In August 2012 a dissertation for an MSc in Sustainable Development was submitted at Exeter University that was titled TATE-Á-TATE: An exploration of Soundwalks and their potential for achieving sustainability (download here). Written by Robert Black, it featured a three part auto-ethnographic response to participation in the Tate à Tate audio tour, a three part sound installation that was created in response to BP sponsorship of Tate and taking place in Tate Britain, Tate Modern and the boat journey in between the two institutions.

This is the first on a three part serialization of this auto-ethnography, detailing Robert’s response to the Panaudicon part of the audiotour that takes place in Tate Britain. You can download or listen to the Panaudicon in the soundcloud embed below, or download the whole three parts of the tour from the Tate à Tate website.

On Friday 7th of December 2012, there will be an en masse participation of the Tate à Tate audio tour featuring questions and answers with the sound artists. The listening starts at 2.45 at Tate Britain. More information here.

Spoiler alert – This account gives away some details about the tour if you don’t want to know anything about it before participating.

It is the morning of Friday 22nd June and I’m sitting at my breakfast table, part of my normal morning routine, except today instead of checking the news on my laptop I am on Platform’s new Tate-à-Tate website and I’ve just clicked the download button on their alternative audio tours. The tours are participatory interventionist sound artworks (Platform(a), 2012) commissioned by Platform, Liberate Tate and Art Not Oil to expose the reality behind BP’s sponsorship of our cultural institutions, but particularly the Tate galleries. I know a bit about Platform, their approach of combining art and activism with education and I know that what I am about to do is going to transform me into an activist, if only for the few hours I am listening to the tours, however I have purposely avoided finding out about this particular sound artwork in order to have an authentic experience. While I sit finishing my breakfast the unknown of what I am about to experience is exciting me and surprisingly making me slightly nervous. Taking a sip of coffee the familiar ping of ‘synching complete’ stirs me from my thoughts, the audio tours are on my phone and my activist toolkit (figure 1) is ready! I’m struck by how easy it all is. All I need are my headphones and phone, which are always on me anyway, shouldn’t I be in camo gear with a balaclava and some wire cutters? Pervasive media is changing the world and it seems Platform have cottoned onto this.

9:45am and I am standing outside the Tate Britain building, this is where Liberate Tate enacted their Licence to Spill (figure 2) performance during the Tate Summer party, knowing Liberate Tate’s involvement in commissioning the alternative audio tours spurs an affinity from myself to the three organisations that created the sound artworks; though they do not know me personally or that I am about to participate in their work there is, nevertheless, a sense of kinship and camaraderie.

As I stand in the entrance hall waiting for the gallery to open its doors and welcome me in I look around at the group of people waiting with me. Some have headphones. Are they about to take part in this subversive act with me? For the moment it is impossible to tell. This is one of the magical aspects of the audio tours, no one knows what you are doing, and there is nothing that can be done to stop me. In fact, I am about to be encouraged into the gallery, as a protester and cultural activist. It is a hugely empowering and free feeling, and yet, as I wait, nerves begin to build. The nerves of the unknown, of what is to come and what I might be asked to or be compelled to do. Rather than a feeling of fear that I imagine can occur in some more sensationalist forms of protest the overriding emotion here is one of naughtiness, knowing I am about to break the social conventions of what Tate and especially BP would like me to do in this gallery space. From an onlooker’s perspective, however, I will be behaving to the norm; after all, audio guides are a ubiquitous tool of the gallery. A reviewer of the tour echoes my feelings she says “there is something irresistibly subversive about slinking around an establishment with your headphones in, taking orders from a voice that resembles a TomTom or sleep aid recording” (Kelsall, 2012).

I put my headphones on and press play; I am transported from the empty ‘real’ Tate to a crowded, noisy Tate. Over this noise two voices emerge. The first an official computerised female voice attempting to synch my body and mind with her, a programme that will transform the building into a focusing device. I will be able to see through the walls, beyond the walls, crucially, she will allow me to see what is hidden. The second is a man’s voice or is he my voice?

