The people of Notres Dame des Landes have won! The people of La ZAD have won! The airport that the French state have tried to build for 50 years has been defeated!

On 17th January President Macron decreed that the Nantes International airport, similar in size to Heathrow, would not go ahead after half a century of dogged resistance. It is a moment to celebrate in the long struggle against fossil fuel infrastructure and should inspire those fighting the expansion of Heathrow and Gatwick.

The French state, under President de Gaulle, first proposed that runways be built at Notre Dame de Landes, near Nantes in western France, in the early 1960s. Many farmers refused the compulsory orders and chose to defend this area of small fields, woodland, meadows and wetlands. In the 2007 they were joined by climate activists who squatted land that had been abandoned and established the community of La ZAD, buildings their homes on the site of the planned mega airport.

In the wake of this amazing victory comes a shadow. La ZAD, a ‘zone to defend’, is a self-governing commune of communes. The French state sees this as ‘land lost to the Republic’ and the decision to cancel the airport may well be followed by a decree that La ZAD must be ‘cleared’ and returned to ‘a state of law’, if necessary through the full use of the highly-militarized police.

It is around this question that the French media is swarming, with features filling the news from Paris Match to the right wing business paper Valeurs Actuelles. The articles are invariably negative, declaring the communards to be terrorists who are armed to the teeth. It is claimed that ‘clearing’ the 400 Zadistes will require two thirds of the mobile police of France, and that deaths may be inevitable.

Now, in this hour of victory, all those who have been inspired by La ZAD need to come together to support this amazing flower of rebellion. The community of resistance at La ZAD needs the support of the community of those around it to come to resist its destruction. Stay in touch with the struggle via the website and answer the call to the day action on 10th February.

At Platform we have a strong link to La ZAD, for John Jordan and Isa Frémeaux have been living there since April 2016. John and Isa, who work as the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, are long-term friends and allies. John was central to Platform from 1987 to 1997 and has since been involved in a number of projects, including co-creating And While London Burns.

*

Last Summer I was fortunate enough to visit La ZAD, and in memory of that I write the following.

We have arrived on bikes. We stand facing an enormous wooden barn. Beautifully constructed. Down each side a row of posts rises maybe 30 foot into the air, meeting crossbeams that span the space and support the great roof covered in slates. At the point where the crossbeams join the posts the wooden beam-ends are carved into the heads of dragons and hares, dogs and other creatures. At the apex of the roof are two crossed axes made of slate.

John explains that the barn had been constructed by a team of people, skilled artisans who love to build in wood, working with hand tools and without nails. They meet each year and raise a new building. In the summer of 2016, gathering from across France, they came to this ‘illegal zone’ to undertake their work. The communards of La ZAD were central to the labour. When the barn was complete, the two slate axes were attached to the roof, along with a bouquet of flowers, and a huge ‘Fest Noz’ (a traditional Breton dance party) was held on the earth floor of the building.

In front of the barn are gathered a number of figures. Women and men, mostly in their 20s and 30s, stripped to t-shirts, many with black forage caps. These Zadistes are working logs that have been dragged from the nearby woods, they strip the bark with hand tools prior to the trunks being fed into the sawmill and cut into planks. In the bright sunlight, standing at the edge of an extensive communal hayfield, the tanned faces of the communards exude a sense of purpose and a joyful energy. It reminds me of a photograph of the 1930s or perhaps earlier. The scene, the scale and the beauty of the barn, takes my breath away. I feel like William Guest, in Morris’s novel ‘News from Nowhere’, a traveller from the industrial world who awakes to find himself in some kind of utopia.

“Now I understand something”, I say to John, “This is not a TAZ, a ‘temporary autonomous zone’ like those proposed by Hakim Bey and realised in the No M11 struggle, before being recuperated by the state and capital. This is clearly something different. This is a PAZ, a ‘permanent autonomous zone’. The communards of La ZAD are building to remain here permanently. You can see it in the grand scale and the beauty of the barn.”

