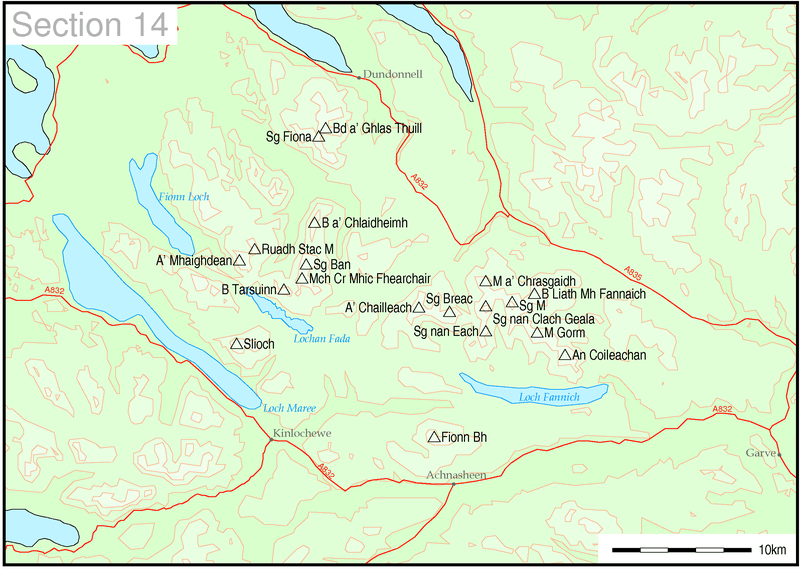

We’re descending from the peak of A’ Chailleach (The wise old Woman). Trudging down the steep slope of Sron na Goibhre (Under the Nose/promontary of the Goats) on the northern edge of the Fannich mountain range. My knees are exhausted as they absorb the shock of each step on this sodden mass of grasses and heather. With my brother Charlie and friend Greg Muttitt, we look 2000 feet below us and see Alt na Goibhre (The Stream of the Goats) plunging through a ravine and then meandering across the flatter ground to the southern shore of Loch a’ Bhraoin (Loch of the Rain Showers). In the bottom of the glen, I can make out the stone-walled circle of a sheepfold. Perhaps the cluster of stones beyond it are the ruins of crofts and the remains of ‘a township’, as a village in the Highlands of North West Scotland is called?

There are seven mountains in the Fannich range that rise to over three thousand feet. They lie in the midst of the vast tract of moorland, rock, bog and burn that is called the Fannich Forest. A forest almost entirely without trees. Perhaps ten miles from east to west, and five miles from north to south, it seems that the year-round human population of this forest is nil. There are a couple of hunting lodges and the estate is apparently owned by, is in the possession of, Dutch millionaire Albert Alexander Baron van Dedem. But it is truly possessed by hundreds of Red Deer, many Ptarmigan and Red Grouse, several pairs of Ravens and Buzzards and countless Meadow Pipits. For this is a ‘hunting forest’, a place for stalking deer and fishing for trout. A place of recreation. A place for blood sports and for walkers and climbers such as ourselves. I, like so many others who lumber up the mountains in pursuit of their peaks, can be blinded by the emptiness of this landscape to the fact that it was once busy with the grazing cattle and goats which belonged to the people who lived in the townships. This was common land once in the possession of the inhabitants of houses now completely erased.

This was not only a massive forced displacement of people, but also a rapid transition from one economic system to another. Through the ‘clearances’, the crofters’ lives and culture of collectively grazing black cattle on the mountain sides was violently replaced by the a new culture of the landowning class with extensive sheep farms with outlying sheepfolds, such as the one on the shores of Loch a’ Bhraoin. Sheep grazing to feed an industrial market in the south was combined with the culture of stalking and fishing. Herds of Red Deer and many Grouse were carefully nurtured on the hills, Trout and Salmon in the rivers were zealously protected in order for there to be good sport for those who rented the forest. In glens stripped of their population, the Mackenzie landlords (or lairds) financed the building of hunting lodges. The right to shoot deer with rifles and fish salmon with rods was purchased by the sons of the ruling class visiting from the south. In 1845 Hugh Mackenzie let out the Fannich Forest for the hunting season to the seventeen year old George Hay-Drummond, Viscount Dupplin, from Perthshire. Along with his friends, Viscount Dupplin returned regularly over the next fifteen years.

