The days tip towards the darkness of Winter. The world of the North comes into our lives. The year stops and takes a breath. It pushes me to reflect on the months past. It makes me think of you Doreen and how you would have loved these times. You’d have been everywhere. In your element, plugged into the energy of new beginnings. I have missed your presence but I know that you’ve been here, and honour of that I’ll post these words.

Hannah Arendt, when deep in the study of Rahel Varnhagen, declared that this late eighteenth century German-Jewish writer was her ‘very closest woman friend’, despite being dead for over a century. It is over a year and a half since your death Doreen, and you remain of course a friend very dear to me.

As you know, the eighteen months since you passed have been ones of extraordinary political convulsion with the Brexit Referendum, the US Election, the first months of Trump’s Administration and then the UK General Election. At the conference held in your honour a year ago so many attendees, dazed by the turbulence, said “I wonder what Doreen would have made of this?” or “I wish Doreen was here to ask her opinion”.

But have you really gone? I feel now the need for another conversation with you. Let this one unfold in a myriad of directions as they always have done.

I once saw the Catalan musician Jordi Savall perform a concert in memory of his late wife the singer Monserrat Figueras i García. (You too love Catalonia. How you would have been gripped by recent events there.) At one point, he announced “The dead only die when the living cease to remember them”.

Strangely in our discussions we’ve never talked about death, nor about faith. I suspect that you are profoundly atheist. That for you death is final. That when the body ceases to function, there is no existence. I think of the lines of Sylvia Plath:

‘The heart shuts,

The sea slides back,

The mirrors are sheeted’.[1]

And a most beautiful passage by John Berger:

‘What reconciles me to my own death more than anything else is the image of a place: a place where your bones and mine are buried, thrown, uncovered, together. They are strewn there pell-mell. One of your ribs leans against my skull. A metacarpal of my left hand lies inside your pelvis. (Against my broken ribs your breast like a flower.) The hundred bones of our feet are scattered like gravel. It is strange that this image of our proximity, concerning as it does mere phosphate of calcium, should bestow a sense of peace. Yet it does. With you I can imagine a place where to be phosphate of calcium is enough.’[2]

Perhaps this is how you foresaw it, to be mere phosphate of calcium? Perhaps this is how it is for you? But for me, in these same hours, you are vital and constantly present. Is it not possible that these two realities can co-exist?

*

I’d had the great fortune to meet you through Platform’s work. You somehow came across our Homeland project in the mid 1990s. I think you were drawn to the fact that we too were trying to grapple with the questions of globalization and geography, and to find ways to explore them through the arts. We had the odd exchange until Platform participated in a performance and seminar event organised by Alan Read at the LSE in 2002 called Civic Centre. From then on we became allies and you wrote about Platform’s work and participated in events such as a Gog & Magog performance in 2004 and the launch of the Remember Saro Wiwa Living Memorial at City Hall in 2006 with Ken Wiwa, Angela Davies and Ken Livingstone. Indeed, it was typical that you were the one who built the link between us and the then Mayor of London. Later it was through you that we were invited to contribute to the Kilburn Manifesto, a commission that resulted in Platform’s collective essay ‘Energy Beyond Neoliberalism’ which has become a foundation stone for our ongoing work. You have been such a generous ally, and knowing that you are there wishing us well gives us strength and comfort.

You and I began to meet for dinner at Small & Beautiful, a restaurant near your flat in Kilburn, in January 2008 and we continued to do so now and then for the next seven years, with increasing regularity. We talked of everything from class to bird watching, from the Faroe Islands to the Tories.

Of course there was so much that we did not get to. I do not know if you were baptised, or whether your parents were church-going. I imagine that like me, you were ‘ethically, culturally Christian’ but that you lived your days outside the light or shadow of Christ. For me the spirit realm exists in the life world of animals and plants, in mountains and oceans. Your love of birds was intimate enough that surely you too had experienced that moment when, after many years of looking at another species, you were aware that they were looking back at you. The owl turns its head and for what seems like an eon it stares directly at your open mouth. It scrutinises you. It asks who are you? What are you doing? Why are you here?

I’m looking at what I think was the last postcard you sent to me. It shows a volcanic eruption at the Krafia Fissure in Iceland, an orange burning gash in the grey wasteland. On the reverse you wrote:

“The planet ‘blowing a gasket’? I love this place – it’s the line of fracture where EurAsia and the Americas are most clearly moving apart”

Here is the Earth undergoing its changes with immense energy, regardless of humanity. (How you love migrant rocks).

So what do you think about the political eruptions of the present times? From you I’ve learnt of the idea and the language of ‘settlements’. Of the notion of the social democratic realm and its destruction by the Right giving birth to the ‘neoliberal settlement’. We have talked at length about the question as to whether the neoliberal settlement is closing and a new realm is being born. The evidence for this has been gathering since you passed: now comment pieces everywhere talk of the ‘death of neoliberalism’ and the ‘end of globalisation’.

