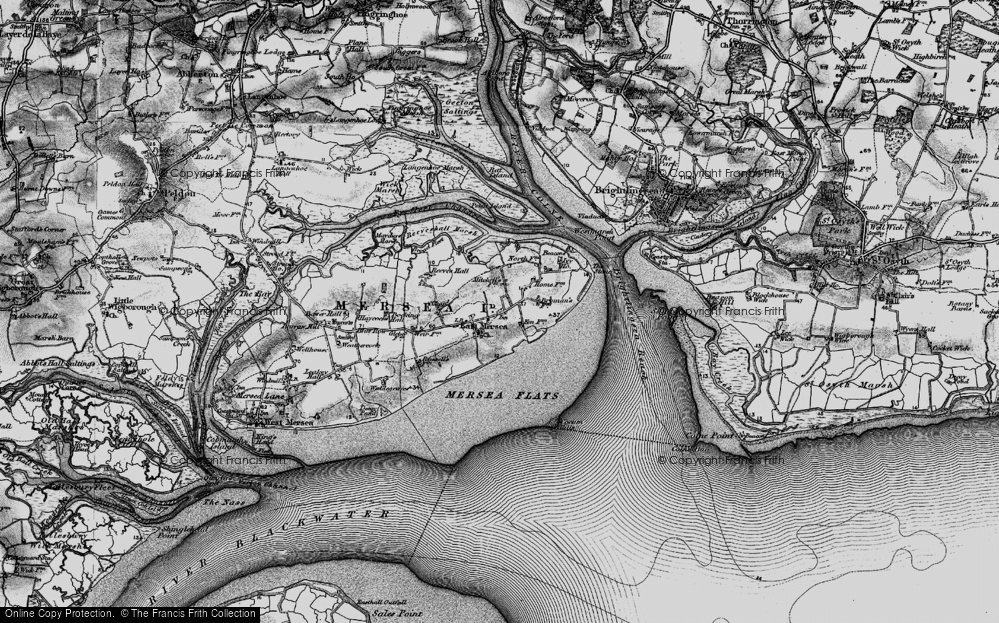

This is an island – Mersea Island – that we have sailed by on several occasions, but never tried to explore. In these past six hours we have completed almost a circumnavigation. Round the north-eastern end, along the shallow Pyefleet channel on its western side up to the Strood causeway that rushes with cars coming on and off the island. Back down the Pyefleet, along the eastern coast of the island facing out into the North Sea, and now around the south-western tip, up the Blackwater estuary, coming to rest in the Mersea Fleet.

I think of all the peoples who’ve lived on the seven square miles of this muddy isle. The hunter gatherers and first farmers whose names and languages are lost to us. (What words did they use to describe Mersea Fleet?) Then those that spoke Celtic and Latin, ploughing the fields, fishing the waters. For this was an epicentre of Roman colony of Britannia, close to the city of Colchester and the towns of Chelmsford and Kelvedon, and protected by the massive fort of Othona. (What names did these people give to the villages on the island?) Then the Angles. Their settling irradicated all the words that proceeded them and they left us the names for Mersea – Mer-sig – ‘The Island in the Sea’

To settle the land. To become settled. To become un-settled. To become restless.

We are caught between these forces, attracted and repelled. But the petrol exploding in the pistons of the engines in the cars on The Strood road fuels that restlessness. We rush everywhere because we do not feel at home. We do not feel at home so we rush everywhere. We are un-settled.

Earlier in the summer I had gazed down on Mersea Island. I was squeezed close between my mother and father in the tight seats of a Lufthansa Airbus A60 hurtling through the sky from Frankfurt to Heathrow. I was helping my infirm parents go on holiday and having the unfamiliar experience of flying. That strange miracle of looking at the surface of the Earth. As in a dream I could see Mersea Island, noiseless at the mouths of the River Blackwater and River Colne. I tried to point out the features of the Estuary to my mother, the towns of Colchester and Maldon. But the land shuttled by like so much television.

We settle down. We settle upon. We settle up. We are settlers in the land.

With each new settlement comes a destruction of language. An epistimicide. Franz Fanon describes with searing articulacy the fight against the settlers in the lands of Algeria. The intensity of violence at the heart of the struggle for survival. I wonder what kind of struggle took place here between the hunter gatherers and the first farmers? Between the first famers and the Celts? Between the Celts and the Romans? Between the Romano-British and the Angles?

Is there a similar struggle now – to understand a new way to settle the land and sea? A new way to describe it. A new web of words and stories. A veil of understanding stretching over the land as we battle against the explosions in the car engines and the roar of the jet engines overhead?

We are trying to find a new settlement out the other side of the petroleum world. We stare at the land about us. We look at it anew.

I’m reminded of the banner that Platform once stretched across an old abandoned goodsyard at the mouth of the River Wandle in London:

The Measure of the New Days is a love of the Surface of the Earth like the Skin of a Lover.

(Thanks to Jane Trowell, skipper)