Recently I gave a short talk followed by a lengthy discussion in a ‘Green Drinks’ forum organised by Artsadmin at Toynbee Studios in Whitechapel, London. The audience was comprised mainly of people in the arts engaged with ecology, and people in the ecological movement engaged with the arts. The text of the talk ran as follows:

Everybody that comes to a ‘Green Drinks’ event such as this surely shares a similar view on at least one thing – the seriousness of climate change. We’ll no doubt agree that a radical change is taking place in the composition of the atmosphere, that this change is already having major social impacts, and that the rate and scale of change is likely to increase. In relation to the Earth’s ecology, none of us here will hold a position of what I’ll call ‘ironic detachment’. All of us will think that ‘something must be done’, and all of us try to play a part in that ‘something’. Occasionally we’ll fall foul of a melancholy passivity, but most of the time, if we’re able, we’ll try to shut those feelings out . What is intriguing is how different sentiments can sometimes arise among us when we consider not climate change, but art, politics and activism.

Recently a dear friend took me to see the new Jeremy Deller exhibition, English Magic, at the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow. Deller’s work, which was taken from his show at the Venice Biennale 2013, is hung in two rooms amongst the permanent exhibition on the life of William Morris. I like Deller’s work – I think he’s bold, funny and I enjoy the fact that, after such a drought of contemporary art that directly addresses political issues, we can see in mainstream galleries political art like Battle of Orgreave. Much of his work engages directly with a general public as with It is what it is – or effects actual changes in the world beyond the art world – such as The Bat House Project.

However English Magic felt different. The pieces give representation to the Invasion of Iraq, the death of Dr David Kelly and the outrageous levels of inequality that are embodied in Roman Abramovic’s monstrous private yacht. It’s easy to perceive the anger that Deller feels at the injustice he sees. But somehow, for me at least, there is a fatalism about the work. A sense that ‘All this in the world is wrong, but nothing can really be done.’ A melancholy passivity pervades. Furthermore, despite Deller’s interestingly engaged and collective practice, the pieces seem to lie under that pall that overshadows so much contemporary art, the pall of ‘ironic detachment’. A sense that to try to ‘do something’ would be naïve, would be unseemly and inevitably doomed to be unaesthetic or ‘ugly’ and ‘preachy’. A sense that we have no agency, that despite our anger at what we see in the world we cant ‘do something about it.’