“Hello, I’m Jiminy Cricket, I’m the voice of your conscience. Do you want to be a puppet, controlled by distant masters or do you want to be free? Then wake up!” (Biswas, 2012).

I find myself copying this voice, he (my conscience) tells me to raise my hand and I do. But he isn’t telling me, he is thinking and I am listening and doing. It is not a didactic voice. I am listening in to his thoughts. It is my choice whether to listen and agree, there is no pressure on me to follow and yet I feel compelled to, so much so that moments later I find myself sitting in a toilet cubicle and imagining myself in a swamp. Hey, this is fun. It seems the ‘ethical matrix’ (Heim, 2005) is already forming.

Ansuman Biswas’ sound artwork is called ‘Panaudicon’, this space, post-swamp, became the Millbank penitentiary, the first prison to be built in Bentham’s Panopticon design the perfect control structure where everyone could be watched by a guard who himself could not be seen. My ‘Panaudicon’ is the opposite of this it enables me to see “what’s behind the paintings and what’s behind the sculptures and so on, the beautiful things that Tate has put there. What’s the ugly truth, or what’s behind the beauty that is immediately on show” (Resonance, 2012). Biswas is subverting the space by reversing its traditional purpose, I was the prisoner only seeing what I was allowed but the guide turns me into the guard able to see everything at once.

My ‘guide’ is the computerised female, she directs me through the gallery space, through my alternate reality. I feel different from the other gallery visitors, they are part of the status quo, they’re using the gallery as it is meant to be used but I feel they are missing so much. They don’t understand the space; they are not experiencing it as I am. I move through the gallery but it is not just a gallery to me anymore, I don’t just see what is on the walls, I am beginning to see through the walls to an enlightened reality.

Now I am directed to the Clore gallery, but wait. My way is blocked. There are redevelopment works. The guide continues oblivious to my predicament and my immersion in the performance is lost as my mind detaches from my reality in the headphones and begins looking for a way to the Clore gallery. I pause the sound artwork and disengage from the performance. I have to walk outside to an alternative entrance and restart the guide, I’ve lost my place and I rewind it and try to re-orientate myself, a certain amount of the enchantment has been lost and it takes some time for my imagination to bring me back into the performance and engage with it again.

The problems I experienced in finding the Clore gallery are important considerations in creating these forms of ambulatory experiences. First and foremost the alternative audio guides must guide the participant around the gallery using pre-recorded locational directions through a one-way listening device. Tolmie et al (2012) discuss the implications of instruction for ambulatory experiences using ever more pervasive mobile technologies. They determine that instructions have four different levels:

1. “Location – attempting to get people to go to specific places

2. Sequence – attempting to get people to do things in a particular order

3. Comportment – attempting to get people to act and behave in certain ways

4. How they relate to the experience – attempting to get people to engage with it in certain ways and experience certain kinds of tensions and moods” (Tolmie, et al., 2012, p. 6).

Each instruction level interacts with the ones preceding it, the baseline requirement being that the participant reaches each location as and when expected otherwise the next levels of instruction that improve engagement with the experience cannot occur. To reach the Clore gallery meant I had to interpret the instructions as best I could and re-order the process, it involved my personal initiative and compliance with the soundwalk. By producing performance art without the author present to repair anything out of the ordinary such as building works presents a risk, as you are totally reliant on the participant solving their own problems, if they cannot then they may give up and end the experience early. There is a rich seam of instructions flowing through a ‘thin channel’ (Tolmie, et al., 2012), in this case the pre-recorded tour on a phone offers little room for manoeuvre when the unexpected occurs. The hope is that the participant can interpret instructions and manage an effective mutual performance of the soundwalk “in relation to what they understand this particular experience to be about” (Tolmie, et al., 2012, p. 6).

“What’s the worst that can happen if I listen to my inner voice? What happened to that wooden puppet Pinocchio when he listened to his conscience? He became real” (Biswas, 2012) [set to sounds of crickets].

