Everywhere is the city. And everywhere is not the city.

A small congregation, just a dozen of us, are guided in careful-footed silence along the central path through the cathedral of Russia Dock Woodland in London’s former Docklands. It is 04.30 am on 5th May. Our guides, John Cadera and Richard Page-Jones, draw our attention to the calls of Blackcaps, Wrens, Blackbirds, Robins and Great Tits. There is a gentle atmosphere of quiet reverence on this Dawn Chorus Walk around the woods and ponds of the old Surrey Commercial Docks.

I am struck by how the walk reminds me of a religious service. We the attendees are expected to be quiet. John and Richard, binoculars denoting their office, are the priests, intercessors between us and the birds. They interpret, they explain, they guide us through the time they have been allotted. And we? We pay attention. We put aside our daily cares and attend to the world around us, to these companion species, to ‘Nature.’

The walk is part of Soundcamp 2019, the sixth in a series of extraordinary twenty-four hour long art & nature events, held with Stave Hill Ecological Park, London. The heart of the festival is a day spent listening to creatures of the Earth through a continuous dawn chorus. Around the globe are at least 75 participating groups – ranging from individual ‘streamers’, to a cluster of ‘amateurs’ or a university research project – who ‘live stream’ the sound of the dawn chorus as it begins to unfold in their woods or forest, their mountains or beaches. Sitting in The Shed at Stave Hill, Grant Smith, Maria Papadomanolaki and Hannah Kemp-Welch, co-ordinate the 24-hour broadcast on the internet, fading in a live stream from Queensland Australia as they fade out one from the foot of Mount Fuji in Japan, fading in Kathmandu as they fade out the sounds of dawn in Kolkata, India. And so on, hour after hour, as the sound moves around the Earth.

On the laptop screens arrayed on a table in The Shed, we see the locations of the different live streamers dotted around the Earth like stars in the firmament. The sound from each one floods into this small room as the suns rays opens up the day in Santiago, Chile or Tower Hamlets, London. The map on the screen shows a gently arcing band of darkness and light, this is the blissful curve of the sun’s light, the ‘grey line’ that comes just before the dawn and opens up this singing planet.

The event is titled ‘Reveil’ – meaning ‘wake up or alarm clock’ in French – but what is also taking place here is ‘reverie’, a reverie for the Earth. An extraordinary act of celebration, an act of listening to, paying attention to, a beautiful planet. And this ‘planet’ that is being listened to are the calls of birds and animals, the sounds of trees and insects, that are audible to the human ear. These are the songs of the ‘more-than-human’, the voices of our companion species, around the world who we co-inhabit the planet with on this day, in these hours. (Only occasionally are their voices disturbed by, or accompanied, by the low rumble of ships engines, the dull roar of road traffic or the distant drone of a jet.)

Soundcamp coordinates this global event, and central to the initiative are sound artists Grant Smith and Dawn Scarfe. Dawn researches and coordinates Reveil. This remarkable project is tracked across the globe not from some research lab or some arts centre, but from a gem of an ecological park in South London. Soundcamp’s Reveil is in itself a celebration of Stave Hill’s pioneering vision and extraordinary resilience as an urban nature refuge over many years.

In the UK of the late 1970s there was a growing movement for Urban Ecology, which lead to the Trust for Urban Ecology (TRUE), pioneered by Max Nicholson. This gathering of activists argued that ‘Nature’ should not be seen as existing solely in the realm beyond the metropolis, in the ‘Countryside’. But rather it does, and could, exist within the City. That although the urban environment is predominately the space of the human, we are not alone, that we live in these places together with a myriad of other species, from House Spiders to Wasps, from Carrion Crows to Blackbirds, from Plane Trees to Buddleia. That we should see these creatures not as encumbrances to be removed (witness the felling of trees in Sheffield or Walthamstow), nor as sources of anxiety or vectors of disease (as with House Spiders and Feral Pigeons), but these are fellow inhabitants of the city, fellow citizens, companion species and together we make this place that we call London.

