Shell declares it may go back into Cambo and the oilfield’s exploration license is extended by two years. The British government pushes for renewed drilling in the UK North Sea. There is public outcry at the Chancellor’s failure to defend households from the attack on living standards driven by price inflation. The Russian government announces that ‘unfriendly states’ will need to pay for gas imports in roubles. The global oil price rises again to $120 per barrel. Could these distinct events be indications of a tectonic shift in the politics of oil and gas?

It is well understood that the energy systems of the Industrial World have undergone repeated shocks and transformations in the last century, could we be in the midst of another? Can we use this as the springboard to leap beyond fossil fuels?

On March 19th as war raged around Kyiv and Mariupol, at a community centre in Torry, part of Aberdeen, Platform and Friends of the Earth Scotland were showing the new documentary, Offshore. As one viewer tweeted: ‘Climate Change is a disaster … that requires a clear response to achieve a Just Transition. This film can be an inspiration for the way!’ A fine response for the beginning of the film’s tour to communities across the UK. It may seem that Ukraine is a world away from this film and North East Scotland, but the Just Transition out of oil and gas production in the UK will only take place in the context of global politics of energy and will inevitably be impacted by shocks within it.

Maybe we can learn from the oil crises of the past. Both 1973 and 1979 are held up as years in which shocks altered the geopolitics of energy.

During the 1973 ‘Oil Crisis’, sparked by the Arab-Israeli War, the price of crude jumped from $22 to $61 per barrel[1], cars queued in the Petrol Panic, and the cost of energy fatally wounded the Social Democracy of Post-War Britain. This economic disruption assisted those aiming to attack the political settlement built on the Welfare State and nationalised industries that drove rising equality in the UK. Oil exploration in the North Sea became a security priority as the British government feared being ‘held to ransom’ by the oil producing states of OPEC. And on the back of oil prices remaining high, drilling offshore in the UK sector became profitable for British and US oil corporations, assisted by the highly beneficial tax arrangements made by the state.

In 1979, the Iranian Revolution and the subsequent Iran-Iraq War, once again led to a doubling in the cost of crude[2], but this time it generated a radical increase in British state income from the UK North Sea. The higher oil price provided the tax revenues that enabled the Thatcher government to ride out mass unemployment as it implemented radical economic polices – most dramatic of all being the battle against the trades unions and the closure of the coal mines. Within the energy industry, the new crisis enabled oil and gas traders come into their own. The establishment of the London International Financial Futures Exchange in 1982 symbolised this new phase, founded on the trade in financial instruments linked to oil rather than purely the trade in physical barrels of crude. Meanwhile the oil corporations also changed, embracing financialization and becoming bastions of the Neoliberal model that underpinned the Conservative and then the New Labour governments.

In Crude Britannia we explore these shifts, and the key characters in the oil business and politics that drove them, from Peter Walters CEO of BP, to Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, and back to John Browne another CEO of BP.

The war in Ukraine is now a month old, and it may well be far too soon to draw predictions that later prove to be fatally wide of the mark. But it seems necessary to consider the wider implications and so this piece is written in the spirit of debate, with a desire to engage in discussion. It has arisen from exchange between several of us focused on energy matters and we are keen to hear your reflections.

The indicators that suggest tectonic shifts, on a scale that might echo 1973 and 1979, are multiple:

The brutality of the war, the unexpected strength of the Ukrainian resistance, and the slowness of the Russian advance, imply that these battles may be long and drawn out. It is possible that the process of peace talks will halt the fighting, but the conflict will remain intense for some time. As NATO is understandably reluctant to engage in direct military conflict, the importance of sanctions – of the Economic War – grows ever stronger.

The speed and scale of the corporate withdrawal from Russia, led by BP putting its 19.7% stake in Rosneft up for sale, shocked many financial analysts and media commentators. Such action is extremely rare in the history of the oil industry. After the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the US and EU sanctioned Rosneft, but BP held on. So why now? It is possible the companies are playing for time, that they are hoping that peace will come speedily and they will soon be able to return to the assets that they declared they would sell.

