Azerbaijan’s President, Ilham Aliyev, gave a speech last week accusing oil company BP of “false promises” and “gross mistakes”. In a country where regime and corporation are closely intertwined – and almost symbiotic – what is going on behind the political theatre? Why the public outburst?

Azerbaijan’s President, Ilham Aliyev, gave a speech last week accusing oil company BP of “false promises” and “gross mistakes”. In a country where regime and corporation are closely intertwined – and almost symbiotic – what is going on behind the political theatre? Why the public outburst?

Aliyev revealed that Azerbaijan had lost $8 billion in revenues due to an “unexpected decline” in oil extraction by BP, the largest investor in Azerbaijan and operator of both the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli (ACG) and Shah Deniz mega-fields, vowing to take “serious measures”.

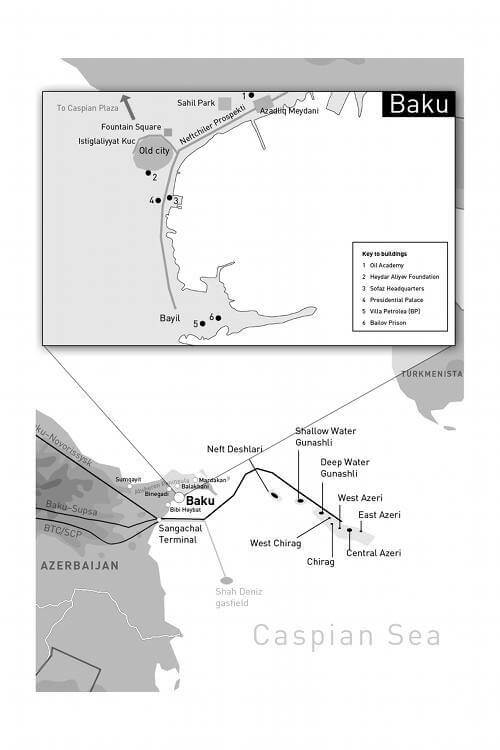

For years, BP widely promised that it would extract 1 million barrels of crude every day from deep beneath the Caspian, and pump it through the trans-Caucasus Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline. The company was so assertive that when we were travelling along the pipeline route in 2009, BP officials told us they were upgrading the infrastructure to carry 1.2 million barrels a day.

Yet this October, only 574,196 barrels a day were scheduled to be pumped through BTC – less than half its capacity. Why the dramatic drop-off?

According to Aliyev, BP stopped prioritising an increase in oil extraction after the contractual division of oil shifted. The ACG Production Sharing Agreement, known as the “Contract of the Century”, sets out that once BP had made a certain level of profit, the split in profit oil would shift in favour of the Azeri state. After years of delays from BP, this finally took place in 2008.

In his speech, Aliyev revealed the extent of BP’s massive profits in Azerbaijan. After investing $29 billion in offshore drilling platforms, processing plants and pipelines, the company walked away with a whopping $73 billion in profits. In comparison, Azerbaijan’s State Oil Fund – intended to ensure long-term macro-economic stability and to diversify the economy – is looking pretty meagre at only $16 billion.

An unexpected slump or a predicted peak?

Aliyev’s regime is built on carrots and sticks. The hard stick of repression and censorship, and the carrot of a promise that Baku will become the Dubai of the Caucasus. The construction boom in recent years gave people optimism for the future – after all, Dubai has many skyscrapers.

But the current drop in oil extraction will mean lower oil revenues paid to the Azeri state. This means less flexibility for the rentier state, and greater limits on both social and military spending. By coming out strong against BP, Aliyev is hoping to direct responsibility away from his government and onto the corporation.

While BP has undoubtedly made excessive profits at the expense of the Azeri people, is the decline in oil being pumped really as “unexpected” as Aliyev claims? Our visit to BP’s Sangachal Terminal near Baku in 2009, described in Chapter 5 (The Wide Stream of Oil gushed over the Greasy Earth) of The Oil Road, suggests otherwise:

Among [BP presenter] Orxan’s slides there is one particularly striking image: a graph of the history of oil production in Azerbaijan. It shows four peaks: in 1904, 1941, 1968 and 2010. […] The slide also shows that after the peak of 2010 comes a predicted rapid decline. This graph, in fact, illustrates exactly what we have heard many times in Baku from concerned critics: that despite government and corporate claims, Azerbaijan is reaching ‘peak production’. Emil Omarov of the National Budget Group had told us, ‘But now, when people hear that the oil production will peak next year, they ask where the benefits have gone. On the streets, you can see fancy cars. Cars made in German factories in Bavaria will be seen here before they are seen in Munich. But it is only a small part of our society that is living in luxury, while many remain in poverty.’

The prospect of rapidly declining revenues is not new in Azerbaijan. There were ‘Oil Slumps’ in the 1910s, the 1940s and then in the 1970s. Each time, these have been accompanied by moves to diversify the economy away from the simple extraction and export of crude. The oil baron Taghiev sold out his holdings to the British financier James Viashnau at the turn of the century, and invested in cotton mills, a caviar farm, and agricultural projects. [Petrochemical centre] Sumqayit represents [Stalin’s colleague] Orjonikizde’s 1930s drive to create petrochemicals and industrial products from the raw materials that flowed from the Absheron Peninsula. Soviet Azerbaijan in the 1970s and 1980s under [Ilham’s father Heydar] Aliyev increased investment in the production of vegetables and cotton.

The question arising from Orxan’s data is: How will Azerbaijan navigate the coming ‘Oil Slump’? This is precisely the challenge that the State Oil Fund is supposed to address, but the ‘six new bridges, lots of roads and tower blocks’ that Orxan celebrates cannot solve this problem.

Aliyev is right that BP has ripped off Azerbaijan. And yet, we should beware being taken in by the political theatre of a clash between regime and corporation, distracting from the economic and political reality the two chose to create together. BP’s oil extraction in Azerbaijan was always going to ramp up sharply to a peak, and then drop off almost as quickly – that’s how the company planned it, to maximise short-term profits.

As veteran oppositionist Zardusht put it: ‘The oil will end, BP will leave, the elite will move to their fancy houses in London and Paris. And what will be left behind?” Lots of empty skyscrapers that we can’t keep clean.’