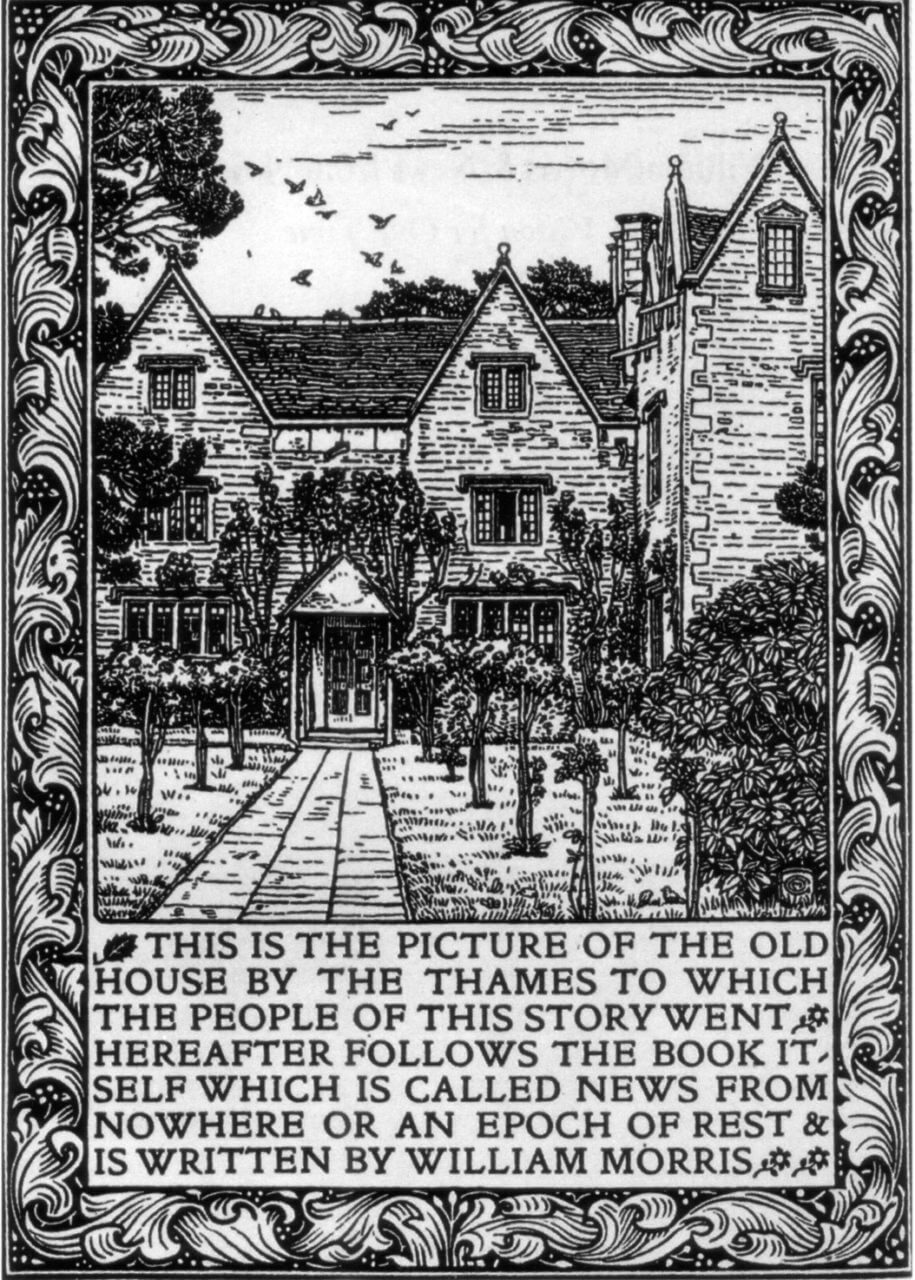

By contrast, there’s one room of the gallery’s permanent William Morris exhibition that I found particularly striking. Entitled ‘Fighting for a Cause’ it covers Morris’ work as an activist. There are pamphlets of revolutionary songs that he wrote, the frontispiece of his utopian novel ‘News from Nowhere’, and a banner from the political organisation he helped found – the Socialist League. Most intimate and breathtaking, is his satchel hung in front of a list of all the talks that he gave in one year – over 100, everywhere from street corners to public institutions. Morris had originally come to his art as part of the Pre-Raphaelites, and his closest friend Ned Burne-Jones was that group’s iconic painter. Burne-Jones’ vast canvasses portrayed the beauty of the world as lying in the past. To me, they convey the sense that that beauty had been destroyed, or was being destroyed and there was nothing to be done. They are distillations of a melancholy passivity.

It is remarkable, given the context of his peers, that Morris found a fire that drove him to have hope in the future and a determination to fight tirelessly for it. His novel ‘News From Nowhere’ is set in the early 21st century. The narrator falls asleep in 1890, and wakes to find himself in about 2014. The Revolution has taken place in about 1950, and a generation or so later the Thames Valley, through which the narrator travels, is utterly transformed. There is no money or property, there is no government or industry, there is no distinction between art and life, and what we would call the eco-systems devastated by Industrialism have come back to life. The Thames is plentiful in salmon, which were more or less absent from the river a decade before Morris was born. This was the future for which Morris yearned and fought.

Morris was a major cultural figure in Victorian Britain. He was one of the leading designers of the day and had been slated to replace Tennyson as poet laureate when he crossed what he called ‘the river of fire’ and became a revolutionary socialist. Many of his artistic contemporaries thought that his new work was naïve, unseemly and inevitably unaesthetic. His ‘crime’ was to step out of representation and into action, to move from fatalism into a determination to agitate for the building of a different future. He talked of his work as the ‘Education of Desire’, as he tried to ensure that the world ahead would be different from the injustice he saw around him. Near the opening of News from Nowhere the narrator says of the social order of which he dreams: “If I could but see it! If I could but see it!” Morris was scorned by many because of his work to bring that dream into being. Because he moved from representing the injustices of the world, to actually trying to change the world. Because he became not mere a ‘political artist’ but an ‘activist artist’.

William Morris Gallery – documentary – Fighting For a Cause from Hazel Lee Kelly on Vimeo.

Of course Morris is not alone in this. There have been, and are, thousands of artists for whom the focal point of their work, their key medium, is social change. That change is the substance with which they have worked, like a potter uses clay or a photographer the lens. Sylvia Pankhurst, Joseph Beuys, Vladimir Tatlin, Dominique Mazeaud, Guillermo Gomez Pena, The Guerilla Girls, the Art of Change, the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination … the list is long. Each of them have asserted new definitions and roles for art within society, and each has been driven by the urgent need for change. This political urgency and new forms of aesthetics have often earned them severe criticism from the mainstream as an affront to ‘art for art’s sake’, or art with an ‘ironic detachment’.

Over the last three years Platform has played a central role in a gathering of arts organisations. This grouping, which has no official name, is open to new participants and is slowly growing. Alongside a number of individuals, the group includes the organisations, Julie’s Bicycle, Tipping Point, Live Art Development Agency, Cape Farewell, Artsadmin, Arcola Theatre, Centre for Contemporary Art & the Natural World, Visual Arts & Galleries Association and CIWEM.

The group started with London-based organisations that had something in common in terms of ecological aims. We were all addressing questions of ecology and especially climate change through our art, and we had all achieved a profile for this work within the sector. We had all been in receipt of Arts Council England (ACE) project funding, whilst some had received core finance from ACE. And we had all just applied for to the new core scheme known as the National Portfolio Funding. A more ominous link was made between us in March 2011, when it became clear that almost all those organisations whose core aim was to tackle climate change had been turned down.

On the suspicion that the climate change factor was the reason we were rejected, we got together. Driven by a shared sense of anger, and supported by other arts organisations, we expressed our concerns to the head of Arts Council London and demanded that we have a meeting with senior staff. After a couple of months, 13 of us were sat round a table with 7 senior Arts Council officers.