The above quotation is where I begin the guide again, this is the second time (the first being the Jiminy Cricket quote earlier) where I am encouraged to question myself rather than just listen. It is an encouragement to think about my place, my personal reality, am I listening to my conscience? This quotation also serves to focus my mind again by reminding me of previous moments in the tour.

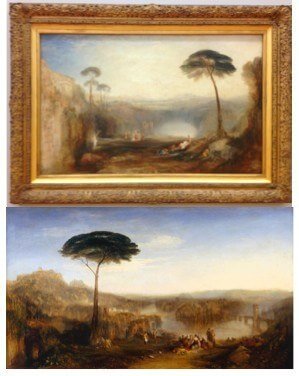

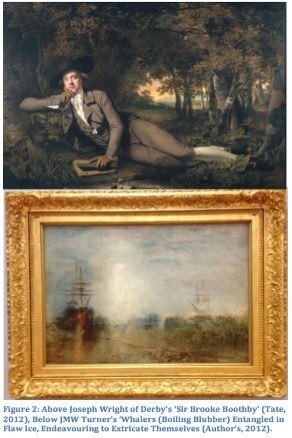

It is in the Clore gallery that I am first directed to a painting (figure 3), this is what I expect with a traditional audio guide. I sit on a bench in front of it while I am told about the painting, there’s a staff member in the corner of the room and he is looking at me. I wonder if he knows what I am doing and if he does what does he think about it. An aspect of these sound artworks is that they can be a permanent protest instillation inside the gallery, subverting the space and complicating BP’s relationship with the Tate. They are an individual act of protest and there is nothing the Tate or BP can do about it. The staff member cannot know for sure what I am doing but he may have seen many more people with headphones walk the same route as I. It is now, thinking this that I suddenly become aware of the security cameras. I’ve developed a sense of paranoia. Are they watching me? They must have noticed me when I sat on the floor in the rotunda listening to the rumble of the earth. Surely that was a giveaway of my true purpose of being here in the Tate, protesting against the Tate. This paranoia sends me further into the experience, the emotions are exposing my inner self and making me believe.

The voice tells me I am facing 345oNNW and if “I look through the painting and listen to what’s hidden from my eyes, I can hear the waves of structures rising. This is Clare, 1500 miles from central London in the cold North Sea” (Biswas, 2012). This begins the next movement of the soundwalk, surrounded by industrial oil rig sounds I am told this is BP’s oil rig near the Shetland islands. The imagery and metaphor used here is far from subtle – “giant iron butterflies sucking black nectar for a brief day of flight” (Biswas, 2012) – yet as a passage of prose it is rich and engrossing. The following description of the rise and fall of the whaling industry is an obvious metaphor for the oil industry and is very different from the surreal swampy sounds and imagery from the beginning of the tour. Sitting on the bench, solely listening to this intensely descriptive section, gives me an opportunity for my thoughts to mingle with the audio tour’s dialogue. In hindsight, it is an extremely powerful section. The discussion of the whaling industry makes you begin to think about how vast industries and structures change over time. It is the first point on the tour when I begin to question the BP relationship.

My next instruction is to look to my right towards a painting of a reclining male (figure 4). It is not there; instead I see a picture of boats. Immediately my mind jumps to sabotage of the tours by the Tate gallery. They’ve moved the paintings! I then get up to look at the painting I’ve been staring at the last five minutes, that’s a different painting as well. I was meant to be viewing ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’ but instead it was ‘The Golden Bough’ (figure 3), they do in fact look similar. I realise the tour is still playing and I’ve missed what was being said. I pause it as I walk over to the space where I was expecting ‘Sir Brooke Boothby’. He has been replaced by another of JMW Turner’s paintings entitled ‘Whalers (Boiling Blubber) Entangled in Flaw Ice, Endeavouring to Extricate Themselves’ (figure 4). I try to stifle a laugh; you’re not meant to laugh in galleries. I laugh, I’m not meant to be doing this audio tour either. I am almost in shock, if my thoughts of sabotage were right how fantastic is this replacement painting after my past five minutes have been spent likening BP to a messy and disreputable whaling industry.

