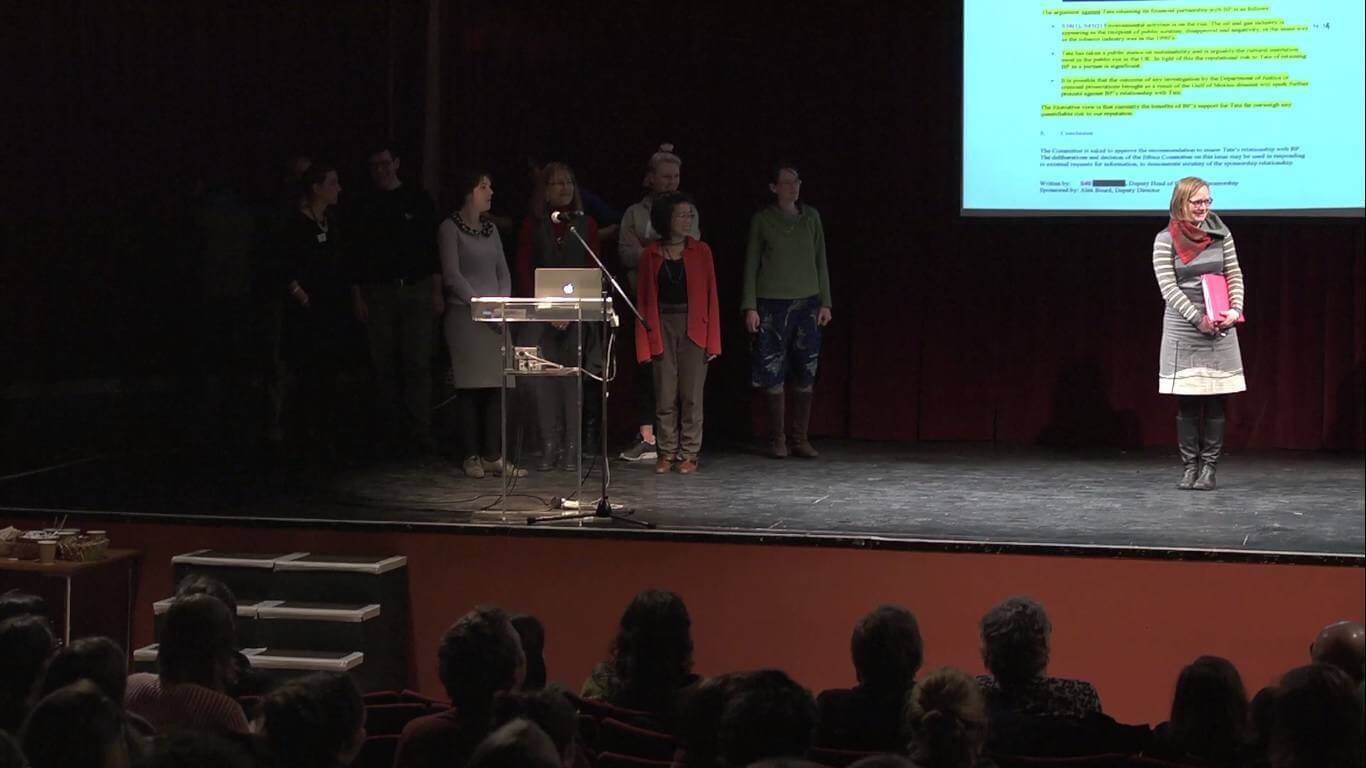

Take The Money And Run? was an event about ethics, funding and art that took place at Toynbee Studios, London on January 29, 2015.

Attended by over 200 people, it was a day of presentations and discussion hosted by three organisations, Live Art Development Agency, Artsadmin, Home Live Art and produced in collaboration with Platform.

We commissioned Mary Paterson to create a written response to the event and Ana Matos to create a short film of the day. This documentation represents the culmination of our collective work on ethical funding issues over the previous two years (supported by Arts Council England’s Catalyst programme) and we are delighted to make it widely available to everyone who is engaged with these issues.

See the 40-minute video documentary here and Mary Paterson’s response below.

