Yesterday the 19th annual church service called by Stephen Lawrence’s family to honour and remember his life and legacy took place at Hinde Street Methodist Church, London W1. It was a moment to reflect, grieve, and mark all that has happened – the unspeakable and the extraordinary – since his murder in 1993. The occasion made me think more about the ways people balm the wear and tear of activism*.

Platform has been working with the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust on our youth project “Shake! Young Voices in Arts, Media, Race & Power” since 2010. We’ve been bringing together artists and campaigners with young people to explore connections between what happened to Stephen with global issues of social and environmental justice in ex-British colonised contexts, such as the situation in the Niger Delta and elsewhere.

Stephen was murdered on 22nd April 1993, aged 18, in a racially motivated attack by a gang of white youths at a bus stop in Eltham. In January 2012, a conviction of two of the accused was finally secured after 18 years of determined struggle by the family. Their first fight was against institutional racism within the Metropolitan Police at the time, which had resulted in critical neglect of due processes to gather evidence and testimony that would have enabled an immediate carriage of justice. Two of the accused have now received life sentences with minimum terms of between 14 and 15 years, in what Stephen’s mother Doreen Lawrence has called ‘partial justice’.

Yesterday’s service was many things – a testament to the family’s faith, a testament to the support the family have received from their church, an appreciation of family, friends, colleagues and many others who have continued to provide hope and strength through these tough, back- and heart-breaking years. The minister spoke about how remembrance is a collective activity that brings the remembered one vividly into our presence. Atheist or believer, yesterday’s dignified service was very special, a time for contemplation and quiet soul-searching which I valued deeply.

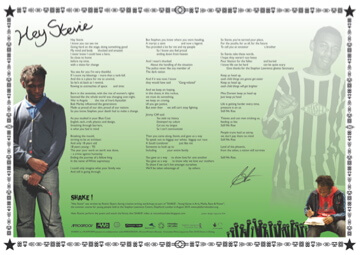

We heard from the Lawrence family’s lawyer Imran Khan who delivered his tribute in the form of a letter he had written to Stephen, the young man he never met but has defended for nearly two decades. This moving direct address reminded me of the poem “Hey Stevie” which was written by young Shake! poet Rotimi Skyers. When Rotimi performed “Hey Stevie”, Doreen was so touched that we designed a limited edition poster of it which he presented to her.

We also heard from Stephen’s brother Stuart, who stepped up to speak alone, but was soon joined by his two-year old toddling son. Stuart eloquently told us how after Stephen’s murder he had vowed not to have children. The devastating impact of Stephen’s death on his mum and dad had been overwhelming for him. But then he spoke of how glad he was that he had broken that vow, and that through becoming a father he understood so much more about what his parents had been through.

He also spoke openly about a particular burden he shoulders: that at some point he will need to tell his son what happened to uncle Stephen. How and when do you do that, knowing what a burden it will be for your son, too?

Keith Ajegbo spoke about the work of the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust and the Stephen Lawrence Centre. Once more it struck me as inconceivable that Doreen Lawrence managed not only to fight so ground-breakingly for justice all these years, but also she achieved something as enormous as set up a pioneering project to help young people like Stephen overcome racism and classism to realise their dreams of becoming creative, influential architects, designers and actors in the world.

The singing from nearby St Marylebone Church of England School’s choir was absolutely gorgeous, and the congregation ensured the family’s chosen hymns rang out.

All in all, regardless of religious belief, this occasion affirmed for me the value of collective moments of quiet reflection and remembrance for people involved in struggles for social and environmental justice. These occasions build community, but more importantly, they make space for complex, slow, vulnerable feelings to be acknowledged. These feelings may start from the purpose of the occasion but seep through our consciousnesses like a kind of massage for the soul – I experienced anger, grief, disbelief, shame, loss, admiration, hope, determination… an ache for humanity’s ugliness and also our incredible beauty. Knowing that others in the room were also grappling with some of these feelings helped my reserves to be nourished at a very deep level. Such nourishment can sustain us, help us to keep going, and see us through tougher times. Of course, all religions know this, but in my experience atheistic activists and campaigners (like me) can often forget to make equivalent occasions for this sustenance to take place.

Stephen’s service reminded me of the morning of 10thNovember 2005, in a windy spot on the South Bank in London, where Platform, the Remember Saro-Wiwa coalition and about 200 people

marked the 10th anniversary of the execution of Nigerian writer and environmental campaigner Ken Saro-Wiwa. We also solemnly commemorated each of those Ogoni men who had been executed on the same trumped-up charges as Ken. A number of people shared powerful words, including Ken Wiwa jr, Anita Roddick, and Wole Soyinka.

Maria Saro-Wiwa, Ken’s widow, had told us she wouldn’t feel able to speak. But suddenly, after campaigners from the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People had spoken, she walked up onto the stage. She introduced herself, and said she would sing the Ogoni national anthem.

Joined by strong voices from MOSOP, the anthem rang out towards the Shell Centre while her son and grandchildren – and all of us – listened, electrified.

It was one of those shared moments that becomes indelible, like a line in the sand, a collective strengthening of resolve, a map to the future.

After a pause, we announced the winning ideas for the Living Memorial to Ken Saro-Wiwa and set to work.

* see previous blog