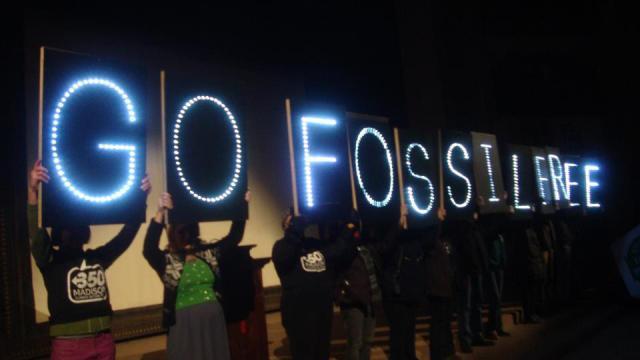

Divestment is very much the climate campaign buzzword at the moment. Tonight in London there’s the culmination of the Fossil Free Europe tour with divestment doyen Bill McKibben hoping to emulate the success of the States-side campaign over here, while last week we co-published with People & Planet and 350.org the report Knowledge and Power – Fossil Free Universities that revealed the extent of the financial relationships between the UK higher education sector and oil and gas companies. A study from the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at Oxford University argued that the campaign to persuade investors to take their money out of the fossil fuel sector is growing faster than any previous divestment campaign and could cause significant damage to coal, oil and gas companies.

Divestment is very much the climate campaign buzzword at the moment. Tonight in London there’s the culmination of the Fossil Free Europe tour with divestment doyen Bill McKibben hoping to emulate the success of the States-side campaign over here, while last week we co-published with People & Planet and 350.org the report Knowledge and Power – Fossil Free Universities that revealed the extent of the financial relationships between the UK higher education sector and oil and gas companies. A study from the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment at Oxford University argued that the campaign to persuade investors to take their money out of the fossil fuel sector is growing faster than any previous divestment campaign and could cause significant damage to coal, oil and gas companies.

Some critics have argued that the divestment campaign is ill-judged in that it won’t cause significant financial harm to the fossil fuel companies because their profits are determined primarily by the demand for their products rather than their stock prices. The president of Brown University recently explained their decision not to divest by arguing that their investiture was too small to make any significant impact.

But to focus on the financial impacts of divestment is to miss the much more significant consequences of the campaign – the stigmatization. As the Oxford University divestment report asserts, “The outcome of the stigmatisation process, which the fossil fuel divestment campaign has now triggered, poses the most far-reaching threat to fossil fuel companies and the vast energy value chain. Any direct impacts pale in comparison,” and Bill McKibben admits that, “the odds of bankrupting Exxon are pretty small, but I think the odds of politically bankrupting them are higher.”

As with individuals, a stigma can produce negative consequences for an organisation. For example, firms heavily criticised in the media suffer from a bad image that scares away suppliers, subcontractors, potential employees, and customers. Governments and politicians prefer to engage with ‘clean’ firms to prevent adverse spill-overs that could taint their reputation or jeopardise their re-election. Shareholders can demand changes in management or the composition of the board of directors of stigmatised companies. Stigmatised firms may be barred from competing for public tenders, acquiring licences or property rights for business expansion, or be weakened in negotiations with suppliers.

Framing this strategy around the goal of undermining the social legitimacy of fossil fuel companies means that the divestment campaigns are the natural bedfellows of the campaigns and interventions that have been taking place in the UK over the issue of oil sponsorship of the arts. Working alongside groups like Liberate Tate, the Reclaim Shakespeare Company, Shell Out Sounds and UK Tar Sands Network, we’ve been working to drive a wedge between the long-standing relationship between BP & Shell on one hand, and most of the UK’s most prestigious cultural institutions. Not because we think that in and of itself this will stop BP & Shell from (for instance) trashing Canada for tar sands, but because we see these relationships as being one of the means that enables oil companies to maintain a public perception of being respectable corporate entities.

Big art institutions like the Tate or the Southbank Centre have certain parallels with universities. They’re mainly public institutions and run on public money, but more importantly these are institutions that we look up to in society. Arts and education both embody some sort of noble ideal of what is “good” about society. This notion might be contested as being highly romanticised by anyone involved in the murkier day-to-day pragmatism of running either type of institution, but it’s one that still carries a lot of currency. And that’s why the idea of arts and education institutions consciously distancing themselves from fossil fuel companies is particularly resonant in the campaign to stigmatise oil companies.

Arts sponsorship activism represents a sort of cultural divestment – and it should nestle comfortably alongside the growing wave of university (and pension) divestment activities taking place in the UK. Whereas students may see themselves as being key stakeholders in the debate over university endowments, anyone who sees themselves as being an arts aficionado or an occasional gallery goer should see themselves as being a possible agent of change in putting pressure on Tate and others to drop oil sponsorship. Many of these big arts institutions have paid membership schemes which are natural arenas for making your voice heard. Tate members have been very vocal at the last couple of members’ AGMs that take place in December.

It’s great that the zeitgeistiness of the US divestment campaign is inspiring action in Europe, and hopefully it’s work that can and will mutually support the other existing drives to strip fossil fuel companies of their ‘social licence to operate’ through association with highly prized cultural institutions. By creating and informing a public debate that questions the legitimacy of these companies in being associated with universities and art galleries, we can strengthen attempts to hold them accountable in other political and financial spheres. This is an essential step in ending the stranglehold that the companies have on the corridors of power – a major obstacle that we face in the transition to a low carbon society.