Platform’s audio guides are situated pieces of performance art. They are designed to interpret a place. In this case the paintings are a major part of the place yet Platform have no control over what paintings are displayed. Already paintings have moved or disappeared so for longevity of the audio guides they need to be designed to still work within a changing space. Indeed on a future visit to Tate Britain building work stopped me from entering a room that was a central part of the Panaudicon guide. Biswas (Resonance, 2012) states that his soundwalk is designed more to interact with the gallery itself rather than what is inside it. This means that changing displays should not impact the effect of his tour too much. Actually it may improve it by developing a tension between the Tate and the participant as they wonder what has happened to the paintings like I did. When I was home I also found myself looking up the paintings that were meant to be there and emailing the gallery to find out where they had gone; the answer was disappointingly passive but the whole process had resulted in further action by me after the tours had ended. Performance art often needs to be designed with flexibility in mind so that it can react to changes in space and indeed to different participants who may enact the performance with small variations.

I begin the tour again and am directed to a new part of the gallery called ‘Colour and Line Turner’s Experiments’. Here I sit at a desk with a sheet of paper intended to allow me to imitate some of JMW Turner’s famous works, except, my direction is to close my eyes and draw whatever comes to me as I listen to a section on the destructive Alberta Tar Sands, replete with birdsong, tribal fires and Ansuman’s hypnotic voice and characteristic prose. When I am done the female voice tells me that I can do what I want with my resultant picture of pristine boreal forest, “it is up to you to decide how precious it is” (Biswas, 2012). There are more and more references to me, my role and my purpose.

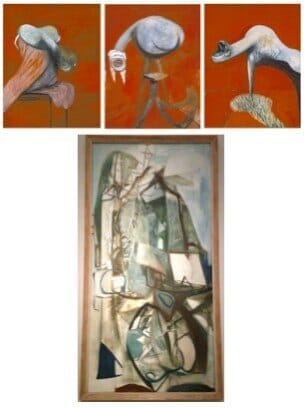

As I leave the romantics exhibition I am led towards Francis Bacon’s ‘Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion’ (figure 5), it is on the other side of the gallery so I listen as I walk. During this walk the tour moves towards a more direct dialogue on BP and its activities, with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the new Mad Dog oilfield taking centre stage.

I hear BP’s representatives sounded as snarling dogs whilst standing in front of Peter Lanyon’s ‘Porthleven’ instead of what was meant to be Francis Bacon’s painting (figure 5). The grotesque figures in Francis Bacon’s work whilst listening to the snarling dogs and the narrator discuss BP’s current oilfields would have worked well, however with the painting replaced I feel slightly lost and uncomfortable in the space, not knowing what to look at, and again wondering why the painting has been changed.

As I back away from the painting the dialogue becomes much more didactic, we are coming to the crux of the soundwalk. It explicitly and critically states why BP wants to sponsor the arts. I then receive the call to action from my ‘conscience’:

“If I am not to be a puppet, a robot, an automaton, a sleepwalker then I must make a conscious choice. Surrounded by wealth and prosperity I must deliberately choose what is good” (Biswas, 2012).

After the surreal, imaginative nature of the tour so far, with small pressure on my personal role in the issue, this sudden shift in tone and direct dialogue is striking and effective. Though the dialogue is direct, it is a call to think differently there is no determination to act in certain way (though it is obvious what they would prefer me to think) it is merely to be aware of and to listen to your conscience. This is made obvious as I am directed to stand in front of figure 6 ‘The awakening conscience’ by William Holman Hunt. I am left in a meditative mood, contemplating what I have just experienced standing in front of a painting depicting a woman whose conscience has been awakened and is represented by an idyllic English summer garden whilst listening to a soundscape of birdsong and summer sounds.