“Yes. Exactly!” replies John. He explains that the barn is to be used as a centre for forestry and carpentry on La ZAD. For the one and half thousand hectares of ‘the zone’ comprise of not only fields and meadows, farms and hedgerows, but extensive areas of woodland. Much of this is made up of mature trees, over 200 years old, of Oak, Maritime Pine, Sweet Chestnut, and Ash. The communards have become foresters, carefully tending the woods, felling some trees, dragging them out with horse or tractor, striping and planking the timber. Wood for construction. Wood for tables. Wood for fuel.

John explains that there are farms in the zone that have continued to operate since long before the early 1960s when the state declared the bocage – or traditional hedgerowed fields – of the village of Notre Dame des Landes to be the site of a new airport. Following the state’s announcement several farmers accepted the compensation offered and moved away, but many more refused to move and these still form the backbone of the resistance.

In 2009, inspired by Climate Camp at Kingsnorth Power Station in Kent, a Climate Camp took place on the site of the airport. The existing residents of the land invited the activists to stay, declaring “A territory must be inhabited to be defended.” As a result, many remained after the Camp and occupied the abandoned farmhouses, such as La Rolandière, the collective where John and Isa now live. These settlers brought a new life to the place, greatly increasing the numbers of people farming and foresting the land and starting up new initiatives. Now La ZAD has a fromagerie, a bakery, a brewery, a Free Shop shop, a forge, a bar and more. It becomes evermore a self-sustaining community, but importantly not a self-isolating community.

On another commune nearby, we come upon Camille working in a large open shed. Before living on La ZAD, Camille was a carpenter who had built her own boat. Here she is selecting and shifting recently sawn planks, working with another woman in her 20s. John explains that the latter is a contemporary dancer, but here, like everyone else, she pitches in, moving wood or undertaking whatever task needs to be done.

I watch the scene and have to remind myself that no one here works under contract, no one has an employer, no one has a line manager, and no one is paid. It makes me think of the words in the song ‘John Ball’ by Sydney Carter:

‘Labour and spin for fellowship I say

Labour and spin for the love of one another’

We cycle on and the road takes us into a patch of woodland. There is a young man stripping bark off recently felled trunks and cutting away the smaller branches. We stop to chat and admire his tools, a beautiful axe and curved scrapers, their blades so sharp that each has to be carried in its own leather pouch.

He takes us to the hut that the 100 Noms Collective built at the edge of the copse. Inside there is an array of implements – axes of all shapes and sizes, adzes and hammers. He explains that the ironwork was all made by the smith who labours in the communards forge. But the helves of the tools he crafted himself. He talks of the pleasure of working the wood to achieve the ideal shape. John asks him if he was a woodworker before he came to La ZAD. “No”, he replies, “I had never done anything like this before. I learnt all these skills at La ZAD.”

It seems that this site of an airport has become a permanent school of learning, of learning through doing. It seems that the community exists not only in its physical fabric, but also in in the minds of those who are living here. Consciously or unconsciously they daily undertake the task of constructing themselves as communards, as communists.

As we journey past one collective after the next we discuss what is happening here. Temporarily occupying land to resist a piece of industrial construction has been undertaken many times before, at Twyford Down, at Newbury, at the M11, at Heathrow, at Kingsnorth. But the shift to permanent occupation is fundamental. The people of La ZAD live with the daily threat that they could be evicted by a massive police raid that might come at anytime. But they choose to act in the belief that this largely self-supporting community, which exists outside the state, will remain forever.

It is this sense of a place outside the state that so enrages French politicians who declare that it is ‘territory lost to the Republic’, which must not be allowed to stand. John explains the intention of La ZAD is to ‘provide the material base for revolution’, that it is ‘outside the state’ but crucially not outside society. The people of La ZAD not only support themselves, but also support others struggling against the forces of capital. The communards have been actively build alliances with the Front Social, which is resisting Macron’s attempt to change French labour laws. They support other unionists and students in rebellion. And a project has been created that will provide strikers and their families, and migrants isolated in nearby Nantes, with food from the farms on La ZAD.

In the year leading up to the fifty-year anniversary of the Paris Événements, there is here an echo of the days of 1968. Although the uprising in the capital is most renown, the spark that lit the fire took place in Nantes. In this city just to the south of La ZAD, a strike began on 16th May 1968 at the Airbus factory. Crucial to the success of the worker’s action was the support that they received from radical farmers in the region underpinning the strike with the provision of food. That half a century later the region of Nantes should now be famed for a revolt that is inspired by the struggle against an airport, and all that Airbus stands for, is most fitting. It too is a spark that is inspiring revolt across France.