Arising from this movement came initiatives for ecological parks, areas of land and water, woods and meadows, set aside to create havens for ‘wildlife’ as it was known then, but which forty years later we might now refer to (in the shadow of the thinker Donna Haraway) as the ‘more-than-human’.

The first park was established in 1976 by TRUE on the land of former dockside next to Tower Bridge and was named ‘William Curtis Ecological Park’ after the 18th London botanist William Curtis. The area of a few acres combined ponds and reed beds, grass meadow and some young trees. But it did not last long. The land once owned by the Port of London Authority, came under the control of the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) when it was established by Thatcher’s Conservative Government in 1981, and directly managed by the Minister for the Environment, Michael Hesseltine MP.

The park was closed down in 1985 and when Platform came to be based around the corner at 7 Horselydown Lane five years later, I remember it as an area of ‘wasteland’ hidden behind plywood hoardings and beloved by Foxes. Now the land is the site of the GLA’s City Hall, the Bridge Theatre and a block of many stories of luxury flats. The land itself, and the whole of London Bridge City stretching between Tower Bridge and London Bridge, is now in the ownership of St Martins Property Group, an arm of the Kuwait Investment Authority, the sovereign wealth fund of Kuwait. Oil underpinned the ‘development’ of this land and the owners of that oil-derived capital now generate returns on it through rental. Land which had been abandoned by capital, disregarded as ‘wasteland’ that could be set aside for an ecological park, was now a generator of returns and had ‘value’, indeed today it is said to be some of the most ‘valuable’ real estate in the world.

But all was not lost. TRUE cut a deal with LDDC, and in early 1984 the latter gave over another area of ‘wasteland’ on the site of the former Russia Dock in Surrey Commercial Docks near Rotherhithe. Here was established the Stave Hill Ecological Park. The ‘gift’ of this land by the LDDC took place in the midst of a ferocious battle between the Development Corporation and the communities that were long established throughout the docklands, central among those campaigning against LDDC was the Docklands Community Poster Project, driven by Loraine Leeson and Peter Dunn and involving others such as the artist Sonia Boyce. The powerful resistance doubtless encouraged the LDDC to set aside at least some things for the local community, amenities such as the land for the ecological park. (During Soundcamp, Charlie Fox of Inspiral London created a walk from William Curtis Park to Stave Hill, taking attendees through the streets of South London.)

Four years later Platform sited ‘The Tree of Life, City of Life’ Tent on Greenland Dock only five minutes walk from the Ecological Park. John Jordan, Jens Storch, Ana Sarginson, Pete Durgerian and myself all worked around the tent and across the neighbouring area for two weeks as we endeavoured to explore the ‘metabolism of the city’, inspired by a concept evolved by Herbert Girardet. We were visited by some other members of the project team, which included Herbert, Rodney Mace, Teresa Hayter and Nick Robins. On one if these visits Rodney was interviewed on the top of Stave Hill and as he discussed the past and future of the area Pete’s camera panned over the saplings and scrub that covered the infant ecological park, the dock-infill of rubble that had been landscaped and handed over to TRUE.

Now, thirty years on, the Tent returned to the area, invited by Soundcamp 2019 to pitch at Stave Hill Ecological Park (now run by TCV) and hold an intergenerational discussion between three original participants Herbert Girardet, myself, John Jordan, with two younger interlocutors Will Essilfie and Hajra Gulamrassul. The aim was to make a place to reflect on what has happened in the past thirty years and what might happen in the next thirty, to reflect on the period 1989 to 2049.

