This Wednesday a Dutch court will rule on whether Shell should clean up oil damage that destroyed a group of Nigerian farmers’ land in a landmark case that could lead the way for a spate of similar actions in the future.

This Wednesday a Dutch court will rule on whether Shell should clean up oil damage that destroyed a group of Nigerian farmers’ land in a landmark case that could lead the way for a spate of similar actions in the future.

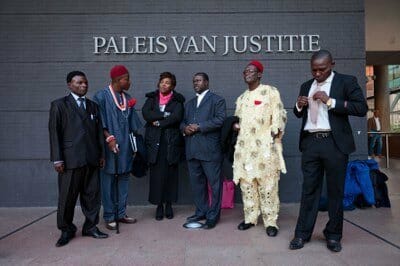

The farmers, whose land has been destroyed by oil from Shell pipelines, have travelled to Europe to demand justice, where Shell’s headquarters are comfortably insulated from the polluted and militarised wastelands of the Niger Delta. The farmers have been working with the Dutch organisation Milieudefensie in bringing the claim.

Legal cases outside of Nigeria are the latest front in the battle for environmental justice in the Niger Delta. The region is an important wetland and coastal marine ecosystem and is home to some 31 million people many of whom rely on it for their livelihoods. The oil and gas industry has profited from plundering its resources but has brought conflict, poverty and pollution to the region.

The stranglehold of oil companies dates back to the time when Nigeria was a British colony. Shell gained its monopoly over Nigerian oil in a joint venture with BP by the arrangement of the British Government. Nigeria won independence in 1960, but decisions about Nigeria’s future are still made far away in Shell’s offices in Europe. Those fighting for justice have now turned these power relationships on their head and are following the flow of oil and power to hold companies like Shell to account in courts in Europe and the US.

This trend has happened for a number of reasons. When cases have been successfully brought against oil companies in Nigeria, the under-resourced courts struggle to implement decisions such as collecting compensation and clearing up spills, and there is a cap on compensation for victims. Oil companies have then tied up communities in lengthy and costly appeals.

A similar case is underway in the UK. Residents of the town of Bodo in Rivers State are taking legal action against Shell over pollution from two major spills said to be equivalent in size to the Deep Water Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Shell tried to buy off the 49,000 residents with a payout of £3,500 and some bags of materials such as rice, beans and sugar.

The Supreme Court in the US is also considering a lawsuit accusing Shell of complicity in the murder and torture of Nigerian activists. This is another landmark case that could decide whether survivors of human rights violations in foreign countries can bring lawsuits against corporations in U.S. courts.

If these cases succeed then many other will follow, leaving Shell exposed to an unprecedented mass of potential litigation and liabilities. But will this threat be significant enough to push Shell to change? The jury is still out but while it is, and while we have a hope, the fight goes on.