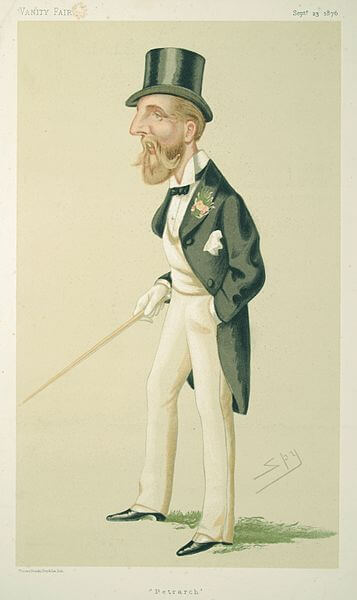

Meanwhile, famine stalked the land and the now landless peasantry. In 1846 there was potato blight in the North West Highlands. Thousands faced starvation, especially those that had been evicted and forced to live on poor soil by the coast. At the township of Scoraig on Little Loch Broom these resettled families were offered the chance to rent land that was black and stony. Unlike the picture of Viscount Dupplin above, I can find no images of the people of Scoraig at the time. But we can capture a rare moment of their Gaelic voices in the lines:

Sgoraig sgreagach, s’ dona beag I, Aite gun dion gun fhasgagh, gun phreas na coille!

Scraggy Scoraig, bad and little, No protection, shelter, bush or wood!

The starving were offered food by the local government in return for free labour on ‘public works’. From the mountainside as we descended from A’ Chailleach we could see cars on the A832, the road still known as The Fain, or ‘Destitution Road’. Built in the years after the famine across the estate of Hugh Mackenzie it provided a new route from Inverness to the west coast at Dundonnell. It also provided far easier access to the hunting lodges in the Loch a’ Bhraoin glen.

*

My head spins as I think of the cruelty and the injustice of these changes. Even now, 170 years later, the memory of them can fill the spirit of the place. In the bookshop in Ullapool on Loch Broom, there are many volumes that talk of this great wrong. Similar paperbacks are on the stands at WH Smiths’ in Inverness Station. This story is repeated in the panels of the Ullapool Museum and on many national TV programmes.

And yet, according to their own logic, the Mackenzie landlords saw their actions as ‘improving’ the land and the livelihood of its people. They saw the replacement of smallholder cattle culture with sheep culture, of townships with hunting lodges, as ‘development’ that would be of benefit to the Highlands and the nation as a whole. They saw the changes as inevitable and morally beneficial to the inhabitants. A Parliamentary Select Committee in 1841 made an enquiry ‘Into the condition of the Population of the Islands and Highlands’ and recommended that in the Loch Broom parish ‘the population must be got rid of’. Murdo Mackenzie travelled to London to testify to the Parliamentary Committee and asserted that his act of evicting people from the glens to the coasts was taken through ‘motives of humanity.’ Perhaps he also believed that the capital invested in the purchase of the estate six years previously would not generate sufficient return if these changes were not made? If so, he had the power to ensure that others, the evicted tenants, bore the burdens of that change rather than himself.

What can this history teach us? For much of the time that Greg and I have sweated up the mountains on these days, we’ve talked of ‘transition’. The questions, moral and practical, of how the shift from a fossil fuel culture to a non-fossil fuel culture can take place have rattled between us as we’ve put one climbing boot in front of the other. It seems clear to us, an absolutely inevitability, that in order to avoid the Earth’s climate rising above 2 degrees of warming as compared to the pre-Industrial era, we need to stop opening up new oil & gas fields and new coal mines across the world. This imperative is laid out in the report ‘Sky’s Limit’ that Greg wrote for Oil Change International in 2016.

But how is this seismic change in the foundations of the global industrial economy to take place in a way that is equitable, in a way that has the least impact on those directly effected by that change in terms of employment? We explore closely the relative effects of the ‘shutting down’ of an offshore oil field in the UK North Sea compared to the shutting down of an oil field in the Niger Delta. The UK does not export oil. Although sizeable, the industry around oil & gas production in Britain probably only underpins 1% of the country’s GDP. Because of a tax regime entirely rigged in favour of the oil corporations, the UK citizens are currently paying these companies to extract oil. The impact of shutting down North Sea production, and certainly not allowing the opening up of new oil & gas fields, would create a turbulence in the economy that could easily be handled by the UK as a whole. Indeed the turbulence would be infinitely smaller than that created by Brexit.