You witnessed, and wrote about with immense clarity, the destruction of the industrial zones of social democratic Britain and the evolution of the city of globalisation. How then to interpret the shifts that we see around us now in terms of geography? It is potent just how much the politics of the Right are expressed through symbols of space, through the definition of space, from the deportation of ‘migrants’ and the calls to tighten the UK’s borders, to the icon of Trump’s ‘Mexican Wall’. The current battles between political visions are not only fought over race and faith, but also over space.

It is good to talk with you right now about this. Almost all that I learnt from you I learnt via conversation. I confess that I’m a slow reader and I have not read all the books of yours that I should have. Not yet.

Many is the time in conversation that you’ve insisted that a settlement determines not only the political and economic structures but also the way we are. That a person living in 1950s Britain, was a quite different type of person to one living here in the 2000s. Who we are changes as the settlements shift. What then of the nature of the person that is now being formed as the settlement shifts out of neoliberalism into something different? Who are we becoming? Trump, and a number of others that play similar roles, appear to value brazen egoism, ruthlessness and a disdain for moderation over and above notions of truthfulness or respect. And they are profoundly anti-egalitarian. Is this a model of the future? Is this how we are becoming? Or is this the thing that we are fighting against, the shadow to a possible light?

You have always been a fighter. Even in the weeks before you passed you were busy with talks and meetings, papers and articles. Your work has taken place in dialogue, in the heady back and forth of discussion. And you have never given up, despite the political set backs of Britain in the 1980s and the dwindling of the Left in Latin America more recently. You’ve always thrown yourself into the throng, never retreated into cynicism or nostalgia. It seems you were always looking forward. So I’ve no doubt that you are looking forward now.

The passing of your body does not mean the passing of your imagination. It would be a grave error of mine to think that I cannot learn from you now in the way that I have done over meals in that Kilburn restaurant. Of course I can gain insight from looking at the world through the lenses that you ground.

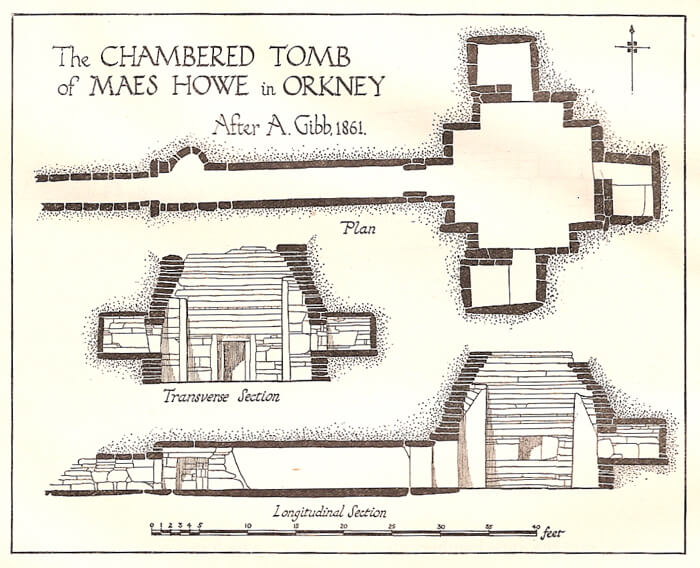

Several years back Jane and I went to see Maes Howe, the Neolithic tomb on Orkney. I’m sure you visited it too and would remember how in order to gain entrance you stoop along a narrow passageway. After several yards, you stand upright and find yourself in a stone chamber. In each direction there are stone shelves in the alcoves. It is said that when the tomb was in use the bones of the dead would be placed on these shelves. That the living would stand in the chamber and look upon the skulls of their forebears, perhaps some of whom they’d known, and see them at eye level.

Nearby, in the room where I am working, there are shelves with copies of your books upon them. They are at eye level. Your lines of thought are present to me. You built a palace of ideas, a people’s palace with many doors and no guards, and I am fortunate to be one of thousands who find shelter inside it. You may only be phosphate of calcium but your ideas are singing.

I need to linger a while in that palace, to sit in seclusion with your writings. I’m sometimes plagued by regret that I did not meet you more times in that Kilburn restaurant. That I missed out. Perhaps I can overcome that feeling by giving my time in your absence to make you present? What luck to have your words held in your books. Now I can pick them up again and be able to carry on this conversation, trying to interpret the nature of these turbulent times.

With thanks to Jane Trowell & Anna Markova

An earlier version of some of this text can be found in ‘Cultural Studies’ – journal ISSN 1466-4348

[1] Sylvia Plath – ‘Contusion’ – 1965 – in ‘The Collected Poems’ – Harper Classics – 2008

[2] John Berger – And our faces, my heart, brief as photos – Writers and Readers – 1984 – p101