Today we’re in court with Tate over a long running struggle to get them to say just how much sponsorship money they’re getting from BP. Working alongside Freedom of Information specialists Request Initiative, we’ve put a lot of time and energy in to trying to find out this figure, and this is why it’s important.

Typical discussion with a random person about oil sponsorship of the arts:

Person A > Don’t you think it’s a bit concerning that we’re allowing some of the most destructive, climate-trashing companies on the planet to make themselves look respectable by buddying up with some of most cherished cultural institutions?

Person B > I hate what Shell and BP are doing to the planet, but isn’t it important too that these art galleries stay free to everyone?

There’s a widespread assumption, and it’s a very convenient assumption for BP, that it’s only by virtue of the massive amounts of cash that BP is pumping in to the likes of Tate that galleries are able to stay open and free to the public.

It’s just not true!

For one thing, one of the stipulations for the massive amounts of public money that these galleries get is that they stay free to the public. It’s our tax money that keeps Tate free, not BP’s. It’s also stipulated that that they have to find money from other sources – but it doesn’t have to be oil money.

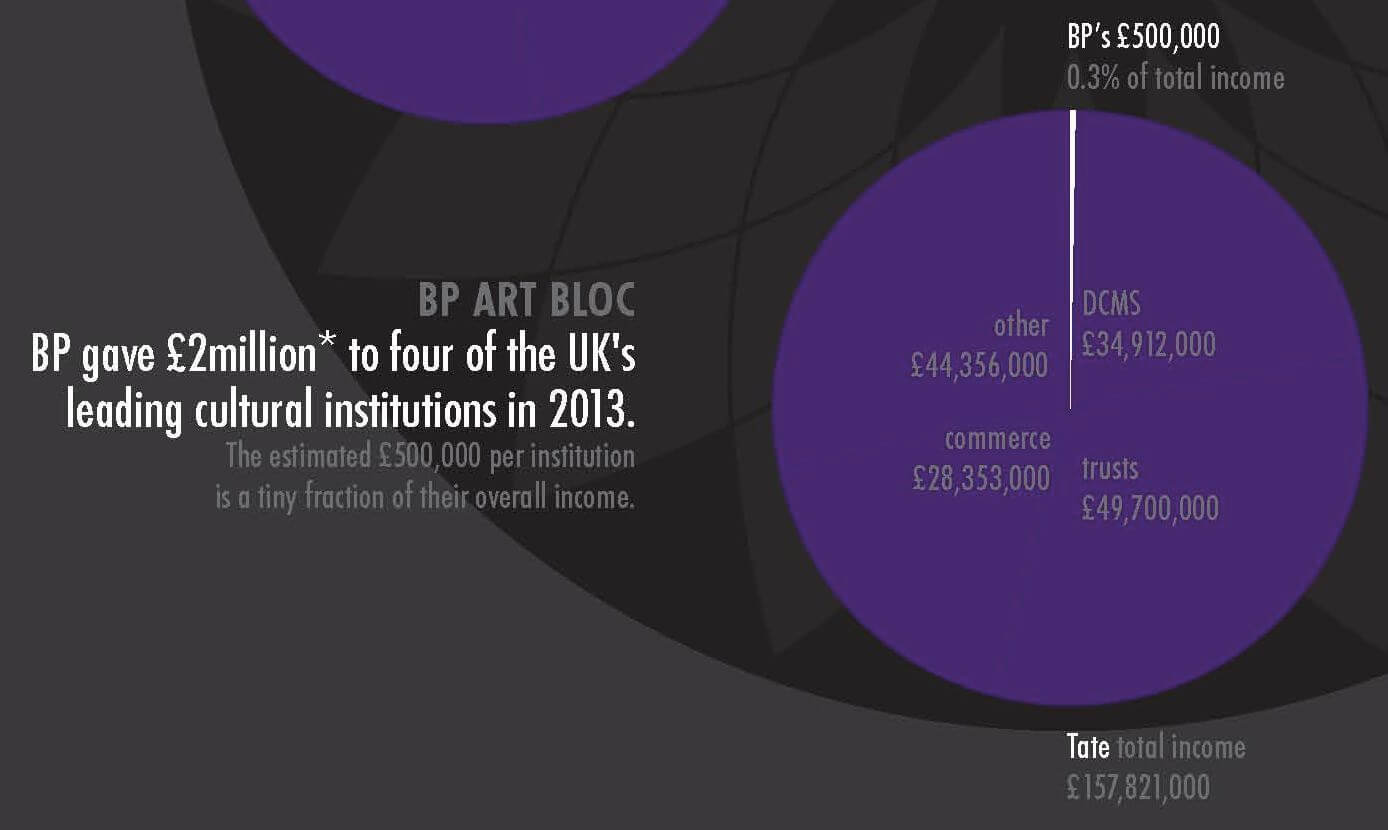

Secondly, the amount of money that we think Tate is getting from BP is so small in comparison to their overall budget that it would be entirely possible for Tate to adjust to not taking it without negative consequences for art lovers. According to the information that is publicly available, we think that BP’s money represents less than half a percent of Tate’s total income.

Secondly, the amount of money that we think Tate is getting from BP is so small in comparison to their overall budget that it would be entirely possible for Tate to adjust to not taking it without negative consequences for art lovers. According to the information that is publicly available, we think that BP’s money represents less than half a percent of Tate’s total income.

Tate’s argument is that it can’t reveal the information as it would be harmful to its commercial interests – that if it revealed this information now, it would harm the value of other sponsorship deals in future.

It’s funny though because other cultural institutions don’t think that.

In response to a 2008 FOIA request, the Natural Portrait Gallery disclosed that BP had donated £1.25m in sponsorship between 2003 and 2008; it disclosed this information within a month of the initial request.

The Science Museum, in response to a 2009 FOIA request about the museum’s sponsorship from BP and Shell, revealed the amounts donated for specific projects.

The Natural History Museum has responded to three FOIA requests in relation to sponsorship. It disclosed that it received £750,000 over two years from Shell for the Museum’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition. It also disclosed that it received £250,000 from Anglo American in 2006 for development of the Darwin Centre. Finally, it disclosed that BP (at the time of the request) were corporate members and had paid £27,000 for the financial year 2008/09

What’s even funnier is that Tate itself has proudly revealed this kind of information: the amount that Unilever sponsored the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall commissions has been publicly available throughout the 12-year relationship. The agreement shows the incremental price increase through the sponsorship period:

– £1.25m 2000 – 2004 (£250,000 annual sum) through to £2.16m for 2008 – 2012 (£432,000 annual sum)

And Tate has also publicised several funders for Tate Modern’s new extension – a £214m project: £50m from the last government, £7m from GLA, £5m from Wolfson Foundation and £10m from shipping magnate Eyal Ofer.

These are not ‘Hidden Figures’, shrouded in secrecy – these are public bodies being seen to be transparent and accountable about their dealings with the coporate sector. What conceivable reason could there be why Tate can’t do the same with BP?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu is one of many calling for an ‘apartheid style’ boycott of those fossil fuel companies who are responsible for blocking progress on climate change:

People of conscience need to break their ties with corporations financing the injustice of climate change. We can, for instance, boycott events, sports teams and media programming sponsored by fossil-fuel energy companies. We can demand that the advertisements of energy companies carry health warnings. We can encourage more of our universities and municipalities and cultural institutions to cut their ties to the fossil-fuel industry.

The amazing efforts and achievements of the divestment movement means that universities and faith groups are at the cutting edge of the paradigm shift that is needed in the fight against climate change: it’s high time that supposedly progressive institutions in the cultural sector starting showing some real leadership too.