Introduction

by the Live Art Development Agency, Home Live Art and Artsadmin

Take the Money and Run? was an event about ethics, funding and art, which took place in London on January 29, 2015. It was a day of presentations and discussion hosted by our three arts organisations and produced in collaboration with Platform.

In many ways, the event represented the culmination of our collective work on ethical funding issues over the previous two years, which was supported by Arts Council England’s Catalyst programme. Catalyst is designed to enhance organisations’ fundraising capacity, and for our three organisations questions of ethical funding were central to our research. Three issues provided an important context for our Catalyst programme and shaped that research:

First, we work with Live Art and performance practices which can be subversive and may represent a number of challenges to conventional ideas of sponsorship and philanthropy. As part of our fundraising research we were driven by a goal to ensure that our fundraising approaches would be aligned with our missions and values – could our fundraising be informed by longstanding, tried and tested fundraising principles, but still be true to our radical programmes and experimental ways of working?

Secondly, back in 2012, Home Live Art (HLA) was invited by the British Museum’s Education and Learning Department to create an event as part of the celebrations around their ‘Book Of The Dead’ exhibition, which was sponsored by BP. Although HLA‘s event was not part of BP’s sponsorship package, their participation in the exhibition caused concern amongst some artists and highlighted the difficult area of “being associated with” a sponsor through association or by default that you do not wish to endorse. The key issue for HLA and for Artsadmin (AA) and LADA was that we clearly needed policies or guidelines to ensure that situations like this don’t arise in the first place, or if they do, ensure we have a procedure that will guide our response.

Lastly, in 2012 LADA worked with Jane Trowell of Platform on a Study Room Guide on ethical funding, “Take the money and run? Some positions on ethics, business sponsorship and making art”, and on a reading group to discuss issues raised by the Guide. The Guide is available as a free PDF download, and was also produced, in response to popular demand, as a booklet, now in its second printing.

Through our Catalyst funded research each organisation has significantly advanced its understanding of ethical funding issues, and has developed a policy, plan or guidelines. We continue to gain valuable new insights through dialogue and sharing with others, such as the Take the Money and Run? event.

The event came at an auspicious time. Over the last year there has been a groundswell of debate about the ethics of fundraising and growing dissent about the conflicts and contradictions between commerce and culture. More recently there has been a huge increase in media coverage of these issues, in particular oil sponsorship of the arts, in part responding to initiatives across the cultural sector and wider social movements. The day’s discussions reflected this sense of urgency and many of the complexities of these issues, and ended on a spirited note and with a sense that there is momentum, and that change is possible.

We invited the writer Mary Paterson, who also participated in Jane Trowell’s ethical funding reading group, to respond to the day’s presentations and discussions. We hope Mary’s writing, and other documentation from the event, will inform and encourage further action.

Take the Money and Run?

a response to an event about ethics, funding and art

by Mary Paterson

Who funds the arts, why does it matter, and what should we do about it? This was the ambitious remit of Take the money and run?, a day of presentations and discussion hosted by three arts organisations (Home Live Art, Artsadmin and the Live Art Development Agency) and produced in collaboration with Platform. Jane Trowell, from the artist-activist group Platform, facilitated the event.

The context, said the organisers, was the increasing pressure on artists and arts organisations to “seek support for their work from corporate sponsorship and individual philanthropy” – in other words, to renegotiate the relationships between culture, business and the state. As a result, “questions about cultural values, the ethics of fundraising, and who we are prepared to take money from are becoming more and more urgent.”

Arts funding shapes what kinds of art are produced, published and valued. It affects the actions of arts managers, artists and audiences, and it defines who can be an artist, arts worker or audience member in the first place. This means that to talk about arts funding, is to find yourself tangled in a web that includes the production and distribution of global wealth, as well as the meaning of art, and the experience of individual art encounters. No wonder, then, that most of the presenters inside Toynbee Studios (London) gave themselves a caveat – a variation of, “I’m not an expert, but…”

And yet, as the artist Harry Giles said, speaking from the floor: “It’s not about you.” The issues at stake in the ethics of arts funding are bigger than any individual, and critical to every person who takes an interest in culture.

