Guest blog post by Dr Alana Jelinek

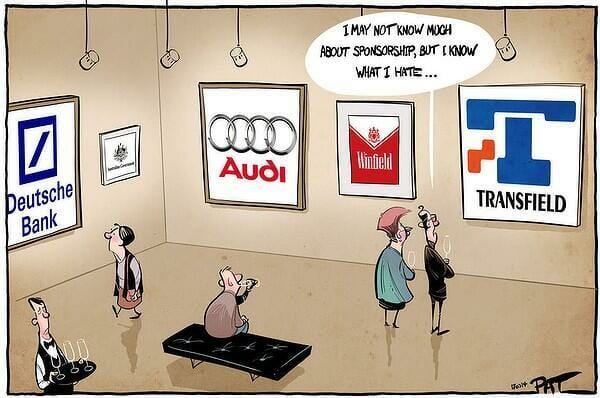

I have argued in the past that there are inherent problems with contemporary public-private funding models invented with the New Labour government and made very prescriptive since the year 2000 across subsequent governments of all hues. We can see just how prescriptive is its potential in the current Sydney Biennial furore over Transfield sponsorship and the response of the Australian government (and Murdoch press) to it. In short, the threat from Arts Minister Geogre Brandis is that if an artist or organisation refuses the private money, they are no longer eligible for the public. As it happens, there is also DCMS policy in the UK stating overtly in many of the contracts with nationally and internationally important museums and galleries that a certain percentage of income must be achieved through sponsorship.

The public-private funding model fosters not the philanthropic gestures that rhetoric around the model implies, nor does the public-private model serve as a continuation of previous governments’ arm’s length model of support for the arts. Instead contemporary forms of public-private sponsorship of the arts must be understood as the opportunity for strategic marketing campaigns for those types of corporation in need of the cultural capital of highly prestigious internationally-regarded arts venues and events.

In general, there are two sorts of companies that get involved with arts sponsorship as marketing strategy. The first are the banks and other parts of the financial industry, marketing their share value to other executives as the affluent consumers of nationally and internationally sanctioned art, thus indicating their blue chip credentials. The second are those who have ethical and ecological skeletons in their closets, where arts sponsorship is a major plank of a ‘good corporate citizenship’ agenda. Usually it is mining and oil companies that fall into this category, but in the case of Australia and the Sydney Biennial, the usual suspects (Rio Tinto, BHP, BP, Shell to name but a few of the latter type) are joined by the benign-sounding Transfield corporation.

So who are Transfield? Briefly, you would think from a quick scan of their own website that they are a community-focused charity-like organisation. What is obscured in their website is their activities in maintaining off-shore detention centres, where those seeking asylum or immigrant status to Australia are held and brutally treated across sites in Papua New Guinea and the Pacific island of Nauru. G4S is another company involved in this dubiously-legal practice initiated by the current very right-wing Australian government. There are many issues in Australia today to exercise those artists and others who uphold the value of human rights, biodiversity or sustainability (see, as one example), but the final straw that has inspired artists to act outside market norms and actually put their careers on the line, at least momentarily, is these detention centres and Transfield’s connection to the Sydney Biennial.

I will quote from Transfield’s website to explain the connection: ‘The Biennale of Sydney, the international contemporary art event, was established by Transfield Holdings in 1973. Transfield Holdings has remained its founding partner since that time. Last year the event celebrated its 40th anniversary. The Biennale of Sydney does not have any direct relationship with the public company Transfield Services – it is the private company, Transfield Holdings that has the 40-year relationship.’

On the 19 February 2014 a group of artists wrote an open letter to the Board of Directors of the Sydney Biennial refusing to participate given the connection (albeit symbolic) of Transfield to the biennial. The signatories are Gabrielle de Vietri, Bianca Hester, Charlie Sofo, Nathan Gray, Deborah Kelly, Matt Hinkley, Benjamin Armstrong, Libia Castro, Olafur Olafsson, Sasha Huber, Sonia Leber, David Chesworth, Daniel McKewen, Angelica Mesiti, Ahmet Ogut, Meric; Algun Ringborg, Joseph Griffiths, Sol Archer, Tamas Kaszas, Krisztina Erdei, Nathan Coley, Corin Sworn, Ross Manning, Martin Boyce, Callum Morton, Emily Roysdon, Søren Thilo Funder, and Mikhail Karikis. While some may have made a market calculation as to their future careers by boycotting, others have a history of ethical and political engagement. I applaud their gesture. There are many more artists who continue to support corrupt and dehumanising regimes (albeit symbolically) by lending their cultural capital through internationally and nationally sanctioned art venues and events. It is an important moment when artists have the vision to understand how our actions serve to maintain, or otherwise, the regimes in which we operate and when some artists have the moral courage to act. This is extremely pleasing.

Whether it is a market calculation (the artists can’t afford to be seen as siding with Transfield or the Australian government) or an ethical-political one, what is so important about this group of artists at this moment in time is that they have made a calculation that defies the current norms of the artworld; the norms that make it ok to show artwork and lend our substantial cultural capital no matter who pays for it and no matter what despotic tyrant is at the helm. Understanding that we are constitutive of the worlds, and artworlds, in which we live is the first and most important intellectual leap that we each have to take. The next step is to decide how to act once we have accepted that every action we choose to perform or otherwise is constitutive of our world.

Dr Alana Jelinek is an Australian artist and academic who worked in the past with Platform on the C Words season curated at the Arnolfini gallery in Bristol. She is also the author of This is Not Art: Activism and Other ‘not-art’