But if the war is prolonged, and the brutality of it makes Western governments and civil society shun Russia over the longer term, then any return to those ‘lost’ oil and gas fields will be far harder to achieve. In the meantime, Russia has banned foreign investors selling their assets, although finding buyers at present will be hard. It is possible that Russia will expropriate these assets, including BP’s 19.7% stake in Rosneft.[3] A former BP executive told the Financial Times in mid March that the withdrawal marks ‘the end of an era, “a complete geopolitical reset”, that could cut off much of the world from Russian resources, business and culture for a generation’.[4]

On 24th March, Larry Fink CEO of BlackRock, one of the world’s largest private finance institutions with $10tn under management, issued his annual letter to shareholders[5]. Fink solemnly declared: ‘The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalization we have experienced over the last three decades. We had already seen connectivity between nations, companies and even people strained by two years of the pandemic.’ He spelt out the role of corporate finance in this struggle: ‘The invasion has catalyzed nations and governments to come together to sever financial and business ties with Russia. United in their steadfast commitment to support the Ukrainian people, they launched an “economic war” against Russia… Capital markets, financial institutions and companies have gone even further beyond government-imposed sanctions.’[6]

Fink’s words have immense power to influence the markets and indeed the corporations in which BlackRock holds substantial shareholdings. Significantly the institution holds 8.8% of the shares of BP[7], making it the oil company’s largest shareholder[8]. It is reasonable to assume that the board of BP discussed with asset managers at BlackRock before deciding to sell out of Rosneft. BlackRock also owns 7.3% of Shell.[9]

Perhaps Russia will become a ‘pariah economy’ to Western nations and be largely shut out of globalised trade with them, whilst maintaining its exchange with China, India and a range of other nations? Arising from this prospect there are already clear tensions between the US and China, and indeed UK and India. Whilst elsewhere the conflict is creating new rapprochements: between the UK and Iran, as indicated by the release of British citizen, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe[10], and between The States and Venezuela, with the release of US citizen, Gustavo Cárdenas.[11]

At the key resolution in the UN on March 2nd when 141 nations voted against Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, it was notable that China, India, Iran and Venezuela abstained or had no vote recorded. Also among that group was Algeria, Angola, Botswana, Burundi, Central African Republic, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Togo, Uganda, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. The sheer range of African states is striking and illustrates that the nations of this continent are not necessarily allied to the western powers. The Russian state, aided by mercenaries such as the Wagner Group, directly supports a number of governments such as in Sudan and Mali[12]. It may well be that oil and gas extraction by key exporters such as Nigeria, Mozambique, Algeria and Angola becomes a greater source of conflict.[13]

A debate rages within the EU as to whether there should be an embargo on Russian oil and gas, as has been repeatedly requested by the Ukrainian government and is being enacted (albeit partially and slowly) by the US, Canada and UK. (See our earlier blog on actions by dockworkers on Merseyside and the Thames.) An embargo on Russian gas would have a profound impact on the economy of Germany and other states, possibly triggering a recession across the EU. However Germany, which is dependent upon Russia for 52% of its gas and 34% of its oil, has announced its intent to cease all gas and oil imports from Russia by mid 2024.[14] Poland has declared a similar intention. These are remarkable geopolitical decisions even if implementing them proves extremely challenging. It is possible that the decisive act on gas exports may be taken by the Russian government. The declaration that gas purchases must be paid for in Roubles from April (and the battle over this that is currently underway) and the dramatic rise in Liquid Natural Gas exports from Russia to China, maybe the first signs of Russian action. However to loose that the European export market would pose huge challenges for Russian gas industry and the state.

As the Financial Times reported, Konstantin Simonov, head of the National Energy Security Center in Moscow, says he expects Russia to speed up the construction of gas pipelines to China, boost oil sales to Beijing and lean on existing Chinese co-operation in oilfield services. “It is clear that China will try to take advantage of this situation here, too. There are no illusions,” he says.[15] However Simonov may not be the most trustworthy commentator on these matters, and for Russia to export gas from the West of Urals fields to China may not make economic sense.