Leaks and lines: the clear-cut case of oil sponsorship

If there is one subject that offers some respite, however, from the complexity and size of the larger debate, it is oil sponsorship of cultural institutions. Testament to the currency of this issue, TTMR? hosted three presentations from artists who are actively engaged in breaking down the relationship between art and oil: Mel Evans, author of the forthcoming book Artwash, and Glen Tarman and Jess Worth from the campaign groups Liberate Tate and BP or Not BP?, respectively.

If there is one subject that offers some respite, however, from the complexity and size of the larger debate, it is oil sponsorship of cultural institutions. Testament to the currency of this issue, TTMR? hosted three presentations from artists who are actively engaged in breaking down the relationship between art and oil: Mel Evans, author of the forthcoming book Artwash, and Glen Tarman and Jess Worth from the campaign groups Liberate Tate and BP or Not BP?, respectively.

Some of the UK’s most prestigious cultural organisations – including Tate, and the Science Museum and (formerly – we’ll come back to this later) the Royal Shakespeare Company – are sponsored by two of the world’s biggest oil producing companies – BP and Shell. The problem, say the activists, is that BP and Shell are responsible for ecological and human rights abuses on a massive scale. This, alone, makes it inappropriate for them to be associated with the giants of our national cultural heritage. But it gets worse. One frequently quoted BP memo describes cultural sponsorship as a route to gaining “the social licence to operate.” BP’s logo on Tate banners is designed, in other words, to dilute and distract from the real consequences of the company’s work. It is part of a dialogue, not with audiences and consumers, but with governments and influential individuals. This is high-status art being used to grease the wheels of a hidden discourse in trade deals and international access. In 2010, only months after the catastrophic oil spill at BP’s Deepwater Horizon base in the Gulf of Mexico, Tate held a party to celebrate 20 years of BP’s support.

Liberate Tate and BP or Not BP? are campaign groups set up by artists to confront individual cases of sponsorship. Their tactic is to turn the very asset the sponsors are trying to leverage – the power and status of art – against them, by using art as a form of protest. In 2010, Liberate Tate gate-crashed that celebratory party for BP, spilt 10 gallons of molasses on the floor and made a mess of clearing it up – just like the mess BP was making of the clear up in the Gulf of Mexico. In 2012, actors from BP or Not BP? stormed the stage of every RSC show in the season, and performed a Shakespearean soliloquy questioning the ethics of BP sponsorship.

Like all good works of art, these protests are effective and communicative. As such, they have the advantage of talking directly to the people that the sponsors ignore – the audience; they pierce the secretive world of corporate funding, and wrestle the debate away from money (how is this paid for?), back onto art (why does art matter?). The RSC speeches were greeted with applause – as much for their skill, I suspect, as for their content. And they were a success: since 2012, the RSC has not been sponsored by BP.

Evans, Tarman and Worth agree: oil companies are not only unwanted, they are also unnecessary. The amount of money they give in sponsorship is relatively small (0.5% of Tate’s annual budget, for example, is funded by BP). And there is a recent precedent, in the tobacco industry, to demonstrate how an entire sector can be shunned from cultural sponsorship, on the grounds of a black and white ethical decision.

The clarity of this argument owes a lot to the fact that it’s part of a global movement against unethical corporations. Artistic protests in the UK contribute to a virtuous circle that wears down the public profile of BP and Shell around the world. At the same time, British artists benefit from an international movement that establishes the case for prosecution. While arts funding is a thorny issue, said Jess Worth, this is clear cut. Here, between art and oil, is where we can draw a line.

Murky Waters: the ideologies of money

Anti-oil activists know how BP and Shell sponsor the arts, and they know why. But elsewhere, the relationships between the origins of money and the production of culture are not so easy to define, or to condemn.

At the start of TTMR?, the artist duo Ackroyd & Harvey described their encounter with Here Today, an exhibition held in London in 2014 to highlight the plight of endangered species. The subject matter of the show chimed with their work, and they accepted an invitation to participate; but over time the artists grew suspicious of the real intentions behind the project.

Here Today was sponsored by Baku Magazine, whose CEO was also one of the artists exhibiting. Further investigations revealed more links with the Azerbaijani government, which has a history of human rights abuses: a relationship which, in the artists’ words, “detonates” the values of the exhibition itself. And, mysteriously, the exhibition, which was held in a central London venue, received hardly any press. When Ackroyd & Harvey were asked to sell their work to the exhibition organisers (to be donated to a university), they said no, on the grounds that the relationship felt manipulative and unclear.