This 5 minutes in front of the painting (figure 6), left with my own thoughts, finds me reflecting on all I have just been exposed to. Rather than thinking explicitly about BP’s sponsorship of the arts, though that is very much in the forefront of my mind, I find myself thinking about how I am feeling, about my emotional response because surprisingly for me, something has lodged within me. A deep feeling, a seed of thought predicated in this idea of thinking about things differently and realising my own human agency. It is almost like my memory of this experience could be the catalyst for a form of action in the future, though I do not yet know what or when that will be. But I know that when the time comes I will be able to call on this sensual emotive experience to motivate me. It feels powerful and free.

The feeling I am left with is an emotional, sensuous seed; it is where art (especially participatory performance art) can make a big difference in sustainability. There are two differing forms of activism on display in the audio tours. Firstly from the creators of the audio tours there is the primary goal of ending the relationship between BP and Tate. The audio tours are one part of a wider campaign and their purpose is to spread the message through a different media form and entice individuals to further action directly related to the sponsorship issue, be this through attending meetings, taking part in other actions, sending messages, speaking to friends or signing petitions. However there is also a secondary form of activism, one that does not have a defined outcome and may not benefit Platform’s primary goal but arguably is far more powerful.

It is a concept that Heim (2005) calls ‘Slow Activism’. It was earlier discussed that art in sustainability is about changing cultural beliefs and encouraging transformative behaviour. Slow activism comes from the imaginative spaces that performance art can create, the spaces in which alternate realities can be imagined and rehearsed.

“Social practice events are providing contexts and places in which people can be listened to…places which are aesthetically and ethically coloured but not determined…These works create the conditions in which there is the potential to reason together about human actions within an unpredictable, uncertain world…occasions in which an altered capacity for responsiveness…can be undergone and embodied, and necessary rehearsals. They are experiences which make further experience possible” (Heim, 2005, p. 214).

Slow activism welcomes art’s determination to be open to any result. The artwork steers the conversation to certain areas but cannot force it to a predetermined point. “The activist potential develops in the time it takes to speak about something and for it to be ‘listened’ into existence. This involves not only the matter conversed, but the subjectivities engaged, which are, in the action, opened to change. It is improvisatory, slow activism” (Heim, 2005, p. 204). Activist potential has to be ‘listened’ into existence and that is the key; the participant is the key factor in determining the result, it is only from that individual that an activist potential can come into existence and all the complexities of being a human and the milieu that surrounds that person will influence the experience of the participant.

The slow activist potential of PLATFORM’s alternative audio tours comes from creating a sensuous, aesthetic and ethical experience that is at once enjoyable and informative. The arguments are compelling in that they are not forceful and didactic but enlivening the individual, making them aware of their place in the world, their sub-conscious feelings and their potential to influence; to break through the linear power structures and recognise complexity in the world. The aim is for empowerment by awakening the ‘aesthetic being’. These are emotional feelings that can be stored within and used to cultivate other experiences and to see the world in a different way, in a more questioning way. It seems that rather than slow activism this is prolonged activism. The audio tour experience lays an activist seed within the participant that can then grow depending on the future experiences of the participant. Kagan (2012, p. 37) concurs, stating “rather than trying to change reality heroically with big and salient actions and with abrupt events, we should rather explore the subtle propensity of situations, and induce changes by finding moments of inflections of propensities: In other words, moments of possible shifts of inclinations into other directions.”

REFERENCES:

Bacon, F (1944) Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion Tate Britain, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/bacon-three-studies-for-figures-at-the-base-of-a-crucifixion-n06171

Bello, P. D., & Koureas, G. (2010). Art, History and the Senses. Farnham: Ashgate.

Beuys, J (date unknown) Lightning with Stag in its Glare Tate Modern, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/beuys-lightning-with-stag-in-its-glare-l02180

Biswas, A. (2012). Panaudicon (Tate Britain alternative audio guide). (A. Biswas, Performer) PLATFORM, London.