And things have really shifted from that moment of action. They might have come about by their own accord – there are people in ACE who are passionate about tackling ecological issues – but it’s difficult not to conclude that our collective activism spurred things on. In the years that have followed that first meeting, ACE has made it a requirement of NPO-funded organisations that they undertake an environmental audit and show how progress will be made. This was announced by Alan Davey at TippingPoint‘s ACE-funded national event in Newcastle in 2012. ACE have contracted Julie’s Bicycle to foster these ecological practices into the day-to-day operations of grant recipients, helping them to reduce their carbon footprints. ACE has redrafted its Strategic Framework, and delineated one of its Five Goals as: ‘The arts, museums and libraries are resilient and environmentally sustainable’. Thereby committing the organisation to try to ensure: ‘The cultural sector embraces environmental sustainability and has reduced its carbon footprint’. In July 2013 the board appointed Jane Tarr to be the Arts Council’s first Director of Organisational Resilience and Environmental Sustainability.

Looking back on the past three years, I see that we have kept together as a group and slowly grown, expanding to welcome organisations and individuals from outside London. But it feels as though we’ve been doing something more than demanding the Arts Council fund ecologically-driven arts organisations, or lobbying for policy changes at the heart of ACE.. We have become a group that wants something in the future and are prepared to work together for it. People who refuse to be fatalistic about the collapse of public financing of art that directly engages in questions such as climate change. People who are not resting in melancholic passivity about the hollowing out of the Arts Council, and who are not just trying to defend an important part of what could be called the Post War Social-Democratic Settlement, but trying to, tentatively, build something new. We are, in a small way, what Morris described, a Community of Desire.

One of the things that’s intriguing about the activity of the past three years, is that it is easy (certainly for Platform) to see the group’s process of meetings, minutes and occasionally a public statement, as somehow outside the mainstream of our artistic practice. It is easy to relegate this work to the realm of ‘an expanded concept of fundraising’ – a means of getting the money to do the ‘real work’. (Although Julie’s Bicycle’s actions stand out slightly distinct from this.)

But what if we were to look at this work as a kind of activist art project that we are collectively engaged in? We are, after all, all artists in one form or another, and we are engaged in trying to make the world differently. I think we are engaged in a form of activism.

If we spend time considering how climate change will impact on the world, we soon come to ask ourselves questions with wide-ranging implications, such as: What kind of society will arise in London or England in response to the pressures – amongst other things – of rising sea levels, of droughts and floods, of food and water scarcity and a constant stream of humanitarian crises across the world? What kind of society do we want to help build in the face of these challenges over the coming ten, twenty, thirty years? And in such a society, what kind of support, through public financing or other means, will there be for art that addresses climate change? If we address these questions we might begin to approach the kind of breadth of imagination that Morris exhibited.

Once again, most of us in this room surely understand that addressing the challenge of climate change will require the rapid cessation of the use of all fossil fuels. We know that although vital, radically reducing the carbon footprint of our arts organisations is only part of the ‘solution’. Another part of the ‘solution’ will be to radically reduce the power of those companies whose profit comes from the extraction of fossil fuels, the international oil & gas and coal mining corporations. A significant step in cutting back that power will be the cessation of cultural institutions taking sponsorship from the likes of BP and Shell, and thereby bolstering the social acceptability of their core activity.

The ending of the financial relationship between BP and the Tate will not in itself be the ‘solution’ to climate change, of course. But at the same time, in the kind of society that we need to become in order to address climate change, there will be no place for corporations that profit from the extraction of fossil fuels, and no place for the use of even a fraction of those profits in the financing of cultural institutions. In the Australian arts scene since the furore over the boycott of the Sydney Biennale by artists protesting against sponsorship by a company operating mandatory detention centres, there is a massive debate around ethics, finance and art. A similar national debate is growing in this country. We need a great many artists, cultural commentators, curators to ‘cross the river of fire’, to move from passivity to action and publicly speak out on these issues.

This work, to help create a new code of ethics for the funding of cultural institutions, is a form of activism in the realm of the arts. It could be seen as a sister to the work of the grouping described above, which is trying to help create a national arts board that sees addressing climate change as a core part of its remit. Just as it came to see addressing discrimination on grounds of race and disability as a core part of its remit after the sustained pressure of many artists and activists in the 1970’s and 80’s. Both lines of pursuit are forms of activism. What happens if we approach them as forms of art? Are we able to use our imaginations, collectively, to consider these issues in the broadest way? What if we use our aesthetic sensibilities to give form to that process of consideration? To create some artwork, or artworks, that inspire the desires of others? What forms would this work take? What happens if we make this activity we’ve been engaged in part of our practice, part of the ‘real work’? If we overcome any feeling that it might be somehow naïve, or unseemly, or unaesthetic to be engaged in changing the nature of an English state institutions? Engaged in both dreaming of a different future and working to realise that future.

Many thanks to Peter Gingold of TippingPoint, and Judith Knight & Mark Godber of Artsadmin.