“Artistic integrity is not paramount,” said Heather Ackroyd, talking about an earlier confrontation with advertisers, “it is instinctive.” Likewise, the hidden agenda ofHere Today imposed itself on her artwork and compromised its meanings; or indeed, its ability to mean at all. Rachel Spence, arts writer for the Financial Times, said that art offers a “fantasy” world – a rich and necessary part of our psychic makeup, whose efficacy relies on its difference to the productive imperatives of everyday life. But how can we decide when the outside world is too close to the artwork? How do we know the difference between money that facilitates art to happen, and money that threatens its very existence? How far should artists investigate their funders’ histories? And who, in the midst of it all, can we trust?

Speaking later in the day, Judith Knight, Director of Artsadmin, said that she wants people to pay taxes and for funding to be fairly and widely distributed by the state. Amongst stories of disillusionment and protest, it is refreshing to think about a system we can fight for, as well as the mess we must fight against. A fair, publicly funded system also relies on a fair, democratic government, and Knight’s proposal is therefore not just for a better cultural ecology but also for a better society. As Spence pointed out, government spending on the arts (in the West) in the 1970s was flavoured by the Cold War: there is no money that comes without an ideology trailing behind.

In this light, the wider issue of ethical funding in the arts becomes more nuanced and introspective than issue-based protests need to be. Knight gave the example of the ‘What Next?’ movement – a series of meetings between people who care about the arts, which attempts to articulate and understand why art is important. This has to be the starting point for any serious conversation: before we can decide how to support culture, we must describe its place in the world.

Talking points: dialogue as culture

Crucially, ‘What Next?’ discussions are held between artists, arts workers and audiences – the people who make, programme and experience art; and not between governments, financiers and corporations – for whom art is not the purpose but one tactic of dialogue. ‘What Next?’ is a practice of art and politics that works on two levels: to debate the context in which art thrives, and to create a model for debate itself, based on democratic and participatory ideals.

In the 1990s, the festival organisation LIFT ran the ‘Business Arts Forum’ to foster dialogue between artists and businesses. The forum asked members to engage, personally, with the ethics at stake in both business and culture and, as Lucy Neal (one of LIFT’s founders) said from the floor, the discussions were open, frank and powerful enough to change people’s minds.

One of the results of LIFT’s Forum was that some (business) members decided to leave their jobs. They discovered that their personal ethics were at odds with their employers’. At TTMR?, one audience member said the same option is open to arts workers who disagree with their organisation’s ethical stance (although low wages in the cultural sector make it difficult to give up paid work). But whereas rows of people smiled at Neal’s observation, the idea of people quitting the arts for ethical reasons is less palatable.

Partly, this is because art functions as a transition between private and collective experience. Art, in Kantian terms at least, is how we know other people exist – not as cogs in a machine but as thoughtful, reflective beings. Art is both the profound recognition of people as individuals, and the insistence that we belong together. If a bank sacrifices its employees’ needs for the sake of money, its method is at least consistent with the ruthless pursuit of growth. If an art gallery does the same, it is making a mockery of its own reason for existing. (Nevertheless, this is exactly what the National Gallery and the Dulwich Picture Gallery are doing at the moment, said Clara Paillard from the Public and Commercial Services Union, in a tub thumping speech, which addressed, amongst other issues the use of zero-hours contracts.)

It is a hallmark of art, then, that artists and audiences should be able to influence their own culture and means of production, distribution and interpretation. Participation is the basis of an ethical relationship, not just between artists and funders, but between (artists and) everyone. The model for debate enacted by ‘What Next?’, is not just a way of arriving at a description of culture, but a good working description in its own right. And this, of course, is also the argument for public subsidy. Unlike private investment, public subsidy is (in theory at least) transparent and accountable. If you don’t think it works well, then it is possible (in theory at least) for members of society to make a change.

Visibility: ethical policies

While extended dialogue might be an ideal way of working, most artists who use money will, at some point, face a pragmatic decision about when and how to accept funding. Jane Trowell, from Platform, set an exercise in the afternoon session of TTMR?: she read out a list of brand names – Tesco? Smirnoff? Channel 4? – and asked audience members to make snap judgments about whether or not they would take the brand’s cash.

