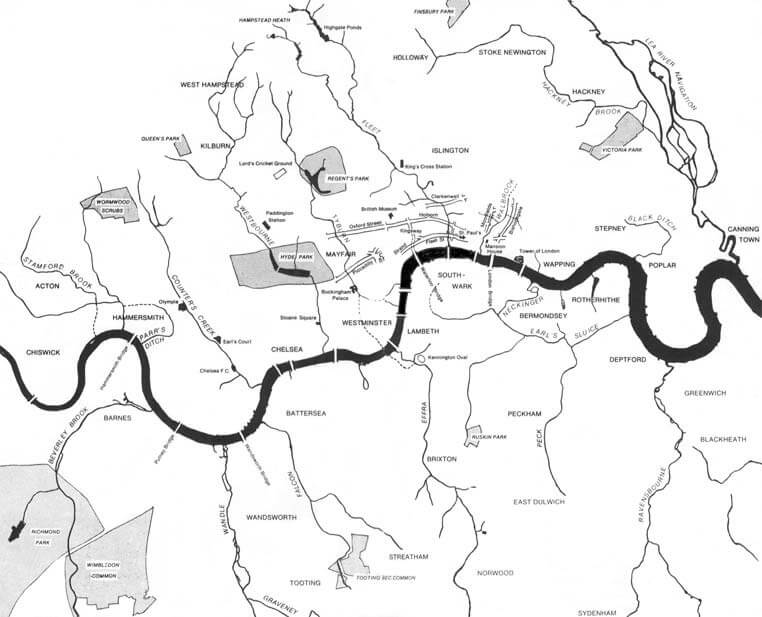

May 1st 1992 marked the first day of Platform’s project ‘Still Waters’: a month of street-based actions, walks, talks and art-interventions to unbury the Fleet, Walbrook, Effra and Wandle, three sewerised and one neglected river in central London.

‘Still Waters’ reframed London as a watershed. We aimed to reclaim London’s rivers from their hidden state, create desire, and begin action to resurrect them. Working on London’s rivers felt provocative in the context of the upsurge of a right-wing, free-market agenda in Britain in the 1990s, a time when bull markets and art markets were running fast and loose. The freshwater rivers, on the other hand, were pushing storm water, run-off, and human effluent. These were silenced voices, as were many of the losers in the privatising and asset-stripping times we were living in. The rivers had been mostly buried in another time of triumphant technofixes – the 19th century, a parallel that we drew out. Poison Me, Bury Me, Forget Me. *

Go here for a summary of what we did on each river.

The project took place along the river Fleet (Hampstead & Highgate to Blackfriars), Walbrook (Moorgate to Cannon Street), Effra (Norwood to Vauxhall), and Lower Wandle (Beddington to Wandsworth Town). The major practical impacts were that it led on to our art-ecology- energy projects “Merton Island” and “Delta” which produced locally sourced renewable power from the river Wandle. These in turn led to the founding of a new charity Renewable Energy in the Urban Environment (later joining with Carbon Descent).

Platform learnt alot from Still Waters. By researching the rivers and talking to dozens of people across London for that month, we gained a particular analysis of the ecological and democratic impacts of rapid growth of an industrial, imperial metropolis like London. And how London exported its models. Along the way, books like Ivan Illich’s “H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness”, or Gaston Bachelard’s “Water and Dreams” helped to position the project in terms of re-energising forgotten, disused or unheard democratic voices. This was in the context of a London whose elected assembly had been abolished in 1986 by Margaret Thatcher, along with six other metropolitan authorities. London’s well-being was in the hands of unelected quangos, consortia of business leaders like “London First” and embattled borough councils.

Still Waters was a recipient of the Arts Council’s new collaborative funds which, for the first time, supported work that brought artists together with people from other disciplines or expertise outside the arts. This project also marked a moment where Platform realised our activist work might be fundable (along with the questions that that raises.)

Context

Greater London runs with over 56 streams and rivers which flow into the Thames. By the 9th century, the Walbrook stream – around which the Romans built Londinium – was already silted up and buried. By the 1850s, most of the other central London rivers had become dangerously polluted through centuries of being used to get rid of human and industrial waste, as well as from run-off from the vast numbers of overflowing cesspits which leaked into the watercourses The poor, who could not afford bottled water and for whom the infrequent standpipes were inadequate, were victim to epidemics of cholera that reached levels even Westminster could not, in the end, ignore. In the hot summer of 1858, the stench of human and other effluent from the lowtide mudflats of the bigger rivers such as the Fleet and the Thames itself was so unbearable that Parliament itself couldn’t concentrate, hanging the curtains with lime-soaked curtains. Contemporary media dubbed this “The Great Stink”.

MPs were finally pushed into doing something, but unfortunately for our future ecology, they opted for endorsing the water-born solution to sewage, rather than the dry solution (earth closet) which would turn human waste into compost. Victorian engineer Joseph Bazalgette’s gigantic underground sewage system for London was implemented, standardising the WC (water closet). WCs had been a luxury, in use among the privileged since the late 18thcentury, but now would become the norm. Bazalgette’s system relied on the motive power of London’s rivers. His rationale was that they were already open sewers, so why not kill two birds with one stone. The use of fresh spring water to push human and other waste was now officially approved and rolled out across the empire as a triumph of Victorian engineering and hailed as a massive leap in sanitation standards. Visit the two original pumping stations at Abbey Mills, London E15 and Crossness, Erith

and you can see how Victorian’s embodied this ‘progress’ in architecture.

So, by the 1860s, central London’s great rivers were bricked over and made part of the sewage and drainage system for London with only three rivers surfacing above ground. These are the Tyburn which fills Regents Park’s lakes, the Westbourne which fills the Serpentine, and the Fleet on Hampstead Heath whose numerous springs fill the chain of famous ponds.

Today the system still uses drinkable water (which in London has been through seven sewage farms) to push our effluent. London’s freshwater streams and rivers are intercepted by transverse sewers, in the same basic model as Bazalgette’s, the flow of which takes sewage, drainage and run-off eastwards on both sides of the river to sewage plants. However, during flash-floods, the north-south valves are opened and the rivers flow along their courses, carrying their noxious load towards opened valves directly into the Thames.

The argument underpinning “Still Waters” was that to sewerise freshwater streams was a huge mistake. It was not a sustainable solution to urgent health issues among the poor, nor how to cater for the human need for fresh water and the ecology of mass waste. We also argued that it was yet another example of Victorian and imperial gigantism. This was a high-infrastructure engineering ‘solution’ that has set so many cultural precedents and has led to so much long-term damage. (Thames Water’s is currently building a ‘super-sewer’ in London, investing in water-born sewage for another few generations. Is this another massive, expensive techno-fix which misses the point?)

Thinking ecologically and about power and privilege, we asked “What kind of city buries its rivers?” and “What kind of city digs them up?”

Which city would you choose?

* From a poster made for Tree of Life, City of Life, flyposted along the Effra’s course, 1989