How can we use images to tell the stories we want to tell – and avoid repeating the ones we don’t?

Photo memes are fast becoming a viral hit. Quicker than 30 second videos, the combination of an image and a short piece of text is being used across social media to convey jokes or support ideas and arguments. Early designs that are still sucessful build on the classic cat genre, such as:

In fact the style is all but new, and seems to take inspiration from the work of Barbara Kruger (1945-), which makes political comment in a form reminiscent of advertising – and even includes the occasional kitten:

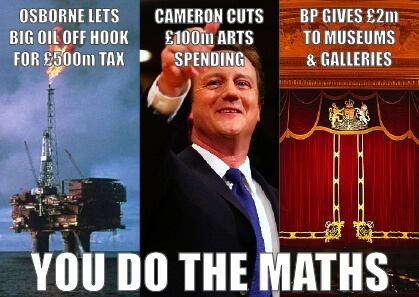

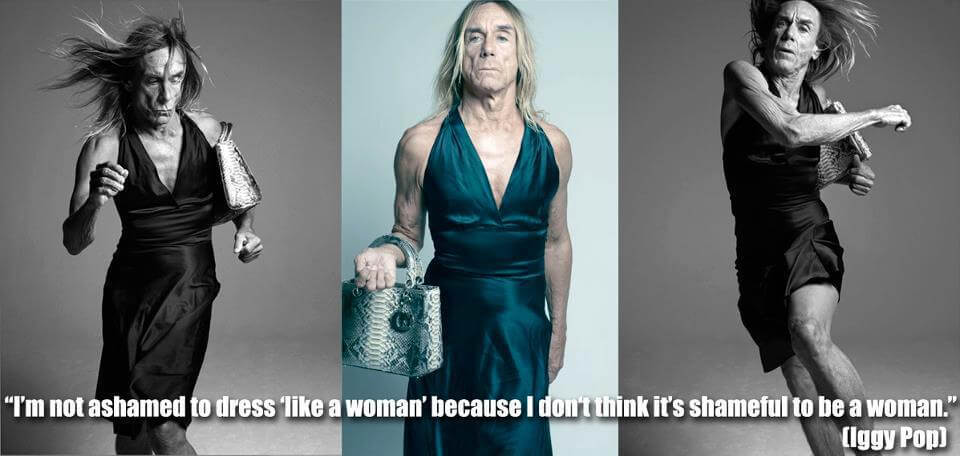

The potential of using Font: Impact and Outline: 2pt 100% black / drop shadow – or any other slap-dash layout choice – was quickly taken up by people wanting to deconstruct gender norms, put the expenses scandal in social context and more…

At Platform we looked for a way to use figures released in the press on how much the government was suggesting oil and gas companies operating in the North Sea simply not bother paying. We lined them up with arts cuts and oil sponsorship of the arts, creating a photo-meme that got shared over 2000 times on Facebook (lifetime ambition: tick)

Later that month, Platform released two briefings that revealed secret documents (leaked to us) that put a figure on Shell’s security spending and support of militant groups operating in the Niger Delta. The information was really important to share, but raised the question of how to visualise the story.

In a post-Kony2012gate-era any NGO based in the global north that does any work related to any country in Sub-Saharan Africa should be thinking deep and hard about not only messaging, but what those narratives say about their overall strategy. The Invisible Children promo video sought to raise money for the US-based NGO that in 2011 spent only 32% of its income on direct services, the rest on staff, travel and film production. This particular 10 minute super-high-budget short had barely a semblance of story-line with little actual information on it’s supposed subject war criminal Joseph Kony, offering instead a ‘white saviour’ narrative centred around company director Jason Russell and his son. It was brilliantly and thoroughly deconstructed in a wealth of blogs, articles and video respsones.

The global online confrontation of Invisible Children makes an important study of supposedly charitable projects re-inscribing racist tropes. Our friends over at SmartMeme have done fabulous work to develop practical methods for campaign groups to take a critical look at the stories they are telling in the campaign work they are doing. SmartMeme point to ways we can tell new stories to bring about changed realities. By asking what narratives a group’s work embraces and which it rejects, groups have found new ways to create effective strategy and more sound messaging.

In the case of Platform’s work on oil and the Niger Delta, the story we think is useful to tell is that while Shell says its ‘difficulties’ in Nigeria are all history, we can show that the companies human rights abuses are happening in the present. The report released last Autumn, Counting the Cost, documented human rights abuses between 2006-09 that Shell was involved in, the revelation of which directly countered the companies attempt to project itself as a ‘changed corporate figure’ in the region. The subject matter of one of the recent briefings’ revelations however, the financing of a militant groups who murdered 500 people in Warri, brings up difficult communications questions.

The question for us is, how do we tell that story with an image that doesn’t repeat problematic and racist tropes? Images that involve militant chic and bullet belt bling don’t tell a new story. The many images of weeks’ long protest against the oil industry in the Delta do tell stories of strength and resilience as opposed to victimhood or villainisation, but in this case we want to highlight the underhand role of Shell in creating chaos and hardship for communities.

We’re still thinking this through, so tell us what you think in the comments. And if you’re particularly driven on the issue, why not consider applying for our current vacancy ‘Oil & Human Rights Campaigner’?