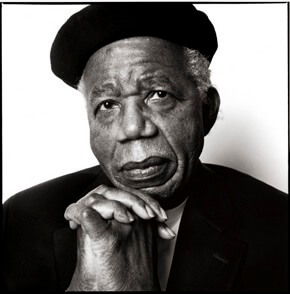

Nigerian write Chinua Achebe died last Thursday at the age of 83. He is a key figure in world literature and a writer who along with others utterly changed the way cultures pre- and post-imperialism – and pre-missionary – imagined representing themselves. In so doing, he bolstered the challenge to western and white supremacist thinking, and at the same time laid the ground for a heavy critique of the way many do-gooding western-based charities and activists frame their activities in places such as Africa. Not that that work is done, unfortunately.

Nigerian write Chinua Achebe died last Thursday at the age of 83. He is a key figure in world literature and a writer who along with others utterly changed the way cultures pre- and post-imperialism – and pre-missionary – imagined representing themselves. In so doing, he bolstered the challenge to western and white supremacist thinking, and at the same time laid the ground for a heavy critique of the way many do-gooding western-based charities and activists frame their activities in places such as Africa. Not that that work is done, unfortunately.

The breathtaking novel ‘Things Fall Apart’ (1958) binds the reader completely into the lives, struggles and dramas of neighbouring villages, each with their cultures, hierarchies and power struggles. By doing this so effectively in the first half of the novel, the shock of the arrival of white missionaries is felt at a gut level. As in the best art, the reader sees the world through new eyes, and nothing is the same again.

For Platform’s campaigning on oil and justice in Nigeria, the key inspiration here is that Achebe, along with Wole Soyinka, Buchi Emecheta, Amos Tutuola, Chinweizu, and Ken Saro-Wiwa, was of a generation of writer-activists who each in their own way re-framed and re-centered the way stories of their part of Africa are told, and succeeded in getting heard by those who did not want to hear them. They created a blistering critique of how legacies of Britain’s former (mis)rule have played out into the racialised factionalism, normalisation of corruption and exploitation that Nigeria now grapples with. As writers involved in struggle, they also put their lives on the line for it.

Achebe and Soyinka’s work has also provoked controversy. Some Afrikanists perceive such writers to utilise a European-influenced literary style, directed mainly to intervene in those audiences. Writing in English at all is seen as politically problematic for some such as Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Buchi Emecheta’s extraordinary output intervened on all sorts of levels, notably in gender politics, demanding a vivid space where women’s experience is assumed as equal. Tutuola’s fascinations with the richness and poetics of Yoruba folktales brought these compelling stories to a new audience. Chinweizu’s scholarly activism helped theorise resistance and resilience in the face of overwhelming inequalities. ‘The West and the Rest of Us’ is a searing classic.

Saro-Wiwa exploited everyday street language and patois to reach the audiences that most interested him – Nigerians and West Africans. He did this most famously in his novel ‘Sozaboy’, and the very popular TV comedy satire ‘Basi & Co’, which ran to hundreds of episodes and was loved nationally. At the same time, Saro-Wiwa used the perceived high status of formal English to intervene in dominant cultures – his essays, interviews attest to that tactic. Soyinka and Saro-Wiwa famously disagreed over the politics of literary style, but this did not take away from the solidarity on the politics of oil, Nigerian state corruption, and post-colonial legacies.

Saro-Wiwa exploited everyday street language and patois to reach the audiences that most interested him – Nigerians and West Africans. He did this most famously in his novel ‘Sozaboy’, and the very popular TV comedy satire ‘Basi & Co’, which ran to hundreds of episodes and was loved nationally. At the same time, Saro-Wiwa used the perceived high status of formal English to intervene in dominant cultures – his essays, interviews attest to that tactic. Soyinka and Saro-Wiwa famously disagreed over the politics of literary style, but this did not take away from the solidarity on the politics of oil, Nigerian state corruption, and post-colonial legacies.

And underneath all of this, flowed and still flows the uncontainable genius and legacies of Fela Kuti – as musician, activists, poet, lover, legend.

The current generation of writers including Helon Habila, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and recently Ken’s daughter Noo Saro-Wiwa take us to new understandings: Habila’s 2010 novel ‘Oil on Water’ is a gripping account of how the oil industry and the politic of oil plays out in small communities in the Niger Delta.

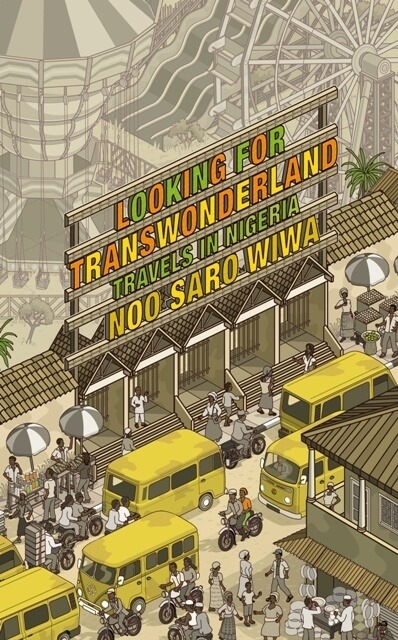

Adichie has hooked us on narratives of Nigeria that weave in the intellectual and political life in universities in the 1960s with village realities now, the unspeakable brutality of Biafra with how religion can oppressively play out in families. The very beauty of her writing draws us to places we didn’t know we wanted to go. Noo Saro-Wiwa’s 2012 book ‘Looking for Transwonderland’ takes the reader on a fascinating road trip around present day Nigeria as Zina tries to find her way to relate to the country which has shaped her life so profoundly, while growing up in Britain.

