This is a Guest Blog by Will Essilfie, educator and researcher, on Platform’s event ‘The Tent that Can Hear‘. In this event, Platform looked back at ecological issues in London in 1989 when we made the ‘Tree of Life, City of Life’ project, and forward to 2049. This was a 30th anniversary return as the Platform tent had been sited at nearby Greenland Dock for Tree of Life.

The Tent that can Hear took place on 4th May 2019 at Stave Hill Ecological Park, near Greenland Dock, London, as part of the annual celebration for International Dawn Chorus Day, Soundcamp 2019.

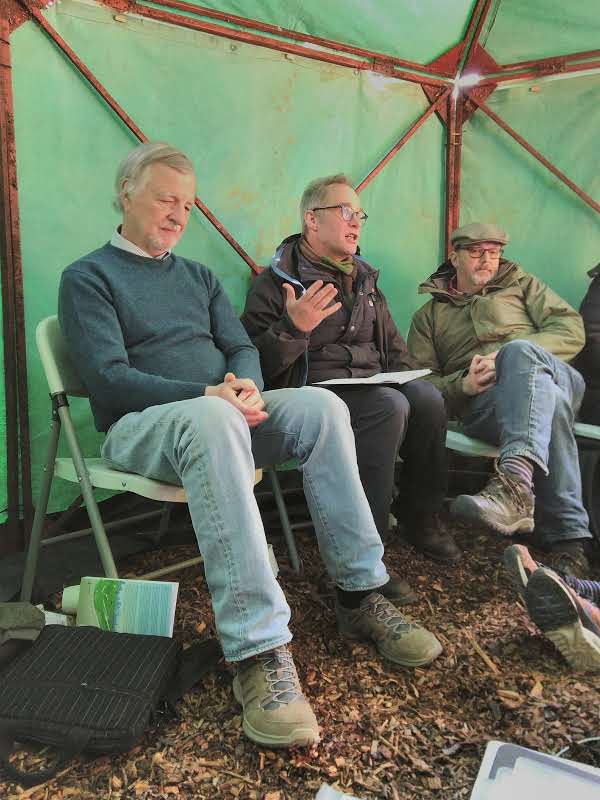

Applause resounded through the seven-sided pea green tent after Herbert Girardet read his poem ‘Compelled to Be Wise’. This was the ending of an engaging two-hour discussion ‘The Tent that Can Hear’, facilitated by Jane Trowell as Platform’s contribution to Soundcamp 2019. The speakers were Platform’s James Marriott, former Platform member John Jordan via video link from La ZAD in Brittany, and cultural ecologist Herbert. They were responding to questions that Hajra Gulamrassul and I conceived.

For two hours the audience assembled in the tent experienced a range of weather from rain to sunshine to cloudy skies, at a slightly cold temperature which remarkably did little to lessen the vibrancy of the discussions. Due to the number of people who turned up for the discussion, which exceeded the admittedly limited capacity of the tent, a few panels were removed to makes it easier for everyone to see and hear. This probably added to the chill, making me contemplate what it must have been like for James and John to live in the tent 30 years ago for a total of two and a half months.

Spooling back for a bit, my own journey to the tent at Soundcamp began weeks before, when Hajra and I were invited by Platform to visit their archive housed at the Bishopsgate Institute, to research the 1989 project, Tree of Life, City of Life. Other than a basic overview – James and John living in a tent at 5 sites along the River Thames whilst exploring the metabolism of London – I knew next to nothing about the project.

Over two half days, I immersed myself in the archive, reading documents created at the time of the project.

This included research in the form of notes, newspaper articles, minutes of progress meetings, letters appealing for sponsorship, evaluation reports and photographs. The process of accessing this information involved searching through the extensive catalogue to identify specific reference numbers for the documents for retrieval. Once the archivists delivered the yellow folders containing these documents to me, I read through the contents to build up an understanding of the project, particularly the way it developed. In the comfort of the library, exploring events of three decades ago in a London that was in many ways very different from now, I was reminded again and again that the city is still facing a number of the same problems the Tree of Life project set out to address.

James and John, during their durational performance which consisted of two weeks at each of the five sites, were primarily there to ‘listen’ to the city. Working with a small team that included a cultural ecologist (Herbert), historian Rodney Mace, economists Teresa Hayter and Nick Robins, photographer Jens Storch, filmmaker Pete Durgerian, and administrator Ana Sarginson, James and John were able to build up a unique understanding of London, in both the past and in 1989, of how the city operated. In their research this capital city came across as a voracious organism consuming resources from around the world to build up its wealth [i]. The team’s insights into this consumption by the city as well as the waste produced by the activities of its inhabitants, served to underpin conversations with local people [ii] wherever the tent was sited.

Sitting with James and John in the very same tent they had conducted the original project in, they cast their minds back to reawaken their memories of what it had felt like at the time. Listening to their reflections on how the project had gone on to influence their lives, I was struck by how their words added colour to the documents I had read in the archive. Despite the numerous types of information on the project I had encountered, there had been gaps in my understanding of the day-to-day experiences of the project. James spoke about how camping at Nine Elms in Vauxhall really brought home to him “the destructive impact of cars… a symbol of privatization” as hour after hour the steady flow of vehicles past the site conducted a relentless level of noise and intensity. John informed us that the experience of the project had “radicalised him [and] changed the way he saw the world”. They both also acknowledged that though the project and its associated exhibition may not have adequately communicated to the public the insights and knowledge uncovered at the time, it dramatically changed everyone who was involved in it.

Hearing about the kind of work James and John went on to do following the end of the Tree of Life project, it’s clear that the project significantly impacted their work, the development of Platform, John’s art activism in many contexts, and subsequently the lives of numbers of others. I guess more than ever I now see that the learning from social justice projects can in many ways be just as important for the instigators, if not more so, than the public the project is aimed at engaging with. In the end my exposure to Tree of Life, City of Life has left me with the feeling that looking at the numbers of people who experience an art activism project in an audience/participant capacity or directly witness it as a passerby can do the project a major disservice; some of the greatest impacts can occur where least expected.

You can watch the original Tree of Life film ‘Greenland Dock’ here (16 minutes)

[i] This brings to mind a handful of novels with alternative conceptions of the city of London – The Drowned World by JG Ballard (1962), Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman (1996), Un Lun Dun by China Mieville (2007), Mortal Engines by Philip Reeve (2001), and A Darker Shade of Magic by V.E. Schwab (2015). The London of Mortal Engines physically ‘eats’ towns and cities!

[ii] A non-fiction book about urban planning policy worthy of exploration is The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs (1961).