It is possible that Russia is moving into a closer relationship with China (although China is being reticent), but it is certain that there is a parallel process among western states. After the chilling of relations between the EU and the US during the Trump Administration, there is now a far warmer relationship between the two blocs, as both parties cleave to NATO and explore ‘energy security’ measures together. Germany may have announced its desire to come off Russian gas, but in the same breath there are moves to strengthen dependence on the importation of LNG from states such as the USA. In the US there has been a long struggle against LNG and the gas fracking that underpins it, and these geopolitical shifts will undoubtedly make that battle harder to win.

Should an official embargo on Russian oil and gas be imposed, or the Western corporations cease to buy it (witness Shell’s intense embarrassment over Russian oil purchases), the hydrocarbons of the world’s largest gas exporter and second largest oil exporter, may be shut off from parts of the global market. (Significantly it may not be blocked from China, India and the many African states noted above.) This will strengthen the hand of other oil producers such as Saudi Arabia, Canada and the US[16], and may lead to an easing of embargos on Venezuela and Iran. By all accounts it is likely to ensure oil and gas prices remain high for the duration of the war in Ukraine, and if Russia is kept as a ‘pariah economy’ by western states, then for far longer. A month before the invasion of Ukraine the global oil price stood at $80 a barrel, since that point it has hit around $120 a barrel twice.[17] These rises in fuel cost need to be understood as combining with soaring food prices, especially in wheat and sunflower oil. This could have huge impacts across the Middle East and Africa.

If these events are the signs of a tectonic shift, then how might that play out in the UK?

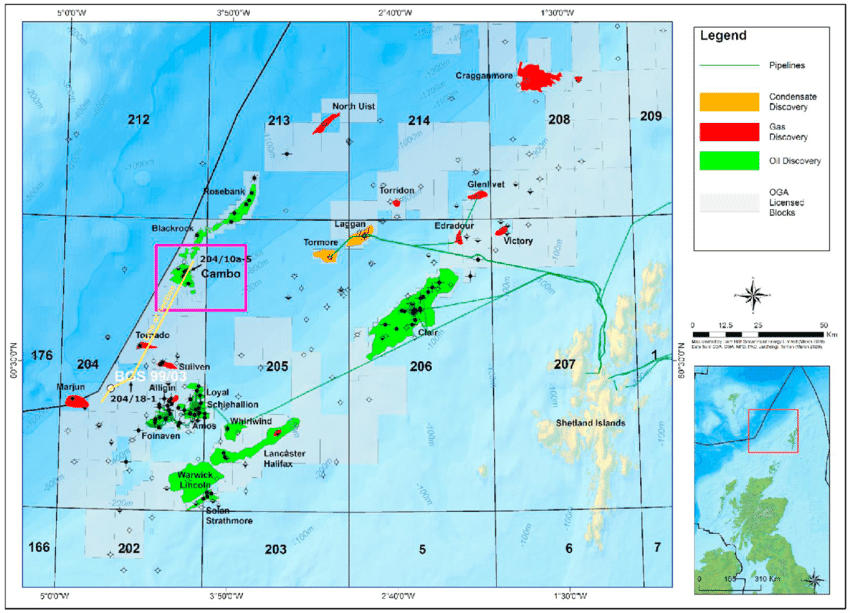

In the immediate term the war strengthens the hand of the oil and gas companies, and the financial institutions behind them, that have long argued for a continuation of exploration in the UK North Sea. The notion that the development of oil fields such as the controversial oilfield Cambo will get Britain out of being ‘held to ransom by Putin’ is laughable. The UK only imports 4% of its gas and 8% of it oil[18] from Russia, Cambo will take several years to produce oil and there is no requirement that its output should be sold to British refineries rather than onto the global market.

