Global Frackdown 2 will be taking place on Saturday 19th October. It is an initiative that is aiming to bring together community actions from all over the world to challenge hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, so we thought it would be good to hear from someone in Algeria about the situation there.

Algeria has made some amendments to its hydrocarbon law in January 2013 to open the way for exploiting unconventional energy resources. According the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Algeria holds the third largest recoverable shale gas reserves after China and Argentina. Already, Eni, Shell and ExxonMobil have held talks with the national oil company Sonatrach about shale gas extraction, despite the enormous environmental impact it could have on the Sahara.

unconventional energy resources. According the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Algeria holds the third largest recoverable shale gas reserves after China and Argentina. Already, Eni, Shell and ExxonMobil have held talks with the national oil company Sonatrach about shale gas extraction, despite the enormous environmental impact it could have on the Sahara.

Groups inside Algeria such as the Collectif National pour les Libertes Citoyennes (CNLC) are challenging the fracking plans. They have researched the the problems surrounding shale gas production and publicly challenged corporate plans through the media and at international events, including the recent World Social Forum in Tunis. Mehdi Bsikri, a journalist and member of CNLC kindly agreed to answer some of our questions.

Why is it the case that countries such as Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia are planning to exploit shale gas and oil projects?

With regards to Algeria, state officials, especially the Prime Minister and the Minister of Energy and Mines, advance arguments that have not been debated in the public sphere. They claim that Algeria has the third largest reserve of shale gas in the world, referring to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) report. They also back their arguments by the probability of decreasing supply of hydrocarbons in Algeria, and according to them; only shale gas could replace conventional energy. However, some observers have commented that the Algerian government has the restricted vision of a regime lacking legitimacy, and is only seeking a new rent to perpetuate its grip on power.

At a time when fracking has been banned in France and it has become increasingly controversial in the UK, it seems that countries of the Maghreb are being put under pressure from multinationals and Western capitals in order to secure access to energy. What are your thoughts on this?

Civil society in the West has forced some governments to ban fracking, the only process to extract shale gas. But these governments do not hesitate to go to countries in the south such as Algeria to exploit it. Marketing conferences are being organised to promote shale gas, as was the case at Hilton, Algiers in November 2012 and September 2013. Multinationals encourage Southern countries to exploit shale gas while hiding the negative consequences on the economy and the environment. In any case, if there is a catastrophe, they will leave without paying compensation because national companies such as Sonatrach will be in charge of transport and finances.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that Algeria possesses very important reserves of shale gas. Is that true? Has the exploitation already started in Algeria?

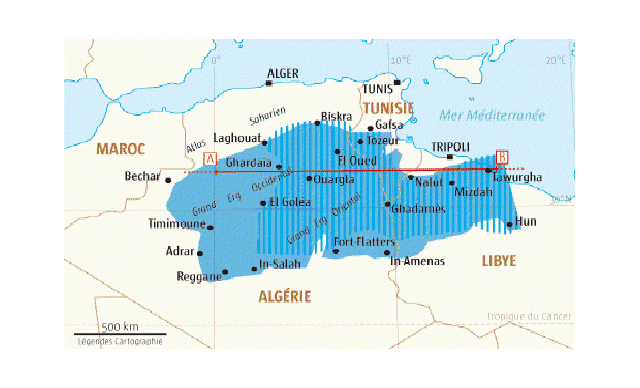

The last report of the EIA dates back to 2004 according to Professor Chems Eddine Chitour, the director of the fossil fuel energy laboratory at the Polytechnic Institute in Algiers. He argues that the 2013 report is no more than a copy of the 2004 version. Moreover, we don’t know in which zone or in which basin these surveying works have been conducted. The exploitation has not started yet. Today, Total and Schlumberger operate exploration projects in the region of In Salah, specifically in Ahnet 1 and Ahnet 2 basins.

What environmental and economic risks are the Maghreb countries are facing if they start exploiting these unconventional resources?

Algeria possesses around 60,000 billion m3 of fresh water with low salt content. The use of more than 500 chemicals in the process of hydraulic fracturing seriously threatens water tables, because the wells that will be drilled will cross these water layers. Moreover, the Algerian water basins are inter-connected. Therefore, if you pollute at In Salah, the chemical substances that penetrate the water will spread and reach even Ouargla and Biskra (600 to 900 km away respectively), giving rise to other risks. The agricultural regions in southern Algeria, such as palm groves, will be destroyed. This will create further poverty and force people to migrate.

The risk to the national economy is huge. The exploitation of shale gas doesn’t guarantee any profitability. Currently, the gas world market is dominated by spot contracts (free markets) while Algeria has always relied on long-term contracts. Thus, investing billions of dollars, producing quantities that won’t exceed 40% of reserves, and selling them at prices that vary between 3 and 5 dollars/BTU could lead the country to the verge of bankruptcy.

Why not invest in renewables given the significant potential these countries have?

The Algerian regime does not have a long-term vision. And honestly, it doesn’t have a short-term one either. It rules the country in an archaic and obsolete manner. There is no plan or perspective for the development of renewable energy. The very few declarations regarding green energy are mere populism. What matters for the system is to perpetuate itself whatever the cost.

Facing this big challenge, what is the Algerian civil society doing to resist the march towards shale gas exploitation? Is it a fait accompli?

No, there is no such thing as a fait accompli. Our obligation is to not stand by and remain silent. Algerian civil society focuses its struggle on liberties, which is very noble in itself. But as the subject of shale gas exploitation is technical, there is a kind of lack of interest or rather no adequate awareness about it yet. The absence of a public debate maintains the vagueness and confusion. The CNLC (Collectif National pour Libertes Citoyennes) has done everything it can to put the debate in the public sphere. We have achieved some positive points thanks to the activation of our media network. It is a small experience but it’s only the start.