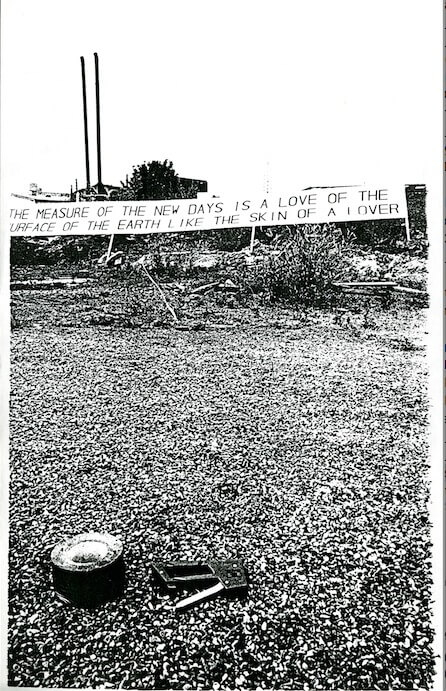

Among the audience tightly packed into the Tent, was Jessie Brennan who had also been commissioned by Soundcamp 2019 to produce an artwork. Jessie’s piece was in two parts, one a sound installation in London Bridge Station and the other on the crest of Stave Hill. This latter, an artificial mound, created by the LDDC in the early 1980s, overlooks the Surrey Docks area. (It was from here that Rodney had looked out across the fledgling ecological park.) Jessie had installed a billboard-sized blow up of a photo taken from Stave Hill in 1986 allowing the viewer today to juxtapose the image of bare earth and fences with the woodland that now covers the park.

The piece is, like the Soundcamp, a hymn of praise to the resilience of the ecological park. It has survived, it has resisted and survived. For the land all around has sky-rocketed in capital ‘value’, mirroring the rise in the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf just across the river on the Isle of Dogs. The park has been under constant pressure, from developers who want to obtain the site, and from others who’ve committed arson or stolen equipment from the park compound. But it has survived, and now it has official nature reserve status so its future is legally secure. Far more important it has survived because it has become loved by the community that lives around it, loved by children and parents, by dog walkers and volunteers, by those who look out for it, and by those that feel they ‘possess’ it and indeed are ‘possessed’ by it – including the organisers of Soundcamp. Without doubt fundamental to the park’s survival and flourishing, has been the indefatigable determination of its committed site warden, Rebeka Clark who has fought for and developed the project since the mid 1980s.

Its survival is all the more remarkable because it stands in the lee of Canary Wharf, in the shadow of one the most intense concentrations of finance capital on Earth. There is something hypnotic about the contrast between those well-known towers of glass and steel and the densely packed woodland of Alder, Hawthorn and other trees. These species seem to stand in defiance of the skyscrapers of corporate offices, these other species speak of an other way of being, they speak of another way in which the city could be.

The structures of Canary Wharf and the ceaseless building upon Docklands appears to drive out the other, drive out other species, and suggest that the city is a purely human space. However Stave Hill Ecological Park suggests that this is not the case, suggests that we can live with the other, we can live with other species, indeed the joy in our lives is enhanced when we do live in companion with other species. Soundcamp’s Reveil proclaims the same reality, that we live on this Earth with a multitude of other creatures and we can, and shall, revere them.

This way of being, distinct from the world described by Canary Wharf, becomes evermore important in the light of the UN Report of Biodiversity published on the 6th May 2019 and revealing that over 1 million species of plants and animals are threatened with extinction in the coming decades if we continue with ‘business as usual’, or rather continue to have business, or capital, determine what is a ‘usual’ way to live.

In the 1989 ‘Tree of Life’ project, the Tent had been located at the Mouth of the River Wandle in Wandsworth just prior to coming to Greenland Dock. There we had erected a banner, many meters long, across a stretch of ‘wasteland’ (or rather of land with little value to speculative capital). On the banner were the lines that seem as relevant as ever:

‘The Measure of the New Days is a Love of the Surface of the Earth like the skin of a Lover’

Thanks to Grant Smith, Dawn Scarfe, Rebeka Clark, Jessie Brennan, Charlie Fox, Jane Trowell