By the close of the morning we arrive back at La Rolandière. When the group squatted the abandoned buildings in April 2016, it was decided that La Rolandière would become a ‘welcome space’ for La ZAD. Or more precisely an ‘accueil’ which translates as something between a meeting point and a welcoming place.

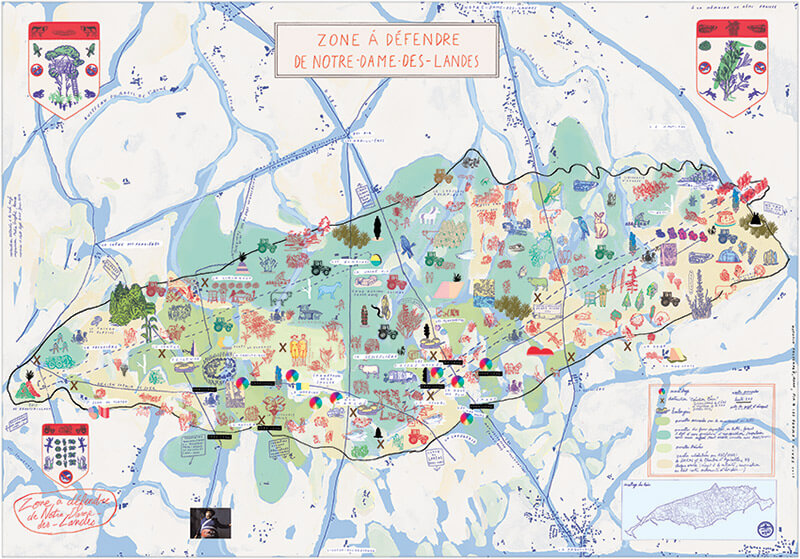

Half of the building was a cow barn long since unused. Painstakingly the concrete of the old stalls was stripped off the walls and the ground. A new wooden floor, made of old pallets, was laid down with exquisite care. On the wall was hung a large blackboard in a wooden frame, painted with a map of La ZAD, showing the woods, the collectives, the roads and the boundaries of the zone.

We walk into the room. The expanse of wooden floor is largely empty, ready to be filled with chairs and tables for a meeting. The wall, through which the cows had once entered the byre, is now mostly glass. Light fills the space. Above our heads a pair of Swallows swish in and out, making for their nest on the rafters. Their arrival is greeted by the eager chatter of chicks, yellow gapes wide above the rim of the mud and straw.

In the corner of the room, a stairway leads to the ceiling. There is clearly a trap door up there. A rope runs taut down to a yacht winch fixed to the side of the wooden stairs. We pull upon the sheet and the trap door opens. We climb the stairs and we are in a beautiful wooden space. This is Le Taslu, the library of La ZAD.

There are shelves and shelves of books perfectly organised, obviously maintained with care and love. There are books on feminism, books on the Paris Commune of 1871, books on ecology, anarchism, social movements, volumes of poetry, rows of novels, and so on. The room itself has been carefully shaped. The far end is curved like the interior of the bows of a boat. There is a nautical winch to raise the entrance hatch from below. This is a ship of books on the seas of rebellion. John explains that the constructing of the space had involved Camille, the boat builder turned Zadiste, who we had met earlier. “But in truth this is not the work of one designer, one artist, but it emerged from the collective and the minds and hands of the tens of people who built it. It is not an art work, a work, but an emergence, a collective emergence.”

As with the barn, I am struck by the beauty of this place. The patient care with which it has been constructed and maintained. There is such a sense of the love – which at its fundament requires care – that the communards have given, and give, to this land that they have occupied. That love can be a backbone of resistance and is expressed in beauty. But this is not beauty that enhances the capital value of the objects, for this library, this accueil, does not ‘belong’ to anyone, it is not private property but collective property. It cannot be brought or sold.

