This piece (originally titled “From oil to art, liberating culture”) is reprinted from The New Home Front II: Policies for Ecological, Social and Economic Renewal that was launched by Caroline Lucas MP in September 2012, outlining a range of policy proposals designed to set the UK on a path to a clean, green future. Since the piece was written, Osborne has announced even more tax breaks for the oil and gas industry, while just this week Arts Council England announced cuts to its own operations.

This piece (originally titled “From oil to art, liberating culture”) is reprinted from The New Home Front II: Policies for Ecological, Social and Economic Renewal that was launched by Caroline Lucas MP in September 2012, outlining a range of policy proposals designed to set the UK on a path to a clean, green future. Since the piece was written, Osborne has announced even more tax breaks for the oil and gas industry, while just this week Arts Council England announced cuts to its own operations.

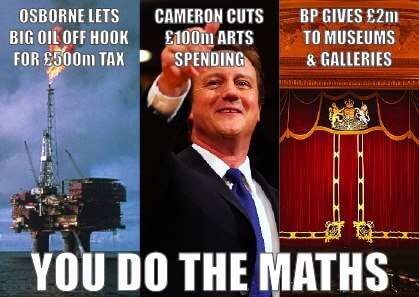

The UK arts sector, like many other vital public services, has been a victim of the draconian cuts imposed by the coalition government. In March 2011, a quarter of the theatres, galleries, and orchestras receiving funding from Arts Council England lost all their government grants in cuts amounting to £100 million.

Many small, community-based or radical arts practitioners have little recourse in the face of these funding cuts. More high-profile arts institutions not only continue to receive public money, they also supplement it through corporate sponsorship. Oil companies have provided the most high profile and the most controversial of these deals. At the end of 2011, BP announced a £10 million deal for four arts institutions, including Tate, over five years.

Despite the sustained criticism of the cheap greenwashing provided to oil companies like BP, including a series of dramatic performance-interventions by groups like Liberate Tate in the gallery spaces, some art commentators are adamant that arts cuts means that now is not the time to discuss the ethics of corporate sponsorship. Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones went as far to suggest that the arts should take ‘money from Satan himself’ if it means that museums stay ‘strong and free’.

But is increasing the corporate sponsorship of cultural institutions really keeping them strong and free? Capitalist Realism author Mark Fisher in a recent critique of the corporatisation of the Olympics wrote:

The point of capital’s sponsorship of cultural and sporting events is not only the banal one of accruing brand awareness. Its more important function is to make it seem that capital’s involvement is a precondition for culture as such.

Would our cultural institutions feel the need to see private capital as a precondition for their existence if they were properly funded from public coffers that in turn were properly resourced from a more appropriate level of corporate taxation? In July 2012, Chancellor Osborne announced a tax break of £500 million to oil and gas companies operating in the North Sea. The size of this public subsidy dwarfs not just the paltry amounts that BP passes off as cultural philanthropy, but also the cuts in public spending to the cultural sector as a whole.

State funding for the Arts is not without problems of its own – but the fundamental difference is that there is a semblance of accountability and transparency that makes democratic intervention to address those problems possible. Tate, as a public body, won’t even reveal how much money it is getting from BP.

The Arts have a vital role to play in engaging with the most critical issues of our time, from the threat of climate change, to the extent of corporate power. We need to ensure that the cultural sector is publicly funded and independent so that can do this free from the constraints of pernicious parameters imposed directly or indirectly by corporate sponsors.

You can read a briefing that Platform published with Greenpeace UK in 2011 called Death knell or crying wolf? that compares how UK’s tax regime for the oil and gas industry compares with that of other countries.