How We Won, How We Build On It

Authors: Rosemary Harris (OCI), Rosie Hampton (Friends of the Earth Scotland), Gabrielle Jeliazkov and Connor Watt

The UK government’s “North Sea Future Plan” was released on 26 November 2025, setting out the overarching objective of fostering an internationally-leading offshore clean energy industry in tandem with a sustainable transition away from new oil and gas. Supporting objectives include:

- To ensure oil and gas workers and the supply chain can take advantage of the opportunities from the clean energy transition, creating a global blueprint for a transition which supports prosperity, jobs, economic growth, communities and energy security; and

- To take a globally standard setting, 1.5°C and climate science aligned approach to future oil and gas production.

On the second supporting objective, after years of government inaction and industry influence, the Plan commits the UK to a near-total ban on new oil and gas licensing in the North Sea, an achievement driven by relentless campaigning, legal challenges, and grassroots activism. While the move marks a significant policy shift and includes a formal end to the long-standing “Maximising Economic Recovery” policy, it stops short of phasing out existing oil fields or rejecting unproven technologies like carbon capture and hydrogen, which risk prolonging fossil fuel dependency.

On the first supporting objective, the Plan outlines a new North Sea Jobs Service and North Sea Future Board, but makes no new funding commitments towards transition support for workers or on job creation, job quality and investment. Workers remain underserved by transition measures that do little to tackle the structural barriers they face in moving to renewables. This milestone is a hard-won victory, but a just transition in line with 1.5°C demands much more.

Introduction

From passing the Climate Change Act in 2008, to declaring a climate emergency in 2019, and being a key player in the move against using export finance to fund fossil fuel projects abroad, the UK has long fancied itself a climate leader. However when it’s come to real action on the UK’s own oil and gas production, the successive governments have stuck rigidly to their policy of Maximum Economic Recovery, with then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak in 2023 defending plans to drain ‘every last drop’ of oil and gas out of the North Sea.

For the world to be on track to phase out fossil fuels by 2050, rich global north countries like the UK must commit to and plan for an orderly phaseout of oil and gas production on a much faster timeline. The UK’s fossil fuel pollution and extraction has contributed disproportionately to the climate crisis, while also helping the country amass immense wealth.

Last month, however, years of tireless campaigning paid off. The UK government formally committed to ending new oil and gas exploration, becoming the largest producing nation to take this step. While this move alone won’t deliver climate justice, it’s a major milestone and a foundation to build on.

So how did the UK go from defending maximum extraction to banning nearly all new licensing in just two years? While the licensing ban grabbed headlines, Labour’s plan goes deeper, offering a broader vision for the future of energy in the North Sea. How did we get here, how far have we really come, and what must happen next?

How we got here

In 2019, the Scottish, Welsh, and UK governments each declared a climate emergency within days of each other. However, they largely ignored how deeply the UK remained tied to domestic fossil-fuel extraction and how that commitment undermined real climate action. In response, Oil Change International, Platform, and Friends of the Earth Scotland released the Sea Change report in May 2019. The report exposed the major climate impacts of UK North Sea oil and gas extraction and argued for an urgent shift away from fossil fuels, one that creates good jobs in alternative industries and ensures oil and gas communities benefit from the transition.

The rest of 2019 saw grassroots climate action explode – from school strikes to Parliament lock-ins and the rise of groups like Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion. In 2020, UK campaigners secured a major win when the government became the first in the Global North to end overseas fossil-fuel finance, increasing scrutiny of its weak domestic action.

The COVID-19 shutdown created new space for just transition work. When a third of oil and gas workers were either furloughed or laid off nearly overnight,Platform, FoES, and Greenpeace UK published Offshore, based on a survey of 1500+ oil and gas workers. In 2023, FoES and Platform published Our Power, diving deeper into workers’ experiences and their vision for a fair shift to renewables.

Meanwhile, other reports showed how strongly governments and industry remained tied to fossil fuels. Global Witness found that UK officials met oil and gas lobbyists an average of 1.4 times per working day in 2023, and OCI’s Troubled Waters showed that all North Sea countries, with the UK in second place, are failing to meet their Paris obligations.