As with the barn, care in an act of resistance. The state may destroy this building in the next months, but in defiance of that threat the Zadistes have chosen to make it a place of beauty. In this, this ‘permanent autonomous zone’ once again stands in contrast to the ‘temporary autonomous zones’ of No M11 or the Newbury bypass protests that seemed to revel in a chaotic or hurried beauty. Here there is something different, in the barn and the accueil, there is a kind of calm and measured beauty.

It is not surprising that the space is used by writers and artists to hold events at La Zad. In February 2018, Eric Vuillard, set to win the Prix Goncourt 2018 (the French equivalent of the Booker Prize), will be speaking at the accueil. He follows in the footsteps of the likes of Isabelle Stengers, Starhawk and Kristin Ross. The latter is the author of an utterly inspiring book on the Paris Commune, fittingly entitled ‘Communal Luxury’.

We step through a glass doorway on the right side of the room and out onto a solid white-painted steel walkway. We turn left and are walking along the side of the house’s outer wall, 12 foot above the ground. Turn left again and this ship’s gangway runs along the end wall of the building. At the end of the walkway we find ourselves at what was once an electricity pylon, dragged here by tractor from several kilometres away and re-erected. We climb 10 foot up a ladder onto a landing, then up another ladder and onto another landing. Then up again. Then again. Finally we push open a trap door and we are on the top platform of the lighthouse. Le Phare! How fitting that, like the famed city of Alexandria, a lighthouse should stand above the great library!

It is an amazing edifice. Built by a team of people it rises up 50 feet. I hug the walls, despite the structure being very solid, and look out. The view is extraordinary, over fields and hedgerows, woods and the road stretching away north and south. The logic of choosing La Rolandière as the accueil for La ZAD becomes clear. This is indeed the meeting place near one of the entrances to the zone. It is here that visitors often come to first having travelled the few kilometres north from the city of Nantes.

This is a lighthouse in the middle of fields far from the sea, painted with its nautical stripe and fully equipped with searchlight and siren. Both will be used in any attempted eviction, used to sound the alarm to the collectives scattered over the zone. It is a beacon against the threats of the state. Like the barn and the bibliothèque, it is a monument, not uncontested, to the community of La ZAD. An expression of shared beliefs.

We look out over this place. It has surely been farmed since the Neolithic. Many of the trackways, the green lanes, between the fields are extremely ancient. And now the state, and private capital corporations, wants to clear the trees and bury the land under concrete runways changing it irrevocably. Emmanuel Macron has, a month before been elected President and his agenda is apparently both for ‘green’ and for ‘growth’ Which of these will win out? Will the airport be cancelled? Will La ZAD, such a profound symbol of ‘anti-growth’, be allowed to exist or will it be evicted by force?

Places of resistance have before been destroyed through the use of massive police numbers, places such as the No M11 protest in England or at the Sivens Dam in France. But there is something different about La ZAD. It is not a ‘protest’, it is a functioning ‘community’. It feels as though this is a determined attempt not to live in anticipation of revolution, but to be revolution. To live in revolution, now.

If I look at this place through the lens of ‘actually existing communism’, then I can better understand what I survey. Here is a place where there is no privately owned land, and where ‘the means of agricultural production’ are held in common. But it is also a place where people still own their own – books, beds, clothes, iphones, laptops, etc. It represents a mixture of the abolition of private property and the non-abolition of private property. And this mix is borne out in the architecture of La Rolandière, in which around eight people share the communal spaces – the field around the house, the dinning room, the kitchen, the bathroom and the office. Whilst at the same time they have their own private spaces – the caravans and cabins that they sleep in dotted about the field.

Before we descend the Le Phare, we look back down the road. There are two African men cycling past La Rolandière. Later a young guy from Mali comes to the house, and takes his place in the dining room to catch the rays of the wifi. John explains that two of the collectives see it as their role explicitly to provide refuge for migrants and those that have arrived in France without papers. Under the lighthouse, this community ‘outside the Republic’, provides a haven for those that the French state criminalises and declares illegal. And yet at the same time, La ZAD itself is criminalised by the state and declared illegal.

*

With many thanks to John Jordan, Isa Frémeaux and Jane Trowell

For further reading – ‘The Zad and No Tav’ – Verso – 2018