I’m holding in my hands a report published by Amnesty International in November last year – ‘A Criminal Enterprise? Shell’s involvement in human rights violations in Nigeria in the 1990s’. It analyses in forensic detail exactly how much Shell staff knew about, and were involved in supporting, the actions by the Nigerian military taken against Nigerian citizens living in Ogoniland. Actions that resulted in the the deaths of hundreds of women, men and children, the destruction of whole communities and ultimately to the judicial murder of nine Ogoni leaders including Ken Saro-Wiwa on 10th November 1995.

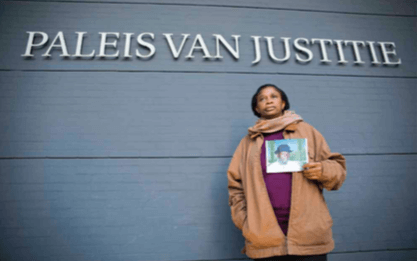

An extremely well researched and written document, created by Mark Dummett and a team of others, it is a powerful indictment of Shell’s operations and is likely to prove vital in an ongoing court case in Den Haag. For Esther Kiobel, widow of Dr Barinem Kiobel, has taken Shell to court for its complicity in the killing of her husband. After nearly 25 years of grieving and struggling it is just possible that Esther Kiobel will find some justice in a Dutch court. For the Kiobel case was not part of the out-of-court settlement reached between Shell and the families of Ken Saro-Wiwa, and others, in June 2009.

But the report in my hands stands for more than this, for it is a testament to the power of communal memory.

I think of the line by the Czech author, Milan Kundera, in his novel ‘The Book of Laughter and Forgetting’:

“The struggle of man (sic) against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting”

Platform used these words as a mantra to guide our Remember Saro-Wiwa and then Action Saro-Wiwa projects running from 2004 to 2015. However I am now struck by the wisdom of these words anew.

On page 14 of ‘A Criminal Enterprise’ it reads:

‘Methodology – This report draws on a wide range of archive material, dating back to the 1990s. These include court records, company documents, letters, Nigerian and international newspaper articles from the 1990s, reports by Amnesty International and other organisations, official Nigerian government reports, documentary films, academic articles, memoirs and other historical accounts.’

There are four footnotes attached to this paragraph.

I look at the bottom of the page and 29 lines of small print that list all the publications which have been drawn upon. The litany of authors, recorded alongside some of the books and papers, includes – Michael Birnbaum QC, Steve Kreztmann, Glen Ellis (of Catma Films), Ide Corley, Helen Fallon, Laurence Cox, Stephen Ellis, Andy Rowell, Lorne Stockman and myself, Jedrzej George Frynas, J. Timothy Hunt, Karl Maier, Ike Okonto, Oronto Douglas, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and his son Ken Wiwa.

This row of names is a mere fragment of the community of people who gathered around the Ogoni struggle in the 1990s, or have been drawn to it in the past twenty-five years. This community is spread around the world. Many people within it we have known, or worked with, at Platform. With only a short reflection we could add fifty, may be a hundred, names to this list. The first that spring to mind are Lazarus Tamana, Celestine Akpobori, Eno Usua, Nick Ashton-Jones, Irene Gerlach, Maria Saro-Wiwa, Nnimmo Bassey, Asume Osuoka, Jo Hurst-Croft, Eveline Lubbers, Jane Trowell, Ben Amunwa, Sokari Douglas-Camp, David A Bailey, Dan Gretton, Tim Sowula, Sue Dhaliwal, Sarah Shoraka, Gordon Roddick, Anita Roddick, Bevis Gillett, Diana Morant, Andrew Conio, Judy Price, John Vidal, Ed Pilkington … The list goes on.

It seems that the point about reciting these names is that it reminds me just how big this community is, and that within it, within its collective understanding, lies something extremely resilient. As a community it’s energy is sustained by the inspiration of the remarkable Ogoni people who have had to live with the impacts of oil drilling on their land for three generations and yet have never ceased resistance despite the most brutal repression that this report illustrates.

As Kundera’s line makes out, the wish of the powerful – and in this case the past and present executives at Shell – is that we should forget, that we should ‘move on’, from the crimes committed in the 1990s and since. It is the web of connections between people, of friendships in the international community and with the communities in Nigeria, which provides the greatest obstacle to the ‘forgetting’ that is desired by the wealthiest corporation in Europe.

This community is not merely a gathering of mourners, or nostalgics, or campaign veterans, it has the capacity to be a powerful force that can provoke political change now and in the future. Its strength lies in supporting each other to continue to demand justice and reparations, and in the maintenance and use of its communal memory.

I am struck by a practical example of this communal memory. Attached to the line in the above passage that reads ‘court records, company documents, letters, Nigerian and international newspaper articles from the 1990s’ is a footnote:

‘1. With thanks to Andy Rowell.’

Andy has been one of the most vigilant of the keepers of the memory around Shell in the Niger Delta. He was a friend and ally of Ken Saro-Wiwa before he was murdered, and has studied and published upon the issue for nearly three decades.

But not every piece of information is stored within the skull. We humans need to keep data outside our craniums. The keeping of records, both hard copy and digital, is vital if we are to articulate memory. This is as true of photographs of our lovers, as it is of an internal memo from Shell Nigeria.

Andy had gathered together five boxes of papers mostly covering Shell’s activities in the Delta in the 1990s. A while back he and his family were moving house and he needed to reduce the amount of stuff that he had. We gave the boxes shelter in the Platform Archive. Part of that Archive is housed at the wonderful Bishopsgate Institute at the heart of The City of London, and part of it lies in a discreet location beyond the fringes of the metropolis.

Andy’s boxes lay in the Archive, quietly, until one day they were brought out into the light, were picked over, and came to inform a key part of ‘A Criminal Enterprise? Shell’s involvement in human rights violations in Nigeria in the 1990s’.

It is a fine thing that Shell should be held accountable after so long, and part of the mechanism that enables this to happen is a web of friendships, a communal memory and the practical infrastructure of an Archive.

Together we shall not forget and continue to hold Shell to account.

With thanks to Andy Rowell, Sarah Shoraka and Lazarus Tamana