Adichie has hooked us on narratives of Nigeria that weave in the intellectual and political life in universities in the 1960s with village realities now, the unspeakable brutality of Biafra with how religion can oppressively play out in families. The very beauty of her writing draws us to places we didn’t know we wanted to go. Noo Saro-Wiwa’s 2012 book ‘Looking for Transwonderland’ takes the reader on a fascinating road trip around present day Nigeria as Zina tries to find her way to relate to the country which has shaped her life so profoundly, while growing up in Britain.

Thinking about diaspora, Scottish-born poet and writer Jackie Kay’s moving and insightful memoir ‘Red Dust Road’ investigates her courageous journey to find her Nigerian father, and to connect to her Nigerian heritage. Her white Scottish mother had conceived Jackie in a short-lived encounter with a Nigerian research student, and Jackie was put up for adoption. She was lucky to be adopted by parents whom she adored and who adored and supported her. Her brave, vulnerable and startling journey between the UK and Nigeria makes bridges – not only between her and her past, but between us – the readers – to a whole world of complex understandings about belonging, love, race, loyalties, differences and intimacies.

It is difficult to speak of ‘Nigeria’ without also remembering that its boundaries were artificially constructed by British colonialism, which ruled by pitting people from various language groups, traditions and religions against one another – laying the basis, and often stoking future conflict. While the Nigerian people still face – or in the case of the Nigerian state, deliberately fails to face – the task of trying to make Africa’s most populous nation cohere democratically, it is the writers, poets, musicians, there and elsewhere who can most audibly speak truth to power. Achebe was not the first, but his passing marks a moment to take stock of how artists can succeed in changing the stories we tell ourselves, and in changing the ‘truth’.

Soyinka wrote in his Nobel Laureate lecture 1986 about what was available in libraries across the former colonised countries of Africa: “…the libraries remain unpurged, so that new generations freely browse through the words of Frobenius, of Hume, Hegel, or Montesquieu and others without first encountering, freshly stamped on the flyleaf: WARNING! THIS WORK IS DANGEROUS FOR YOUR SELF-ESTEEM.*”

As colleague Selina Nwulu comments: “I think Soyinka’s quote from ’86 is an important one. One thing I’ve noticed is that to be ‘educated’ was, (and to a certain degree still is) to read the western intellectuals, and therefore to conform to westernised ways of thinking about and understanding race. I remember in doing some reading on Achebe, he mentioned the fact that when he started reading some of the literary greats at university, he started to hate himself because of how ‘he’ was portrayed in literature and therefore how he was made to identify with himself…all very Fanon-esque**. So I think ideas of self- hate – and Achebe being amongst the wave of writers/activists to transcend this – and the frameworks of how to educate and be educated is important (if still very complex).

It is doubtful how much the official libraries across Africa have changed, but the rise and rise of writers such as Habila and Adichie, and Kay is a sustained confrontations with this dangerous stagnation. If the previous generations’ work and activism blasted open doors, this generation is taking off the hinges. All have changed the past, present, and future. As African-American activist Angela Davis put it: “We should think about the role of art in the creation of historical memory – how artists can enrich our understanding of the past and the present and push us towards a better future. Artists can encourage us to dream in a radically different way.”***

It is doubtful how much the official libraries across Africa have changed, but the rise and rise of writers such as Habila and Adichie, and Kay is a sustained confrontations with this dangerous stagnation. If the previous generations’ work and activism blasted open doors, this generation is taking off the hinges. All have changed the past, present, and future. As African-American activist Angela Davis put it: “We should think about the role of art in the creation of historical memory – how artists can enrich our understanding of the past and the present and push us towards a better future. Artists can encourage us to dream in a radically different way.”***

—–

* from ‘Wole Soyinka: an appraisal’ edited by Adewale Maja-Pearce.

** Martiniquian writer and activist Franz Fanon (b 1925) published ‘Black Skin, White Mask’ in 1952, six years before Achebe’s ‘Things Fall Apart’.

*** full transcript of Angela’s speech here.

Note: Helon Habila spoke at the launch of Platform’s ‘Remember Saro-Wiwa’ campaign at London’s City Hall in March 2005.

Wole Soyinka spoke alongside Maria Saro-Wiwa and others at the ‘Remember Saro-Wiwa’ commemoration, which on November 10th 2005 marked 10 years since the executions of Ken Saro-Wiwa and nine Ogoni activists by the then Nigerian military government, with the collusion of Shell.

Angela Davis was headline speaker at the launch of Platform’s Living Memorial to Ken Saro-Wiwa – the Battle Bus – by Sokari Douglas Camp, 10th November 2006.

For more on the Battle Bus, go here

The Bus is currently in residence at Bernie Grant Arts Centre, Tottenham.