With the government stalling and siding with industry, the movement fought in the streets and in the courts. In the Paid to Pollute case, three claimants, backed by climate groups, took the government to court for subsidising major polluters. Thousands joined the Stop Cambo and Stop Rosebank campaigns, delaying both oil fields and pressuring developers like Shell to withdraw. The momentous Finch ruling reinforced these wins by requiring new oil and gas projects to count their full climate impact (including scope 3 emissions from burning fossil fuels), blocking many proposals.

All of the above led to the government’s Future of the North Sea consultation in spring 2025, where we consolidated years of hard work campaigning to one final push – including our response to the consultation. It has been years of dedicated graft that has brought us the ban we have today. So what exactly have Labour set out for a transition away from fossil fuels?

What has (and hasn’t) been banned

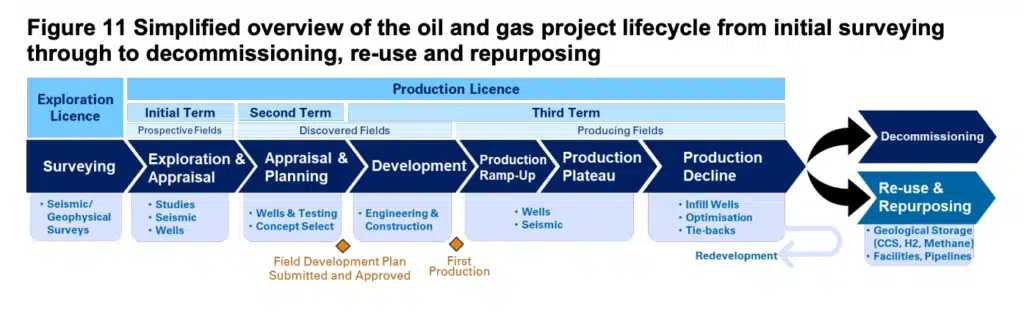

Overall, the licensing ban is a good start, and in some regards stronger than some feared, with minimal loopholes and largely maintaining the Labour government’s original manifesto promise. The ban will cover new licences for both the exploration and production licence phases in the diagram below.

However, it does not end companies bringing to production new fields within already existing licences, or put a timeline on the phase-out of existing fields. In fact, they have explicitly stated that their other commitment is to “enable existing fields to stay open for their lifetime”.

Staying within 1.5°C requires leaving most already-approved oil and gas reserves in the ground. Any new field, like the Rosebank project, breaks that limit. The UK, with its historic responsibility and economic capacity, should lead the world in phasing out existing fields quickly and fairly. Because the UK Continental Shelf is already a mature basin, the government could have taken a global lead by ending new North Sea development and shifting fully to proven, reliable alternatives.

Ahead of the announcement, many speculated that the government would use “tie-backs” to weaken the licensing ban. Tie-backs link new wells or fields to existing offshore infrastructure. Under the Plan’s new Transitional Energy Certificates, companies can apply for rights in areas next to existing licences, but only if there’s no need for exploration. For comparison, Denmark’s Neighbouring Block policy allows both exploration and production as exceptions.

Although the UK should be accelerating a managed phase-out instead of leaving room for tie-backs, Uplift’s analysis shows tiebacks offer only limited potential for viable new production and any that proceed would still need development consent.

End of MER

The future plans for the North Sea have also finally committed to ending the UK’s policy of Maximising Economic Recovery (MER) of oil and gas, securing a long fought win for climate campaigners. Since 2016, after a review of offshore oil and gas recovery from oil tycoon Sir Ian Wood, MER has legally bound oil and gas policy to extract as many economically viable barrels as possible. It has underpinned energy policy decisions made by the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and decisions made by the Treasury and HMRC about taxation, including the generous tax breaks offered to industry to develop new fields.

Under the new plan, the regulator will now have three objectives that it must balance:

- To maximise societal economic value of a relevant activity;

- To assist the SoS in meeting the net zero target and carbon budgets set under the Climate Change Act 2008; and

- To enhance the long-term benefits of the transition to clean energy technologies in the UKCS by considering workers, communities and supply chains.

Overreliance on unproven and risky CCS

Despite good news on the end of MER, a lot is left to be desired on plans for the future. Three key clean energy industries are identified for growth in the North Sea – offshore wind, CCUS and hydrogen. Leaving us with one proven and reliable industry, and two oil and gas industry pipe dreams (literally) that sell false promises of allowing polluting activities to continue.

