Just over a week ago Tate Modern and its new landmark extension got a bit of a mauling from writer Will Self, who argued in the print version of The Guardian that it “symbolises the savage inequality of the capital”.

It’s an interesting piece about art, privilege and the hyper-rich, and has got people arguing on several fronts. But his powerful statement on inequality becomes even more potent when you take out the second ‘the’ to make it read ‘the savage inequality of capital’.

For while Tate still appears in most people’s eyes to be a public gallery, the role of private philanthropy, sponsorship and the art market is utterly critical to it, and some of us are worried that a loved institution is really going down a wrong path. This is not because Tate has been strong-armed to approach the private sector by an increasingly free-market-driven politics via recent governments and the DCMS. It is a wrong path because Tate itself appears to be actively driving this agenda by embracing the private sector to realise its grand projects such as the Turbine Hall commissions, the new extension etc. These eye-catching projects, their backers and the hospitality deals serve to secure Tate’s place at the top corporate table in a neoliberal and rapidly warming world. It’s not a table for the many. It’s a table for the elite few and has some worrying conditions attached to it.

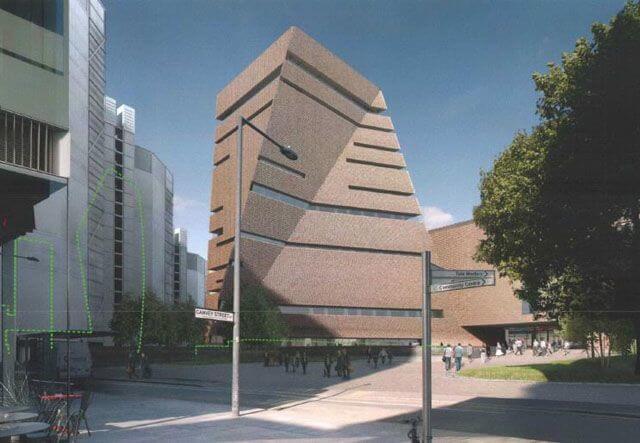

Let’s look at the new extension. Herzog and De Meuron’s building is a powerful statement indeed – it is a unique, arresting and high-spec, sustainable design that will contain two education and community outreach floors, a restaurant and cafe, shops, and four floors of new galleries mainly to enable Tate to show its new and growing collection of African and Asian contemporary art. It has cost upwards of £215m to build.

Yes, that’s £215 million bill for the extension.

Information in the public domain tells us that £50 million of the £215m is from the public purse, £7 million from the Greater London Authority, £5 million from the Wolfson Foundation and £10 million from the charitable foundation of Eyal Ofer, an Israeli philanthropist who made his fortune from shipping. The Financial Times goes on to tell us that the rest of the cash – a cool £143 million – has come from other private sources including the media executive Elisabeth Murdoch, banker John Studzinski, and one of Studzinski’s good friends, Tate’s Chair of Trustees and former Chief Executive of BP, Lord John Browne.

Let’s leave to one side whether we think London needs this new space when Tate Modern is already hoovering up a whopping 5.9 million visitors a year, more than twice the number that Museum of Modern Art, New York attracts. (Where else might benefit from tourists and visitors interest, time, and money if they were not drawn to Tate Modern’s galleries, shops and cafes? What’s the connection between Tate’s commitment to environmental sustainability and tourists flying in expressly to see their extraordinary building?)

Let’s leave to one side the Eurocentric history of collecting that leaves Tate only relatively recently trying to correct the picture by avidly buying up work from Asian and African artists (whose work, one may assume, needs to fit a certain notion of what art is, as determined by art critics and writers influenced by Western, European criticism and global art market values. Plus, why can’t they just sell off 10,000s of indifferent work by white European males to make space and cash for work by the systemically under-represented: women, people of colour, and non-art-marketable art?).

Let’s leave to one side the ego, ethics and ecology of building these landmark edifices that are incredibly costly to build and maintain, designed to function as spectacle and an ostentatious display of wealth in a city that already proliferates in great and free art in interesting small and medium-scale venues. (What about Tate not following the route of the Guggenheim and Louvre by promoting art biodiversity rather than its ‘brand’.)

Yes, putting all that to one side, what on earth is really going on at the heart of Tate’s financial values where sums as big as £215 million are put against Tate’s fierce privacy over its modest BP sponsorship? Why is Tate going to the time and expense of fighting an Information Tribunal on how much sponsorship BP gives them, when the sum under examination is a paltry £10 million between four institutions over 5 years – Tate, British Museum, Royal Opera House, and the National Portrait Gallery.

If you divvy it up equally that’s £500k each a year from BP.

Could it be that the real stakes here are that Lord John Browne, Chair of Tate Trustees, ex-CEO of BP, Partner in Riverstone Holdings which owns Cuadrilla – a highly criticised fracking company – is such a major asset in raising cash for the new expensive extension and other ambitious schemes, that nothing is allowed to upset him. For John Browne is not only a patron of the arts and has given personally to the extension, but as we’ve already seen from his friendship with super-rich philanthropist John Studzinski he is supremely well-connected in the arts and in business. His friends and associates include those with stratospheric levels of wealth. And most of that comes from his lifelong professional networks within the fossil fuel industry.

One example: two years ago he started a joint oil and gas investment fund L1 Energy with Russian oligarch German Khan. Mr Khan and his L1 Energy partner Mikhail Fridman are together worth £10.5 billion. This is the kind of wealthy company Browne keeps, and the kind of influence he can access, and the kind of backers he can introduce to Nicholas Serota and the other Directors of major art institutions with whom he is friends.

Browne’s own net worth is hard to establish, but a small indication is given by estimates about his pay-off from BP in 2007. These vary from between £30million and £72million. That’s just his BP payoff, not his savings, salary and investments over his 40-year rise within BP, nor his current earnings from various directorships, nor his assets, properties, and tax breaks. Browne, Khan and Fridman are just some of Will Self’s ‘hyper-rich’.

So, these are yet more reasons why Tate continues its relationship with disgraced oil company BP, and is spending precious time and core costs on fighting court cases for a seemingly paltry amount relative to its overall turnover.

And this is why in the recent Information Tribunal hearing, Tate’s ‘Head of Legal’ Richard Aydon answered as he did when asked how Browne was deemed to be the official ‘qualified person’ to comment on disclosure of information about BP’s sponsorship of Tate: “Lord Browne was asked about this and he said he felt he was qualified to be the ‘qualified person’.” But of course he does.

It’s not the actual BP sponsorship of Tate Britain’s rotating collections and education programme that Tate is defending. This is a tiny detail, a smokescreen of ‘good works’. What’s at stake here in this neoliberal world of private-public funding is the race for the “savage inequality of capital”. From Tate’s perspective, being part of the networks which include the likes of Lord John Browne ensures access to influence and capital, for the small price of some reputational damage over environmental and human rights impacts of oil companies. The fact that Browne and his networks are also making astronomical profits from pulling oil and gas out of the ground – from driving climate change and climate injustice – is another damning association that our Tate should pull away from.

We want a Tate that is better than this. And we’re going to get it too.

It’s only a matter of time before a savage desire for equality takes hold and imagines a Tate without an oiled boys network, a Tate that encourages an art biodiversity, a Tate that is moving away from a carbon economy, and is sharing its pulling power to encourage audiences to move around the capital (and move the capital around) and to venture into the rest of this country exploring and discovering art by diverse makers in fascinating and fertile places outside Tate and London’s borders.