Butler, T. (2006). A walk of art: the potential of the sound walk as practice in cultural geography. Social & Cultural Geography , 7 (6), 889-908.

Carruthers, V. (2011). Between Sound and Silence: John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and the Sculptures of Dorothea Tanning. In P. D. Bello, & G. Koureas, Art, History and the Senses (pp. 97-116). Farnham: Ashgate.

Certeau, M. d. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Code, L. (1991). What Can She Know? Feminist Theory and the Construction of Knowledge. Ithaca: Cornell.

Crang, M., & Cook, I. (2007). Doing Ethnographies. London: SAGE.

Denzin, N. (2003). A call to Performance. Symbolic Interaction , 26 (1), 187-207.

ecoartscotland. (2011, 03 28). Art and Sustainability. Retrieved 08 21, 2012, from eco/art/scot/land: a Platform for research and practice: https://ecoartscotland.net/2011/03/28/art-and-sustainability/

Ellsworth, E. (2005). Places of learning: Media, architecture and pedagogy. New York: Routledge.

England, P., & Welton, J. (2012, 06 22). Tate Modern Alternative Audio Guide. PLATFORM, London.

England, P., Biswas, A., & Suarez, I. (2012, 03 22). Resonance FM – Artist Interviews. (K. Smith, & M. Evans, Interviewers)

Fuller, M. (2008). Art Methodologies in Media Ecology. In S. O’Sullivan, & S. Zepke, Deleuze, Guattari and the production of the new (pp. 45-55). London: Continuum.

Gobo, G. (2008). Doing Ethnography. London: SAGE.

Gulati, D. (2012, 04 26). HBR Blog Network. Retrieved 05 2, 2012, from Harvard Business Review: https://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2012/04/stop_documenting_start_experienc.html?awid=7637955932758556576-3271

Heim, W. (2005). Navigating Voices. In G. Giannachi, & N. Stewart, Performing Nature: explorations in ecology and the arts. Bern: Peter Lang.

Heim, W. (2003). Slow activism: homelands, love and the lightbulb. The Sociological Review , 183-202.

Hunt, WH (1853) The Awakening Conscience Tate Britain, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hunt-the-awakening-conscience-t02075

Kagan, S. (2012). Toward Global Environ(mental) Change: Transformative Art and Cultures of Sustainability. Heinrich Boll Stiftung Ecology , 20, pp. 1-44.

Kagan, S., & Kirchberg, V. (2008). Sustainability: a new frontier for the arts and cultures. Frankfurt: VAS.

Kelsall, K. (2012, 05 15). Tate Soundscape Cleaned Up. Retrieved 07 24, 2012, from Dont Panic: https://www.dontpaniconline.com/magazine/radar/tate-soundscape-hijacked

Klink, I. (2010, 06 28). License to Spill. London: Liberate Tate.

Kounellis, J (1979) Untitled 1979 Tate Modern, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/kounellis-untitled-t03796

KulturKontakt. (2009). Interview with Hildergard Kurt: Art as a Sensitive Seismograph of Humanity’s Crisis. KulturKontakt , 9-13.

Kurt, H. (2006). Art and Sustainability: a Challenging but Promising Relation. Caderno Videobrasil 02 , 134-143.

Lanyon, P (1951) Porthleven Tate Britain, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lanyon-porthleven-n06151

Lehtonen, M. (2004). The environmental-social interface of sustainable development: capabilities, social capital, institutions. Ecological Economics , 49, 199-214.

Leviseur, E. (1997). Can Social Sculpture Be Taught? In A. Collaboration, Social Sculpture Colloquium (pp. 62-63). Glasgow: The Social Sculpture Forum.