The government’s Plan massively overestimates the potential for carbon storage in the North Sea, and does not address the significant issues with it, least of all the safety concerns, persistent cancellations, failures to stick to timelines and considerable underperformance in terms of capture rates. Carbon Capture has a 50-year record of failure globally despite enormous subsidies and remains extremely expensive compared to the alternatives. Meanwhile the government continues to overplay the ease with which gas infrastructure can be altered to use all forms of hydrogen and underplay the significant dangers and difficulties with transport and safety.

The status of almost every CCS project in the UK is either delayed, cancelled or undisclosed, and no carbon has been captured at a commercial scale in the UK, despite billions in subsidies. The level of public money flowing to CCS and hydrogen projects in the UK could and should be redirected to proven technologies like offshore and onshore renewables, public funding for worker transition and viable renewable energy supply chains to guarantee pathways for workers.

What’s in this for workers?

The consultation on the Future of the North Sea unfolded during major upheaval. The consultation opened a month before Grangemouth Refinery halted crude processing, and the government published its response, the North Sea Future Plan, a week after ExxonMobil announced plans to abandon the Mossmorran ethylene plant. As challenges like these become more frequent we need to see bold, visionary thinking and leadership.

The North Sea Future Plan is meant to ensure good, long-term jobs and investment in communities dependent on or impacted by the North Sea, with a specific sub-objective to ensure oil and gas workers can take advantage of opportunities arising from the energy transition. Yet within it, or in any of the other clean energy plans published by the government, there is an absence of a solid plan or industrial strategy to capture the public benefits of renewables, and this new Plan crucially makes no new funding commitments.

There are some limited wins. One being the creation of a “North Sea Future Board”, a Ministerial-led Board of experts to independently scrutinise how the transition is delivered on the ground. Crucially, the Board will include local and union representation. In addition, a working-level union group will be created to inform the Board on their tasks, the first being a focus on the supply chain. After years of workers and their unions demanding a greater role in shaping the transition, this is a cautious but welcome step recognising how those who built and power our energy industry should have a say in what comes next.

The plan also finally acknowledges the major barriers workers face when moving from oil and gas into renewables. For years, workers have highlighted the costly and duplicate training required for offshore wind, all at a personal cost. Although the government launched the Energy Skills Passport to fix this, it fell short. Workers expected a system that recognised skills across sectors and cut duplication and costs. Instead, it currently consists mainly of an online portal which allows workers to compare their skills and experience with active job listings.

The Plan’s direct transition support for oil and gas workers threatens to follow in the Energy Skills Passport’s underwhelming footsteps.The creation of a ‘North Sea Jobs Service’ establishes a national programme offering end-to-end career transition support for oil and gas workers leaving the industry to work in clean energy or other ‘growth sectors’. Support to change careers is a welcome step, but in isolation misdiagnoses the problem. While a required step, career support pales in comparison to the issues thrown up by an overwhelmingly privatised energy industry with high job insecurity and terms and conditions many workers report as worse than oil and gas.

More worryingly, such support schemes risk shifting the burden of successful transition on the shoulders of workers, suggesting struggles to find jobs in renewables are down to individual mistakes rather than a systemic problem. The current barriers to flourishing employment in the renewables sector are economic and political, and require a fundamental rethink of industrial strategy and the development of genuine routes into new careers.

While the government is making some good commitments around transition support, more is required than advisory boards and career-coaching services. The government needs to recognise the structural nature of the challenge and commit to shaping the renewables sector into a genuine engine of secure, well-paid employment.

What’s next?

While we have pointed out here the substantial difficulties and issues that need to be dealt with in the North Sea, it should be noted again what an achievement it is that, after years of tireless campaigning, the UK has enacted a ban on nearly all licensing in the North Sea. Any victory here belongs to the campaigners, activists, researchers and communities who never let up in the push for the UK to do more. And it’s this drive and commitment that we must now turn to what needs to happen next:

- A serious industrial strategy which centres workers and communities currently at the forefront of the transition: the booming renewables industry must be built for public good, not private gain, and crucially must create good quality, stable jobs which can provide a legitimate route out of the fossil fuel industries.

- A plan for an accelerated and orderly end-date for UK production before 2035, and an end to new development consents, starting with Rosebank.

- An end to the reliance on failed “solutions” like CCS and hydrogen, which have serious technical failures, expand the use of fossil fuels at taxpayers’ expense, and harm communities and the planet.