As well as a startling reminder of the power of brands, this game quickly visualised the differences between individuals, organisations and, sometimes, between artists and the audiences they are trying to reach. Richard Lee from Stagetext said that, confronted with the need to pursue funding for the first time, he has to balance his personal politics with the fact that many Stagetext users read The Daily Mail.

Earlier, Spence suggested that banks are ubiquitous funders of the arts because they have the most social capital to make up. Ironically, private investment offers an opportunity for organisations whose operations are most opposed to art and culture, to redeem themselves by borrowing some of art’s subtlety, its influence and its special status. How strange then, said James Marriott from Platform, that artists are in a position of supplication to donors. We should expect sponsors to be grateful for our support, not the other way round. We should expect to set the terms of our engagement, not be subject to the pseudo-morality of financial imperatives. Is it possible to imagine a world where Stagetext could approach The Daily Mail and ask the newspaper to change?

The Live Art Development Agency (LADA) has a sensitive approach, explained its co-director CJ Mitchell, aimed at articulating the organisation’s values and communicating with colleagues in the sector. LADA will work with Tate, for instance, on the condition that BP sponsorship is not associated with the collaboration, and that LADA’s position on this is communicated internally to senior Tate staff. This last point is crucial – a principled but non-confrontational act, which may make it possible for Tate staff to voice their own concerns. Similarly, the artist Kelli McCluskey from pvi collective, speaking over Skype, described the ‘ethical arts resource’ she is creating in Australia. It aims to help artists gather materials and evidence, in order to make better informed arguments for ethical relationships.

A Sea Change: framing the debate

The trigger for the ethical arts resource, explained McCluskey, was the link between the 2014 Sydney Biennial and the security firm that operates the Manus Island detention centre, a prison for asylum seekers off the Australian coast. Artists protesting this relationship also boycotted the Biennial, and continue to campaign against the automatic detention of asylum seekers. Their multi-layered response to the festival’s finance is, in effect, a decision about hierarchies of communication. Via boycott, the artists refuse a dialogue with funders; and via the resource, they foster dialogue between artists.

Fern Potter from Dance UK joined the discussion to say that, instead of boycotts, she prefers to engage with private investors, working closely to change them from within. And yet boycotts and protests are a kind of engagement, too. In fact, said Dave Beech, from the Freee Art Collective, any movement that tries to make private investment ‘better’ is also a movement to preserve the status quo. Rather than object to BP, for example, Beech would like to eradicate corporate sponsorship absolutely. In Marxist terms, he explained, his end goal is not social democratic reform, but a wholesale political revolution that attacks capitalism and its inherent patterns of exploitation.

In a way, artists who insist on dialogue and co-operation also make a case for revolution, albeit of a cultural and not a political kind. Prioritising the welfare of migrants over the career potential of a Biennial, for example, the Australian artists protesting in 2014 were enacting an alternative value system that places people over money.

Likewise, David Cross is both an artist who rejects the idea that we have to make pragmatic decisions about arts funding, and an academic campaigning within the University of the Arts, to divest the institution from fossil fuels. His approach is to combat the logic of fossil fuel investment, by replacing it with another kind of argument altogether. He showed us a detailed diagram of people’s motivating values and emotions – a colour wheel that moves from power and achievement, to universalism and benevolence. As individuals, Cross said, we swim between these feelings on a daily basis. But as employees and consumers – that is, as people subject to the structuring principles of finance – we are meant to act according to one idea at a time. This is how finance reduces our intricate individual lives to ‘human capital’, just as sponsorship diminishes cultural institutions to the ‘social licence to operate.’

What would happen, Cross asked, if these imperatives were reversed? If a multitude of shifting human values were imposed onto the simplistic value systems of capitalist society? This would not be a like for like replacement, of course, but an entirely new paradigm for knowledge, communication and meaning. What kinds of processes and practices would bring this new paradigm into being?