In contrast, oil exports underpin 70% of the government revenue of Nigeria[1]. Although the tax regime is once again rigged in favour of the powerful foreign multinationals who extract oil from the Niger Delta and offshore such as Shell and Chevron, there is a flow of dollars into the Nigerian Exchequer from these companies. If the Nigerian government were to declare that no new oil & gas fields were to be developed, it would come under immense pressure from foreign corporations, and in their wake, foreign governments. It would have an instantly negative impact on the value of the Naira and on the economy of Nigeria as a whole. However, for those communities in the Niger Delta who have been fighting for decades against the social and ecological destruction caused by oil extraction, the shutting down of the industry is a central demand. Without oil fields being shut down, there is little chance of social justice and environmental restoration taking place.

How then to balance between the shutting in of barrels of crude in the UK North Sea and the Niger Delta? And of course this conundrum is replicated across the globe, between states utterly dependent on their oil extraction industry – from Angola to Kuwait – and states whose economies are large enough and diverse enough to weather such a change – from Australia to Canada.

This question of imbalance is replicated between regions. The steady closing down of North Sea production is likely to have a far greater impact on Aberdeen and Lowestoft than it will on London and Manchester. How are the imbalances between regions within the same state to be equitably addressed in the process of transitioning to the post-fossil fuel economy?

*

The injustices that were perpetrated in the glen of Loch a’ Bhraoin and along The Fain, were made possible by a massive imbalance of power. The tenants had no rights, and little agency to resist the writ of the landlords backed by the British state in the form of the police and Parliamentary Committees. The injustices that happened in these glens, and across the Highlands, came about not just because of the shift from one economic structure to the next, but because of the power structures behind that shift. Because the landlords were able to act entirely as they wished and to make changes that were entirely in their interests, even if they may have convinced themselves and others that the changes would ‘improve’ the lot of their tenants. Whether or not such injustices are replicated in the transition to a non-fossil fuel economy, both within states and internationally, depends upon the distribution of power. For as it is said: ‘Power is the ability to ensure that others carry the burdens of change’.

The contemporary equivalent would surely be to leave the transition from oil & gas to a new economy in the hands of multinational corporations? If it is up to Shell to manage the ‘transition’ in Nigeria, or BP to manage the ‘transition’ in the UK North Sea, then is it not inevitable that the transition will be unjust? For they will act in the interests of their capital investment – just as Hugh Mackenzie did – if they are not constrained by a popular movement and government action to act in the interests of communities and ecologies.

To resist corporate power, and its abuse, in the transition away from oil & gas will require a great movement, a movement for a Just Transition.

However there are moments of this Just Transition, like bright stars at the fall of night, appearing in many quarters of the sky.

In 1997[2] the people of Eigg, one of the Inner Hebrides, brought their island under community ownership through The Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust. Like the townships around Loch a’ Bhraoin, Eigg had been a farming community since the Bronze Age, but in the nineteenth century the tenants were evicted by their landlord who turned the land over to sheep farming. The community buy-out in 1997 marked the return of power into the hands of the community. As if to symbolise that shift in power, nine years later the Trust established a renewable energy system, Eigg Energy, that is owned by the community and provides power to all the residents.

Their bold example inspired us in Platform to write in our essay ‘Energy Beyond Neoliberalism’:

‘The NHS was designed in 1948 by scaling up the Tredegar Medical Aid Society – a mutual health provision organisation in South Wales set up by miners and their families that had run for over fifty years. By scaling up this local community-controlled structure, the founders of the NHS fundamentally transformed the economy and politics of healthcare nationwide. Today, we need a comparable transformation of energy provision. Could Eigg – an island collectively owned by its inhabitants and entirely supplied by renewable electricity – be the Tredegar Medical Aid Society of energy?’

On 18th November 2017, on land that was once part of the township of Auchindrean, a new community-owned renewables energy scheme celebrated the ‘switch on’ of their small scale hydro-electric scheme called Broom Power. It will now generate electricity to local residents and revenue for the Ullapool Community Trust. The inhabitants of this loch and glen are gathering power back into their hands and using it to ensure that the shift from the fossil fuel economy to the renewable economy is taking place under community control, not under the control of the landlords.

This transition to an economy that does not destroy the Earth’s climate needs to be made, but at the same time it must above all be a Just Transition.

With thanks to Greg Muttitt and to David Iredale’s book: ‘Dundonnell of the Mackenzies’ (Phillimore, 2008). And with special thanks to Deirdre ni Mhathuna

[1] https://www.nationalplanning.gov.ng/index.php/news-media/news/news-summary/333-nigeria-s-oil-sector-contribution-to-gdp-lowest-in-opec-blueprint

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/sep/26/this-island-is-not-for-sale-how-eigg-fought-back