Liberate Tate. (2011, 04 05). Alternative Tate Audio Tour: EXTENDED DEADLINE. Retrieved 07 11, 2012, from Liberate Tate blog: https://liberatetate.wordpress.com/2011/04/05/alternative-tate-audio-tour-extended-deadline/

Merz, M (1966) Untitled (Living Sculpture) Tate Modern, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/merz-untitled-living-sculpture-t12950

McCartney, A. (2005). Performing Soundwalks. In G. Giannachi, & N. Stewart, Performing Nature: explorations in ecology and the arts (pp. 217-233). Bern: Peter Lang.

Mesch, C. (2007). Institutionalizing Social Sculpture. In C. Mesch, & V. Michely, Joseph Beuys: The Reader (pp. 198-217). London: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd.

PLATFORM. (1997). PLATFORM. In A. Collaboration, Social Sculpture Colloquium (pp. 102-104). Glasgow: The Social Sculpture Forum.

PLATFORM. (2012). Who We Are. Retrieved 08 14, 2012, from PLATFORM LONDON: https://Platformlondon.org/about-us/

PLATFORM(a). (2012). Tate-a-Tate. Retrieved 07 31, 2012, from Tate-a-Tate: https://tateatate.org/index.html

Quaintance, M. (2012, 04 1). Morgan Quaintance. Retrieved 08 03, 2012, from Liberate Tate and Platform: Tate a Tate: https://morganquaintance.com/2012/04/01/liberate-tate-and-Platform-tate-a-tate/

Ratner, B. D. (2004). “Sustainability” as a Dialogue of Values: Challenges to the Sociology of Development. Sociological Inquiry , 74 (1), 50-69.

Sacks, S. (2007, April). Debates and Discussions. Retrieved 08 02, 2012, from Exchange Values: https://www.exchange-values.org/

Sacks, S. (2012). Performing an Aesthetics of Interconnectedness. Retrieved 08 02, 2012, from Green Museum: https://greenmuseum.org/c/enterchange/artists/sacks/

Sandlin, J., & Callahan, J. (2009). Deviance, Dissonance, and Détournement. Journal of Consumer Culture: culture jammers’ use of emotion in consumer resistance , 9, 79-115.

Sandlin, J., & Milam, J. (2008). ‘Mixing Pop (Culture) and Politics’: Cultural Resistance, Culture Jamming, and Anti-Consumption Activism as Critical Public Pedagogy. Curriculum Inquiry , 38 (3), 323-350.

SOUNDWALK. (2012). About. Retrieved 08 16, 2012, from SOUNDWALK: https://www.soundwalk.com/#/ABOUT/

Sowula, T. (2012, 04 06). Free Weekend? Try the Tate a Tate Guerilla Audio Tour. Retrieved 08 04, 2012, from The Kentish Towner: https://www.kentishtowner.co.uk/2012/04/06/free-weekend-tate-a-tate-guerrilla-audio-tour/

Spry, T. (2001). Performing Autoethnography: An Embodied Methodological Praxis. Qualitative Inquiry , 7 (6), 706-732.

Tate á Tate (2012) radio programme, Resonance FM, United Kingdom, https://soundcloud.com/Platformlondon-1/tate-tate-resonance-fm-radio

Tolmie, P., Benford, S., Flintham, M., Brundell, P., Adams, M., Tandavantij, N., et al. (2012). “Act Natural”: Instructions, Compliance and Accountability in Ambulatory Experiences. ACM .

Turner, JMW (1832) Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage Tate Britain, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-childe-harolds-pilgrimage-italy-n00516

Turner, JMW (1834) The Golden Bough Tate Britain, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-the-golden-bough-n00371/text-catalogue-entry

Turner, JMW (1846) Whalers (Boiling Blubber) Entangled in Flaw Ice, Endeavouring to Extricate Themselves Tate Britain, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-whalers-boiling-blubber-entangled-in-flaw-ice-endeavouring-to-extricate-themselves-n00547/text-catalogue-entry

Wright of Derby, J (1781) Sir Brooke Boothby Tate Britain, London, viewed 22 June 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/wright-sir-brooke-boothby-n04132