But in the short term the war and its impact on prices allows the UK and other western governments to call for renewed drilling. The weight of state support to the oil companies has meant, at the very least, that the exploration license for Cambo has been given a two-year extension by the Oil & Gas Authority (recently renamed the North Sea Transition Authority[19]). It is clear that the war has similarly revived the calls for the UK to lift the moratoriums on fracking, which may result in Cuadrilla stopping its planned capping of fracked gas wells in Lancashire[20].

On the opposing side, the rise in fuel prices, the cost of living crisis and the obvious link between fossil fuels and war strengthens the hand of those calling for the UK to make a bold leap out of gas and oil and into renewables. Prime Minister Johnson has felt obliged to call for a renewed drive towards wind power, both offshore and onshore, and to lift planning restrictions on new nuclear plants. The latter proposal, like that on offshore drilling, neglects to reveal just how long it will take to have nuclear energy systems on line and providing electricity, whilst there are continuing concerns around the degree to which schemes such as that at Hinkley Point and Sizewell C make the UK dependent on Chinese capital.[21]

But as the author Nick Robins has pointed out, the ‘Oil Shocks’ of 1973 and 1979 did not only thrust Britain ever deeper into oil and gas – with the massive ramping up of UK offshore production and the building of the national gas grid – they also empowered the birth of ‘Alternative Energy’.

Key works in the environmental movement were published in the early ‘70s : The Ecologist’s ‘Blueprint for Survival’ (1972), The Club of Rome’s ‘The Limits to Growth’ (1972) and EF Schumacher’s ‘Small is Beautiful’ (1973). Whilst the Centre for Alternative Technology in Machynlleth, Wales was established in 1972. All of these were the seeds of much of the world that we now live within. Fuelled by the same movement, Vestas launched its first commercial wind turbine in 1979. It has taken far, far too long for this technology to be truly embraced but forty years on, Denmark draws around 46% of its electricity from wind over the year, and the UK draws approximately 27%.[22]

It is inevitable that the oil and gas industry will utilise the crisis to drive us deeper into fossil fuel extraction, as the examples of Shell’s drive for Cambo and Cuadrilla’s push to reopen wells show, but might the crisis also be used by those who are pushing for a democratically controlled, publically owned renewable energy system? Whilst in the 1970s renewable energy systems were in their infancy, considered ‘alternative’ energy, now in the UK we have an array of mature technologies – including wind, solar, energy efficiency, heat pumps – and the widespread public acceptance of the pressure of climate chaos.

The Just Transition was never likely to be a smooth shift from oil and gas to wind and solar, might a future generation look back at the current crisis as being the jolt that pushed the UK to make a bold leap? The ‘leg’ of Net Zero has emphasised the low carbon emissions of renewable energy, but this current crisis illustrates a second ‘leg’ of fossil fuels being unstable in supply and volatile in price. Might we use both of these limbs as we jump forward?[23]

There are positive signs of this. Greenpeace UK has launched its Get off Gas campaign. An array of Opposition MPs, including Jon Trickett, John McDonnell, Mick Whitley[24] and campaigning groups such as We Own It, have called for the establishment of a public energy company. Whilst Caroline Lucas MP has called for a nationwide programme of home insulation[25], a central demand of campaigners at Fuel Poverty Action and the direct action group Insulate Britain. Whilst the government could tackle the rising costs of domestic fuel by ensuring the energy companies bear the burden of price rises, as has happened in France.[26]

In the realm of finance, Sean Kidney, head of the Climate Bonds Initiative[27], has highlighted the potential for ‘freedom bonds’ – similar to the Liberty Bonds issued by the US Government to finance its transformation of the American economy during World War II. Meanwhile the war has catalysed the movement to push pension funds to divest from fossil fuel stocks, not least by revealing just how many local authority pension schemes hold shares in Russian oil companies[28].

Larry Fink also declared that the search for alternatives to Russian oil and natural gas “will inevitably slow the world’s progress toward net zero [emissions] in the near term”. But in the “Longer-term, I believe that recent events will actually accelerate the shift toward greener sources of energy” because higher prices for fossil fuels.[29] The challenge will be how to redirect capital – especially ‘workers capital’ in the form of pension funds – towards projects that assist a Just Transition and phase out fossil fuels, rather that schemes focused purely on capital return.

