The newsfeeds hiss and rumble with stories of a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine.

We are all of us left waiting.

Is this truly going to happen, a military conflict between Russia and NATO? Or is this a fevered concoction that aids the Kremlin, the US Administration, and the UK’s flailing Prime Minister? Will the Russians undertake cyber warfare against the Ukrainian state? Or indeed against the UK, as is suggested?

Like a creature behind it all, the Leviathan of the gas supply system breaks surface.

Passing through the Ukraine are two massive pipelines, Bratstvo and Soyuz built during the Soviet Union, that transfer fuel from Russia to Europe. (We explored their history in The Oil Road.) Will war disrupt these gas arteries that pump exports from Siberia to the West? If supply is reduced to states such as Germany, then this has an impact on the amount of gas pumped from Europe to the UK, and the wholesale cost of it. Will Europe and the UK be hit by a massive gas price hike? Will the US, Qatar and other liquid natural gas suppliers be able to ship sufficient loads to European terminals to make up for a loss of supply?

Not only the gas system of the present, but that of the future becomes a weapon of war. The US pressures Germany to declare that the new Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, built to pump fuel directly from Russia to Germany, will be blocked from its final moment of commissioning in the event of a Russian attack on Ukraine.

And we are left waiting. Waiting within the machine of Crude Britannia.

As the diplomats discuss the fate of the conflict, the reliability of gas supplies becomes a key pawn in the game. Prime Minister Johnson suggests that dependence on Russian gas is blunting German resolve to stand up to the Kremlin, but by the same token the UK’s gas supply comes into focus.

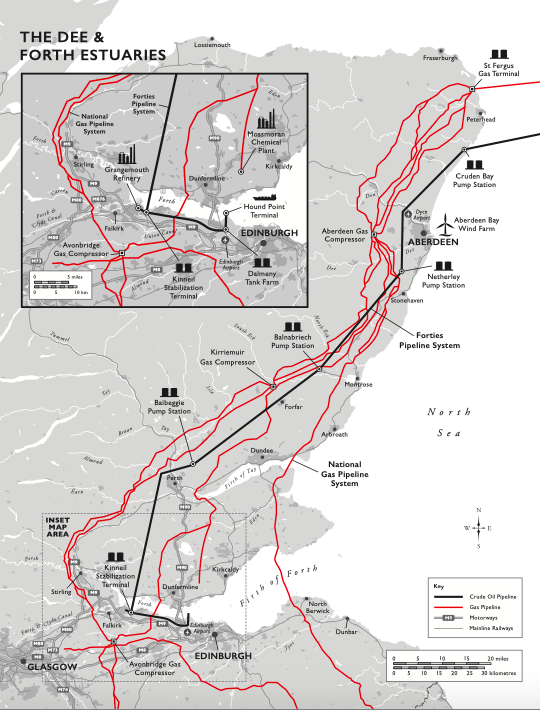

As you read these words, gas is being pumped from Foinaven field West of Shetland 120 miles across the seabed to the terminal at Sullom Voe, through the FUKA pipeline to St Fergus terminal north of Aberdeen, and from thence into the National Grid. (This is the route that those who promote the Cambo project, intend for its gas to follow.)

Gas is being pumped from the fields in Liverpool Bay to Point of Ayr into the grid of Merseyside, and from the gas fields of the Southern North Sea to terminals at Teesside and Bacton in Norfolk.

Gas is being pumped from the fields off Norway through the Langeled pipeline to Teeside.

Gas is being pumped from the Shah Deniz field in the Caspian Sea of Azerbaijan via the Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline through Georgia, Turkey, Greece, Albania, Italy and then the through Western European grid in France and Belgium to the Interconnector under the North Sea to Bacton.

Gas, frozen into liquefied form, is arriving by LNG ship at the terminals in Pembrokeshire and the Thames Estuary. The SCF La Perouse recently docked at the Isle of Grain terminal coming from Lake Charles in Louisiana, USA. The SCF Mitre is soon to arrive at Milford Haven from Peru.

All of these systems are in the hands of a few corporations. Foinaven under BP, Sullom Voe under EnQuest, FUKA and St Fergus under the Kuwait Sovereign Wealth Fund. The fields in Liverpool Bay are under ENI, much of the Southern North Sea gas is Shell’s. BP has the controlling stake in the Shah Deniz field and the Euro-Caspian Mega Pipeline. Qatar holds one of the two LNG terminals in Milford Haven. BP has the keys to the Isle of Grain’s LNG supply.

Into this vast machine of gas, owned by an array of private companies, we have placed much of our fuel security. Energy for the heating of homes and the fuelling of power stations that provide over half our electricity. This dependency enables the corporations that extract gas, and the companies that supply it, and the dealers that trade in it, to profit from the sale of gas. Our needs for heat and light are subservient to their private drive for profit. A clear example of this is how those companies export gas at a time when apparently Britain is starved of it.

The government’s statistics show that 31,975 Gwh of gas was exported out of the UK through the undersea pipelines between September and November last year. Exported by the corporations that extract it and supply it, going after higher prices in Continental Europe. As Richard Black – energy analyst and Director of the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit – says, this is not ‘our gas’ but ‘company gas’. This export was taking place last Autumn when the UK’s gas prices were sky rocketing, and driving many of the smaller household energy supply companies into bankruptcy. A process that has led the Treasury to just announce a ‘super tax’.

(There was no consideration from the oil & gas corporations to assist the UK state at this critical time. Just as they had refused to assist the British government back during the ‘Oil Crisis’ of 1973 – as we detail in Crude Britannia.)

So the conflict in Ukraine threatens to impact on supply which drives up the price of gas, which in turn drives up the cost of electricity and household fuel, which in turn drives up fuel poverty. A year ago 13% of households in England lived in fuel poverty. In some places, such as North Liverpool, the figure was double that. And the numbers will be much higher this Winter.

In Liverpool, as in most UK cities, sixty per cent of CO2 emissions come as a result of household and business fuel systems. The plan of that metropolis, just published, calls for the removal of gas-fired boilers from 270,000 homes. Britain’s attempt to address climate chaos will lie, in part, in the struggle to step free from domestic gas systems.

Our dependence on gas for warmth, hot water and cooking is remarkably recent. Only in the mid 1970s was much of the UK plumbed into the grid from the North Sea fields.

We have allowed ourselves to become embedded in these structures of Crude Britannia. To be dependent on this machine in which we are living, to be dependent upon this technical enterprise of climate destruction.

To step out of this machine we need not to maximise extraction of gas from UK territory – onshore or offshore – in some bid to be ‘independent’ from imported gas. Such a policy would not deliver the promised ‘energy security’ and would run directly counter to our need to reduce oil & gas production in order to have any chance of meeting our CO2 emissions goals.

Rather we need to radically cut energy demand, partly by reducing domestic gas use through insulation that will also tackle fuel poverty. And we need to increase the level of energy drawn from renewables such as wind – and do this under public ownership is a manner that builds democratic control, and removes the drive to profiteer that we see in the example of gas trading. Private energy companies have no incentive to eliminate fuel poverty. After all, as the electricity cables to Europe are laid in an echo of the gas pipelines across the North Sea, we may also be subject to renewables corporations profiteering on wind energy as much as the oil & gas companies profiteer on their commodities.

We wait for the news from the Ukraine and all the while we can hear the machine in which we are living. The hiss of the gas on the cooker’s ring. The rumble of the boiler.

Time to stop waiting, time to take further steps out of Crude Britannia.

With thanks to Terry Macalister, Darren Bennett and Rob Noyes.