Swimming away: communities of disobedience

At one point, early on in TTMR?, the room felt close to despair. “Are we projecting evil onto an other?” asked an artist from the floor, as we all reflected on our smartphones and the real cost of our coffee. But (just like oil sponsorship) fatalism is neither useful nor necessary. “Politics,” said Beech, “is a practice.” If a boycott is a type of engagement, so David Cross’s call for a different frame of reference is the start of a conversation. Beech doesn’t think that single issue protests will deliver the revolution he’d like to see; but he supports them anyway, as a practice of community. It is the community of political activism that will, eventually, induce real change.

The question of community is the crux of the debate. As a way of recognising people, art is both the fuel and the product of community, and when artists say that funders negatively influence their work, they are really saying that funders don’t belong to the kind community of potential in which art can thrive. It is easy to agree with Liberate Tate that BP should not be allowed to rebrand the national collection of British Art, for instance. But nobody says Liberate Tate’s conceptual performances are ‘compromised’, because they respond to the pleas of people affected by oil spills and other aggressive business practices.

The difference, of course, is that when Liberate Tate brought a full sized wind turbine into Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, they were drawing poetic attention to the gallery’s competing commitments to sustainability and its sponsors, rather than telling people what to do. Performers carried the huge metal artefact across Millennium Bridge and into the museum’s cavernous space, where they encircled it and held hands, until security guards stopped them. This performance was the imposition of a community of art, activists and people into the heart of the Tate, to expose the simplistic and directed kinds of experience the space normally allows. It is worth noting that the only reason Liberate Tate exists is because of a spectacular misfire in Tate’s corporate message: Tarman went to a Tate workshop about radical art, where attendees were told they must not criticise the museum’s sponsors. But Tarman is an artist. He did not follow orders.

Survival: methodologies and practices

Take the money and run? was produced by three arts organisations working in consortium, as a result of funding through the Arts Council England’s ‘Catalyst’ programme. Catalyst, says ACE, is a “£100 million culture-sector-wide private giving investment scheme aimed at helping cultural organisations diversify their income streams and access more funding from private sources.”[1] As such, it is part of the current government’s ideological plan to encourage greater philanthropy and corporate sponsorship of the arts.

The symposium, then, was itself an object lesson in communities of complicity and resistance. TTMR? was both a direct outcome of the Catalyst funding stream, and an attempt to explore the meanings, consequences and alternatives to its approach. Its discussions about ethical funding were made possible by a state-sanctioned desire to encourage private investment; and they were also a form of resistance to this desire – resistance to private investment in particular, and resistance to the ideological impositions of funders in general.

This is how we all operate in the arts. Indeed, it’s how we all operate as individuals within globalised capitalism: we float inside systems we cannot escape, and with which we only partially agree. “Thank goodness,” said Heather Ackroyd, “we’re all educated in the school of hypocrisy.” I would put it like this: it is not just possible to occupy more than one ethical position at once. It is a matter of survival.

Perhaps, as David Cross suggests, it is even an asset. “Why should artists be the vanguard standing against unethical organisations?” asked the academic Jen Harvie, in provocation. Art is by no means the only part of society threatened by unethical governments, companies or individuals. But, if politics is a practice, then artists already have a head start in the methodology of resistance.

An ethical approach to funding is not (only) about drawing a line and taking a stand. Amongst all the tactics suggested at TTMR? – ranging from ‘use less money’, to ‘start a revolution’ – the common principles were dialogue and community. Like Dave Beech, you may not agree with everyone else’s agenda, but you can stand in solidarity with artists who want to explore change. Underlying all of this is a belief in the value of art as an activity that exceeds and escapes its own currency in any other value system. Art’s strength, its value and its ethics come down to this: an ability to be and do more than one thing at once – to recognise the necessity of hypocrisy, and to summon the imagination to occupy different points of view.

TAKE THE MONEY AND RUN? an event about ethics, funding and art took place on Thursday January 29, 2015, at Toynbee Studios, London.

The event was financially supported by Arts Council England through the Catalyst programme, and produced by Live Art Development Agency, Artsadmin, Home Live Art and Platform.

Further documentation:

The freesheet given out on the day can be downloaded here.

The above piece by Mary Paterson can be downloaded here.

Jane Trowell’s ‘Take the Money and Run? Some positions on ethics, business sponsorship and making art’ guide can be downloaded in PDF or purchased here.