There is no doubt that that shift from oil and gas production in the UK, coupled with the vast undertaking to implement Zero Carbon plans in cities across Britain, will require a massive leap by civil society, political bodies and financial institutions. For communities such as Torry, Aberdeen to shift from half a century of being entwined in the offshore industry and avoid the impacts that the threatened Energy Transition Zone (being valiantly fought by the Friends of Saint Fitticks Park), will require the whole of British society to undertake a jump into new energy economy. This brutal war, and the oil and gas shock that we are currently experiencing, might unwittingly provide the catalyst for that jump. Now is the time for a radical reduction in our dependency of fossil fuels.

*

This piece was built from busy exchange with Simon Pirani, Emma Hughes, Andy Rowell, Ben Lennon, Nick Robins, Rob Noyes and Kolya Abramsky. It draws from the work of Terry Macalister, Gaby Jeliazkov, Rosemary Harris and a forthcoming piece by Nick Robins. Many thanks to them all, and in the hope of much further discussion.

*

[1] https://www.macrotrends.net/1369/crude-oil-price-history-chart

[2] https://www.macrotrends.net/1369/crude-oil-price-history-chart

[3] https://www.ft.com/content/e9238fa2-65a2-4753-a845-ce8129f93a0c

[4] https://www.ft.com/content/e9238fa2-65a2-4753-a845-ce8129f93a0c

[5] https://www.ft.com/content/0c9e3b72-8d8d-4129-afb5-655571a01025

[6] https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-chairmans-letter

[7] https://fintel.io/so/us/bp/blackrock

[8] https://simplywall.st/stocks/gb/energy/lse-bp./bp-shares/news/bp-plc-lonbp-is-largely-controlled-by-institutional-sharehol

[9] https://fintel.io/so/gb/rdsb/blackrock

[10] https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/uk/iran-releases-british-iranian-woman-nazanin-zaghari-ratcliffe-1.4828408

[11] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-60675469

[12] https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2022/03/21/how-russia-is-pursuing-state-capture-in-africa-ukraine-wagner-group/

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/28/cold-war-echoes-african-leaders-resist-criticising-putins-war-ukraine

[14] https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-aims-to-be-nearly-free-of-russian-oil-and-coal-by-years-end/

[15] https://www.ft.com/content/e9238fa2-65a2-4753-a845-ce8129f93a0c

[16] https://www.ft.com/content/df47949a-380a-43ca-9286-dfa89ed9016e

[17] https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/crude-oil

[18] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-to-phase-out-russian-oil-imports#:~:text=Russian%20imports%20account%20for%208,%2C%20Saudi%20Arabia%2C%20and%20USA.

[19] https://www.nstauthority.co.uk/

[20] https://news.sky.com/story/climate-change-cuadrilla-ordered-to-plug-and-abandon-shale-gas-fracking-wells-in-lancashire-12538040

[21] https://www.ft.com/content/95524dfc-6503-48c7-85ad-a116bdf2c9ed

[22] https://inews.co.uk/news/storm-eunice-turbines-generate-almost-50-per-cent-of-uk-electricity-needs-during-gale-force-winds-1470963

[23] See also the work of Nigel Topping – High Level Champion for Climate Action at COP26 – https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/power-freedom-net-zero-nigel-topping-1e/

[24] https://www.birkenhead.news/birkenhead-mp-calls-for-energy-sector-to-be-brought-back-into-public-hands/

[25] https://www.greenparty.org.uk/news/2022/02/03/caroline-lucas-mp-response-to-ofgem-announcement-on-energy-price-cap/

[26] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/jan/14/france-edf-cap-household-energy-bills

[27] https://www.climatebonds.net/about/speakers-bureau/sean-kidney

[28] https://bylinetimes.com/2022/03/25/profiting-from-putins-russia-quarter-of-council-pension-funds-invested-in-russian-firms/

[29] https://www.ft.com/content/0c9e3b72-8d8d-4129-afb5-655571a01025